The Jonga grinds to a halt just beyond a desolate village of brown and grey stone houses that is now a loading station for the Sikh Light Infantry.

Major Chiranjeet Singh Gill, a tall, strapping, handsome Sikh in full battle regalia, steps out purposefully, walks up to the Mahindra Commander, pulls the door open and jerks his head as if calling his troops to order.

“You shouldn’t be here, you know.” Behind him, the hillside to which the dirt road clings rolls on to a field of satin green millet and yellow mustard and then on to a gushing rivulet before the earth rises again in a barren, craggy hill. The major, arms akimbo, Ray-Ban glinting in the sun-washed valley, must be humoured.

“Neither should you.” Shock? Puzzlement? Just before it turns to anger, you explain: “You must have talked about it yourselves when you’re in the mess with friends. It is too beautiful to be a war.”

The lips twitch, then part in a smile. The tactic works and, in repartee, earns a quote I later pass off as my own. “That’s why it is a land worth fighting for.”

The major leaves with a word of caution — “Don’t stay here too long, the shelling gets really hot after 2pm” — and a request: “Please don’t identify names and formations in your report.”

He is off to a battery of artillery, the dust raised in the Jonga’s wake choking a soldier leading a mule train to two Shaktiman trucks with cartons of Amul milk in tetrapacks, jerry cans of kerosene, crates of eggs, tea and butter. These must be transported 8.5km further north on muleback to those who have laid siege to Tiger Hill.

It takes each soldier 40 minutes to the top of the first hill. “You will take about an hour without any load.” It’s a compliment, really, to lungs that have not yet acclimatised. And Tiger Hill?

“You can’t do it,” the soldier leading the mule train says. “Even we can’t do it all the way to the top. That’s for our betters.”

This is an infantry regiment experienced in high altitude but made up mostly of plains people. The ones who will lead the assault are born in climes that work lungs like giant bellows, mould sinewy muscles into tendons of steel. Some of that could be blown, torn, shattered by bullets, bombs, grenades hurled from nearly two-and-a-half dozen bunkers that were built by Indian troops along a flank with a 2.5km sharply-inclined ridge and 5,080m high.

The enemy, it is assumed, has occupied most of the bunkers and built some of its own just before the snows started melting. Indian bunkers facing the Pakistani side would not have been of any use to the intruders. So, though Indian bunkers were occupied by the infiltrators, new ones were also built.

Down here in this Mushkoh Valley village, though, as he picks out a list of supplies being despatched, the subedar is unmoved by the thok-pam of shells landing on the opposite hill. “These hills are soft. So the projectiles often get embedded and the noise is a little muted,” he says casually for someone heading for Tiger Hill. We reach a point when it must be asked how the enemy got up there before the army.

“What do we know? What must be done must be done. Maybe someone has blundered, maybe someone got cleverer.”

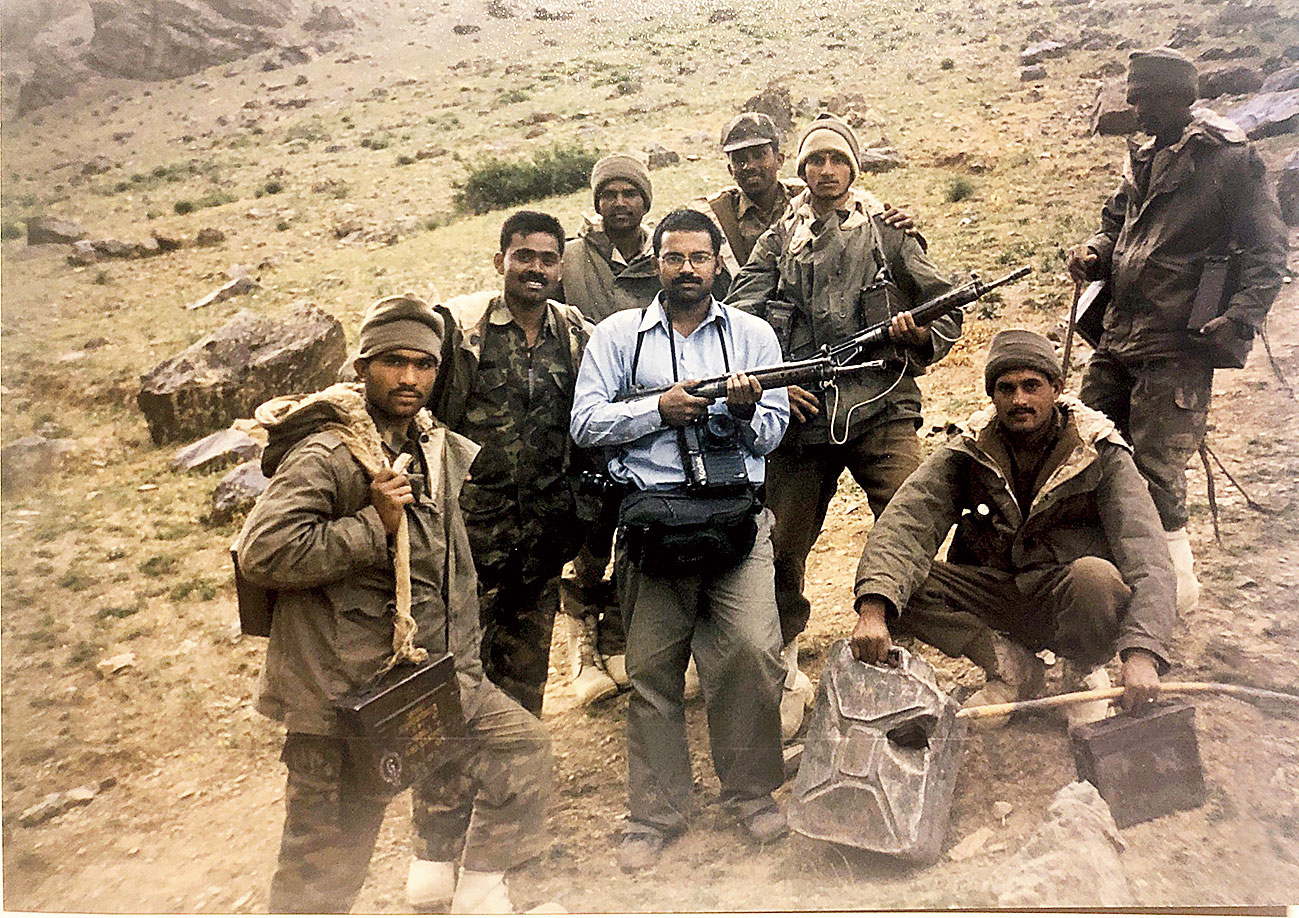

Sujan Dutta in Mushkoh

This story was first published in The Telegraph in 1999