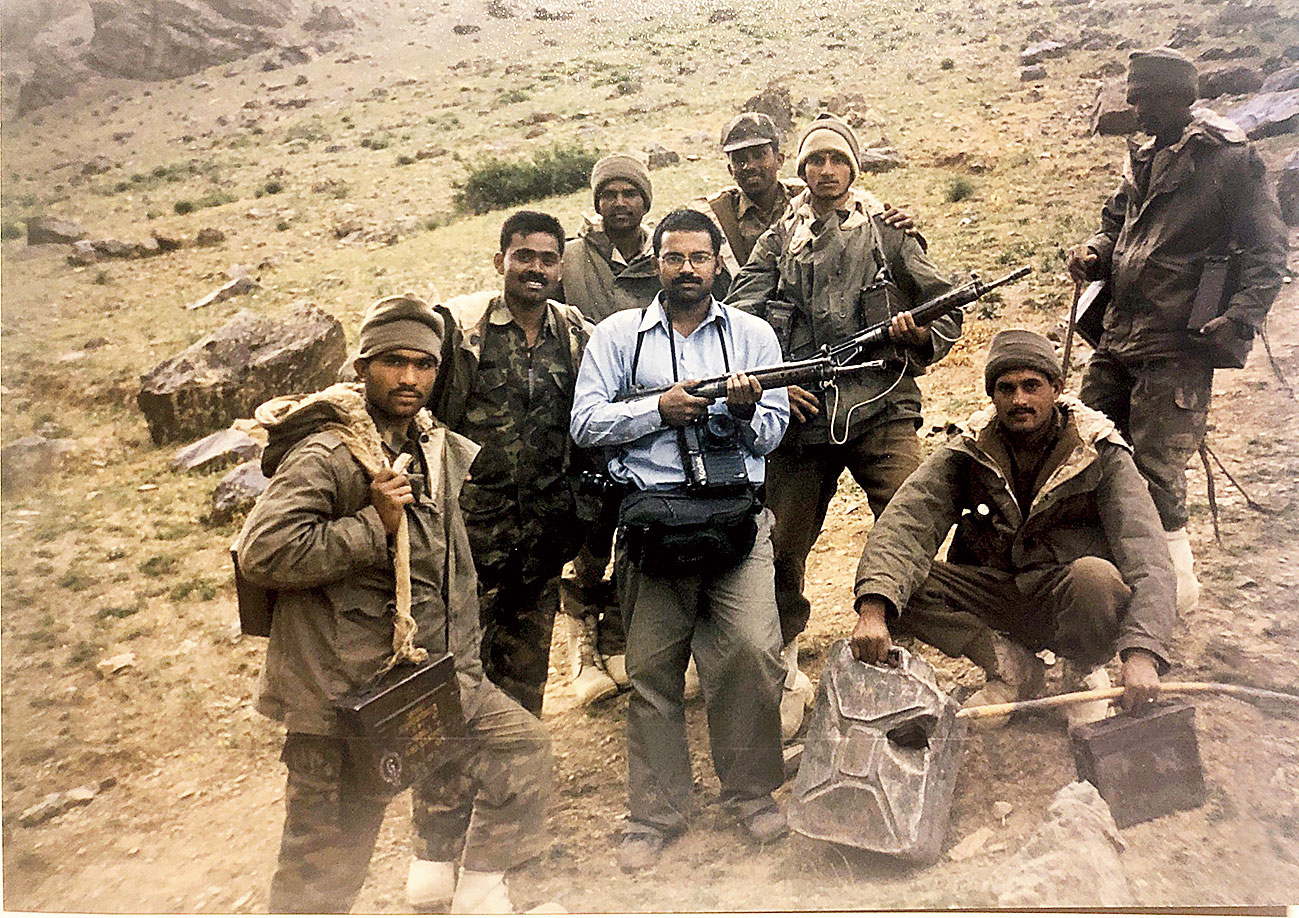

Yesterday’s report from the front came to you courtesy Associated Press (AP) photographer Saurabh Das. We had been watching the twilight assault on intruder positions around Peak 5140 from a little clearing in the Drass army camp — he through his fascinating arsenal of lenses, I through wondrous wide eyes.

Perilous though they are, Drass offers the best spectator seats on the high voltage battle for supremacy over snowy mountains that run along the troubled India-Pakistan frontier. Looking left to right from the concave, shelled-out centre of Drass, you can see the three heights that hold the key to security on National Highway 1A and to India’s territorial contiguity in upper Kashmir — Tiger Hill stands to the extreme left, still streaked with snow, then comes Peak 5140, a lofty grey mountain with broad flanks, and then, Tololing, a craggy peak with down to earth contours, the kind schoolchildren etch in their drawing books.

Tololing was already taken by Indian troops, Tiger Hill was awaiting a final push for conquest and 5140, at the centre of Drass’ panavision screen, was under fire.

Mortar strikes were ripping up its ridges with rapidfire ferocity and so many artillery shells were landing on the mountainhead, 5140 looked like a volcano spewing smoke, or, a demon being slowly put to death. Infantry contingents made noisy progress across the camp, arriving from battle or departing for action, and soldiers on camp skittered about to reach their bunkers before night descended. “The action will begin now,” one helmeted jawan said as he hurried down the road to his muddy haven-in-the-ground, “Get ready for the daily pounding.” But the attention last evening was already riveted on the drama on 5140.

It was dark all too soon and suddenly that other demon began to haunt us: deadline. The artillery fire was beginning to flash behind the smoke plumes on the mountain and embattled positions flickered with bursts of machinegun fire.

The recounting for the day was concluded on a laptop in a captain’s lamp-lit shed even as the fiery spectacle unfolded on the mountain. But for the relaying we had to be out again into the open of the night.

Saurabh had been at work on establishing a surreal little transmission station in the middle of the battleground — a phoneline and a laptop, the sparkle of its screen under the inky sky like a piece of the moon fallen on dark earth. The story was on its way. But suddenly the cold air crackled and a wave of splinters flew overhead like lightning. I was down in the cold dust and Saurabh was down but his hand was still clutching the laptop’s side, keeping it safe on an unsteady wall of sandbags. A few moments later came another burst of shell fire, zooming above the camp and disintegrating into the banks of the Drass river behind us. “Send it across,” Saurabh urged, as I read on from the fluorescent screen, “There’s time. Send it across quick. We’ll take a chance, go ahead.”

After a brief lull, the bombardment and counter-bombardment had resumed its high pitch and the pitter-patter had turned to rain. Artillery guns were belching fire from Drass valley’s dark belly and from behind 5140 rose recurrent flashes, lightening up the sky: Pakistani guns responding. They were landing all over the place, rustling up the darkness. But Saurabh held up the screen till the last line had been read out.

Around midnight, 5140 was lit up with a hail of flares; it was like a display of fireworks but this wasn’t anyone’s entertainment. Nobody was quite sure who was firing them: it could have been the Indian forces trying to expose Pakistani positions around the peak for the infantry to hit, but it could also have been the Pakistanis trying to locate Indian troops trying to close in. Each burst of flares was followed by rounds of machinegun fire, echoing eerily in the night.

From the pit of our dark bunker — we were four in a four by four hole in the ground — we heard the fire fly across and thud in the vicinity all night. There was a brief break in exchanges but by dawn, when the first supply convoys begin moving up to Leh via Drass, precision shell fire on National Highway 1A intensified again. The gaily coloured trucks, carrying essential commodities that sustain Kargil and Leh through their long isolation of winter, hurried past the camp in semi-darkness, riding their luck as much as their tyres, mulching on overnight rain.

Daybreak revealed more troops preparing to go up, fastening their snowboots and hitching their guns and sleeping bags and hauling themselves up into trucks. On 5140, the shells were still landing and the smoke still lifting. It hadn’t been taken yet. “But,” assured a young captain, “It will fall to us soon, we are now packing our punch in this contest.”

Saurabh Das of AP, more than just groggy from a night spent reclining on a pebbly wall in a dust-ridden bunker, was at it again in the lovely light of the morning, shooting this undeclared war with his own arsenal of lenses.

Sankarshan Thakur below Tololing

This story was first published in The Telegraph in 1999