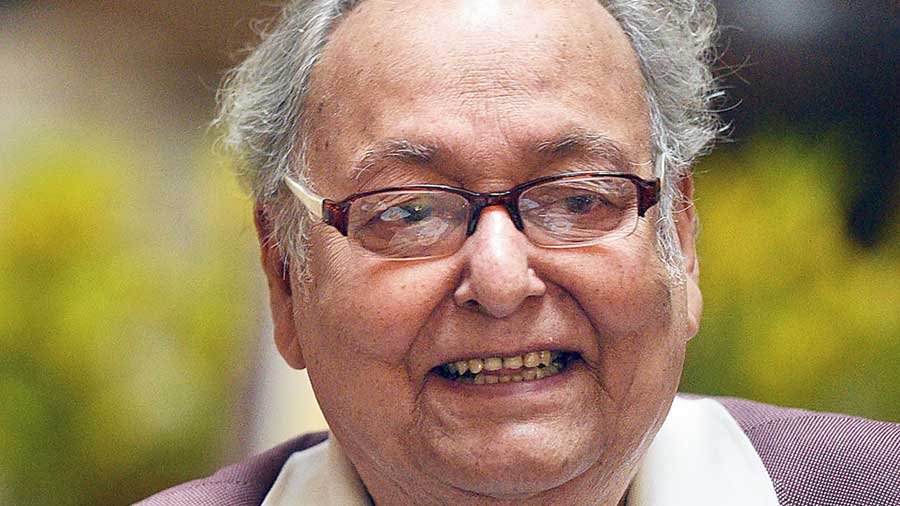

Soumitra Chatterjee was the only Indian star and actor who was also a thinker, a cerebral voice, a writer to reckon with, an editor of a journal of immense contribution (Ekkhon), a theatre director who adapted plays from European texts himself. It’s difficult to think of him just as an actor without his contribution as an intellectual in our society.

Here was a responsible husband, a father, a grandfather, a celebrated star and an intellectual who lived a genuinely middle-class life to give Bengalis and the world a very high quality of work irrespective of the deterioration of culture; one who had ample chance to live and work like a star but refused it for his love and concern for the truly intellectual. Here was a Bengali who will forever remind you of the standards required to be proud of our city.

Soumitra Chatterjee was born in 1935, spending his childhood in Krishnagar, where both his grandfather and father were involved in amateur theatre. Having acted in school and college plays, he later learnt the craft of acting from the noted director Ahindra Chowdhury. His turning point was watching Sisir Bhaduri, who inspired him to think differently as a performer.

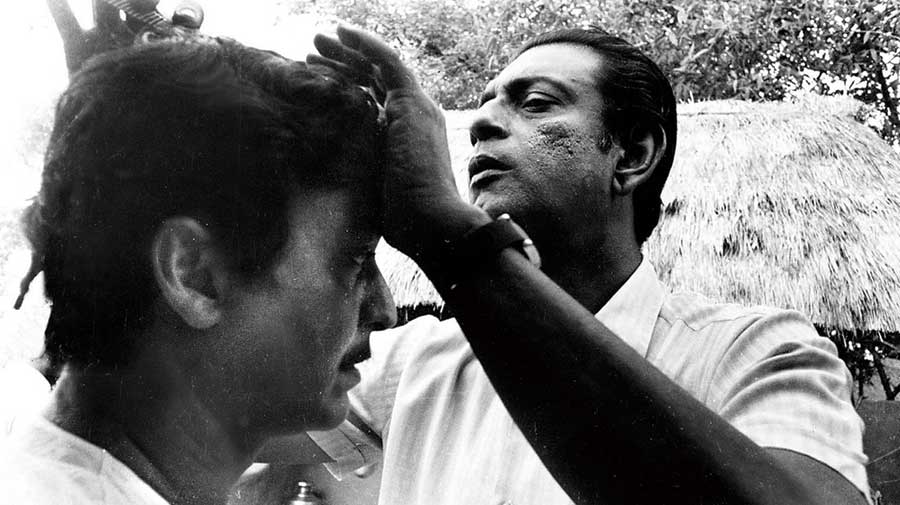

While working for All India Radio during the 1950s, he met Satyajit Ray who wanted to cast him in Aparajito but found him too old for the adolescent Apu. He was then selected for Nilachaley Mahaprabhu, which he rejected. He was finally cast in his first film by Ray in 1958, in Apur Sansar, which made history.

It’s difficult to imagine the huge gamut of directors he worked with, from the very best to the absolutely bad, never falling from his basic level of execution. I sometimes felt disturbed by his lack of choice in selecting films or serials or ads… but watching all kinds of his films, I realised, whatever be the reason, here was a creative artiste who never fell into the rut.

Before writing this I had called up that last of the Mohicans in the field of theatre and literature and a great friend of Soumitra, Samik Bandyopadhyay, whom I had continuously turned to for my theatre.

He said: “Soumitra represents that sheer intellectual performer and poet in India who has contributed to the greatest Bengali directors and yet single-handedly fought the growing mediocrity by living and working in it.”

We went on to talk about how, being a contemporary of Sunil Gangopadhyay and Shakti Chattopadhyay, who were rebels, anarchists, Soumitra was utterly and totally different as a poet and a thinker; how he completely reshaped the commercial theatre of Haatibagan with Friedrich Dürrenmatt and Henrik Ibsen. He went on to tell me how, after being diagnosed with cancer and getting treated in London, Soumitra saw a British play called No Smoking and wrote and staged a very personal, emotionally heart-wrenching play, Tritiyo Anko Atoeb.

While I was working with him as an actor under Mrinal Sen in Mahaprithibhi, which was based on my story, he interacted less with me regarding acting and more regarding the basic text. He went into great details of my experiences in Berlin and why I wrote the story.

Much later, when I directed him in my telefilm, Joybaba Rudranath (Rudra Sener Diary), a tribute to Feluda, I asked him about his association with the role. Soumitra unabashedly replied: “You know Anjan, when I became famous for Feluda, I was very disturbed since I had played far superior characters with Manikda (Satyajit Ray). Later on I realised that I had become famous because children identified with me. It was a great feeling.”

In his Gadya Sangraha, the highly perceptive critical analysis of the craft of acting and his colleagues is simply remarkable. He doesn’t merely praise legends like Uttam Kumar or Rabi Ghosh but looks at their work very critically. He writes how Tapan Sinha actually taught him to walk as a screen actor. Later, he writes how he unlearned it when Rituparno Ghosh told him to walk completely differently in his film Asukh.

When I received the Best Maiden Acting Award at the Venice Film Festival in 1981 for Mrinal Sen’s Chaalchitra, I was convinced I would take over the baton from Soumitra Chatterjee and become the new, intelligent face of Bengal cinema. Thirteen years of struggle found me ending up at his house as a director, wanting to cast him in my telefilm, Amar Baba.

Directing him and acting with him for Amar Baba was a huge experience emotionally. I never directed our scenes technically. After shot division and lensing, I let him act and did so myself. Both of us decided whether we were in the correct zone and pitch. There were scenes where he decided the length of the shot or the action. There were scenes where I, as an actor, did not cut the scene till he gave up. The result is for you to see on YouTube. I have no idea whether people work like this nowadays.

When I asked him to play just one scene as Shayan Munshi’s paralytic grandfather in my film The Bong Connection, he willingly agreed. Much later, when I cast him in a major role in my film Shesh Boley Kichu Nei, our interactive workshops began again.

I always took his shot first and then my shot. He took the exercise for a day and insisted that he redo some of his earlier shots. “You are playing a notch lower than me. I think I should play less,” he said. I embraced him with joy and told him that I was worried about his health and wanted to take his shots and release him. He insisted that he stayed and watched my shots. “You try to pack up early. It’ll help both of us.”

I did exactly that and ended up sharing two half pegs of single malt after pack-up, every day, to talk about cinema, theatre, acting, literature, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen, Calcutta’s heritage… and the prevalent mediocrity of Bengali culture.

When I cast Soumitra’s grandson Ronodeep Bose for my film Dutta vs Dutta, he was overjoyed. After watching the film he cried and said: “This is your best work, Anjan.”

Soumitra Chatterjee always regarded Balraj Sahni as the best Indian actor in cinema. Today, when I look back, it’s very difficult to think of Mr Sahni, the great actor that he was, as a poet, a writer, a social voice, a highly influential theatre director, en editor of a magazine that brought the most alternative of writers and writings to the forefront, the winner of the Legion of Honour from France. One who can refuse the National Award for his political beliefs.

While deciding what Rabindrasangeet he would sing for my film Shesh Boley Kichu Nei, Soumitra Chatterjee had suggested Aguner Parashmoni. That is the song I would love to sing for him today. I feel grateful that I have lived in his city as an actor, director, singer-songwriter, theatre director… whatever.

Anjan Dutt is a film-maker, actor, singer-songwriter, who has directed Soumitra in films like The Bong Connection & Shesh Boley Kichu Nei