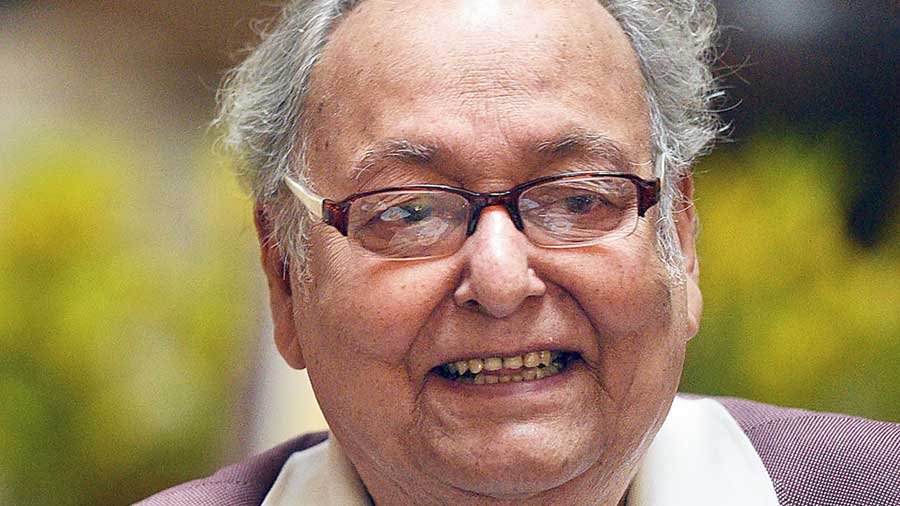

I never imagined that I would be writing an obituary for someone so full of life as Soumitra Chatterjee. Those who were lucky enough to know him at reasonably close quarters, which is quite a large number, it would really take a long time to accept that he is no more. Rarely has one come across an all-round cultural personality with absolutely no airs. He was in life as he appeared (and will always appear) in his films.

What I will never forget is his instant response when I asked him how many films he had acted in. He bowled me over with a flashy Soumitra smile and said: “I really can’t say — too tiring to count”.

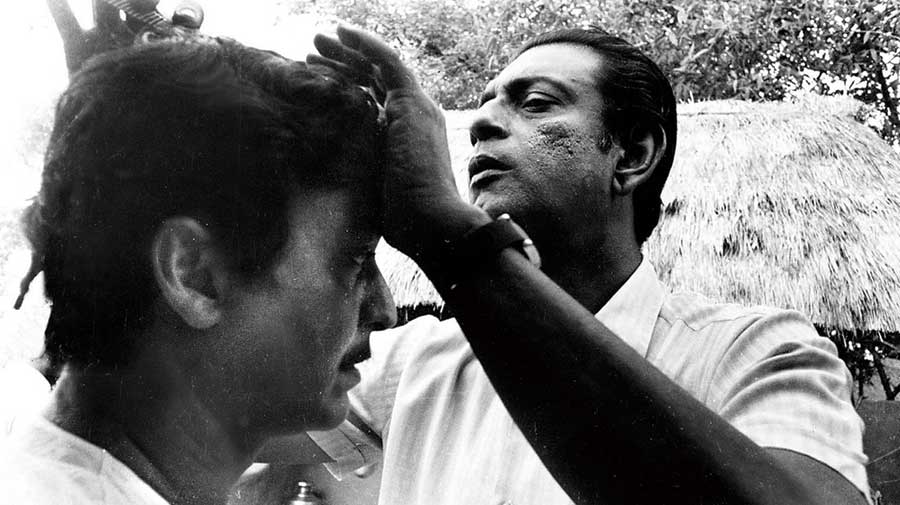

Satyajit Ray directs Soumitra Chatterjee in Ganashatru (1990), based on Henrik Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People. Soumitra’s Dr Ashoke Gupta bears the brunt of religious dogma as he tries to spread awareness about an epidemic caused by a temple’s “holy water” Sourced by The Telegraph

That was because he was always so busy, right up to his 85th year — acting in more and more films, reciting poems in his unmistakable voice, writing his own poems as well, or even stealing the limelight at public events. It was absolutely remarkable to observe the great ease with which he rushed around his programmes all through the day, and show no weariness at all in the evening — if one could get him for a few quiet sessions. He never complained or gossiped, but would be drawn instantly into discussing more troubling crises of our times.

Despite his success in films, he never stopped performing on the stage, which was his first love, since his teens. He was mentored by iconic actors like Sisir Bhaduri and Ahindra Chaudhuri. It was Mrityunjay Sil, his friend and fellow thespian, who he always acknowledged gratefully for encouraging him the most. His performance in his 75th year and thereafter in Raja Lear, the Bengali adaptation of Shakespeare, left no doubt that he was, indeed, the colossus of Bengali theatre.

A week before he was admitted to hospital with the deadly Covid-19 in early October, he spoke rather philosophically of death — at the memorial of his long-time friend and contemporary thespian, Asit Bandopadhayay. This was, perhaps, his last public talk and, for some inexplicable reason, he chose to devote some time to this troubling topic. He looked tired and said, in a somewhat melancholic mood, how death overtakes us without warning. What struck us more was his pensive remark that it would be an oversimplification to blame it only on our advancing years. He did not elaborate further and, with a perceptible sigh, he migrated from the subject to Asit babu and his contribution.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that Soumitra Chatterjee was a veritable institution in Bengal and a quintessential Bengali “Renaissance man” — if one is comfortable with using such a grandiose term. He really never attempted to overawe the “national audience”, though he did register his presence in Mumbai.

He was more at home with endless cups and intelligent conversation amidst the haze of smoke at Coffee House. He had not considered acting in films as he was convinced that he was not photogenic, until Satyajit Ray proved him wrong.

That was 1959 and he was only 24. Even in the “industry”, Soumitra was clear that he was an actor and not a star. He knew that as the good-looking, pleasant “boy next door”, he would hardly get the audience to swoon with a captivating gaze like Uttam Kumar. In fact, though the two were always compared, all the way from the 1960s, and while Uttam apparently overshadowed Soumitra, most discerning viewers realised that they were in two different moulds and excelled in their own domains.

They acted together in six films and Soumitra had no issues in playing the villain’s role opposite the swashbuckling Uttam in Jhinder Bondi (1961) — despite the risk of being branded. It was, however, Ray who moulded Soumitra, the sensitive artiste, and included him in 14 of his films, which is quite a record.

Through the master’s lens Sourced by The Telegraph

Soumitra moved from the fascinating role of Ray’s Apu to the attractive intellectual, Amal, in Charulata (1964). He repositioned himself smoothly as the troubled Gangacharan in Ashani Sanket (1973), then as Ray’s cerebral detective, Feluda, winning accolades all along. But the thinking person’s actor could also excel as a typical “street Romeo” in popular Bengali films on contemporary issues and perform with touching sensitivity as a troubled old man in his recent films, Belaseshe (2015) and Mayurakshi (2017). It was brand Soumitra that prevailed, whether the director was Mrinal Sen or Tapan Sinha or Tarun Mazumdar.

He was awarded the Padma Bhushan, though he deserved much more, and became the first Indian film personality to be honoured with France’s highest award for artists, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres.

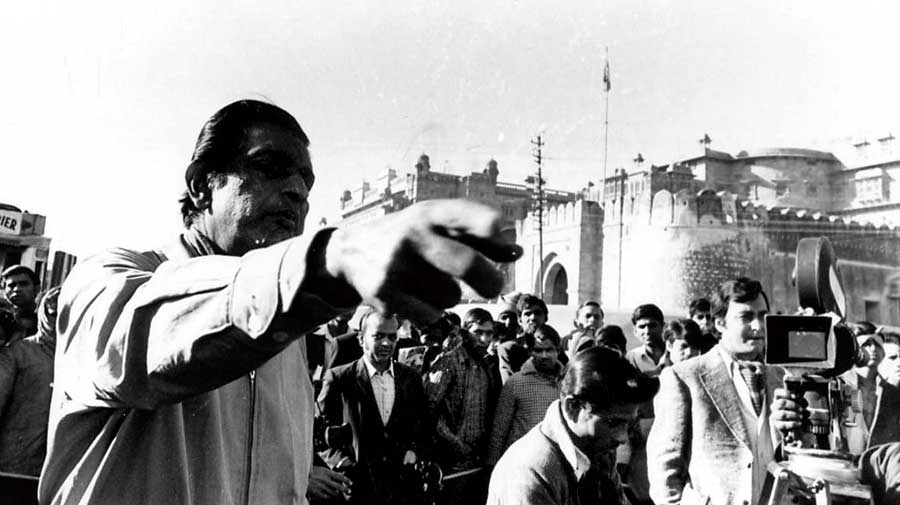

Satyajit Ray and Soumitra Chatterjee during the shooting of Sonar Kella (1974) Sourced by The Telegraph

At long last, in 2012 he was finally accorded India’s topmost award for cinema, the Dadasaheb Phalke Award. I remember very distinctly that when I met him at the huge bash that evening in honour of the National Film awardees, he was feeling genuinely exulted. But he was quite bored in the glitzy film crowd and whispered conspiratorially that we must escape soon. That was not to be as the information minister dragged him away, and I could see the disappointment writ all over his face, as the actor’s mask dropped. In 2017, 30 years after Ray was honoured with France’s highest civilian award, the coveted Legion d’Honneur, his dear Soumitra was also bestowed this coveted award.

Jawhar Sircar and Soumitra Chatterjee Sourced by The Telegraph

One could discuss the plays he wrote or the paintings he drew, but it may be more relevant to recall his association with the iconic little magazine Ekkhon. Along with the redoubtable Nirmalya Acharya, Soumitra Chatterjee set up this pioneering publication for the discerning, cerebral reader — some six decades ago. They met regularly at the Kathashilpa office on Shyamacharan De Street, which was the favoured haunt of non-party Leftist intellectuals those days.

Soumitra Chatterjee never wavered in his beliefs, even when the word “Left” invites the wrath of regimes at the Centre and in the state. Though he was not aggressive and tried to be tactful, he never allowed himself to be co-opted by the establishment — not even when the Left ruled. His circle of friends knew full well what he thought of the present regimes and one will miss his encouraging messages when we took potshots at them.

So, when we see the condolence tweets of a powerful national leader or watch how another walks extra miles on Soumitra Chatterjee’s final journey, one is dead sure how he must have chuckled all the way.

Jawhar Sircar is former culture secretary of India