His flight from Calcutta was delayed by several hours. With a deadline looming large, I was in a flurry as I waited at the airport. But when Zakir Hussain’s flight finally landed, he walked up to me unperturbed. That was the day he introduced me to equanimity. “Once you’ve done your best and things are out of your hands, breathe easy. That’s how I largely retain my composure.”

From that day onwards, I’ve tried to follow his advice. It works.

In an interview I once did for Savvy — Zakir was a women’s favourite — the inveterate traveller had spoken about not going on a guilt trip after a one-off cheat-day binging on stuffed parathas at a dhaba and on handling last-minute packing or unexpected changes in his schedule. “I have a small bag ready with my passport, my cards and some currency,” he told me. “I can pick up the bag on short notice and catch a flight to anywhere. From toothbrush to clothes, I can buy almost anything wherever I go.” Small, no-fret tips from an Ustad.

One of his most unforgettable moments was when he went like an average tourist to Dharamshala. The Dalai Lama had walked through his audience but had stopped, turned back and gone up to Zakir. The Buddhist monk’s blessings that day had underscored that even without being announced as a celebrity, Zakir stood out as someone unique.

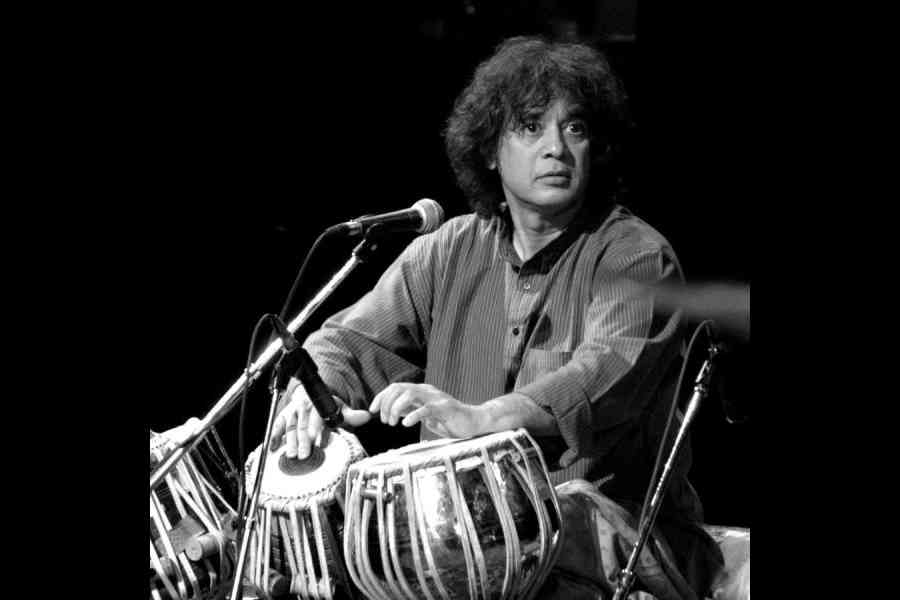

Zakir had a unique sense of humour too. He’d once been named the sexiest man in India. With this curly mop all over his forehead, he’d laughed, “I wonder where they got that from... I stay hidden behind a pair of tablas.”

An interesting remark he made about not seeking centre stage came with the explanation that a tabla player is “essentially an accompanist, used to accompanying the main player”.

But the accompanist who soon charmed an audience of his own all over the world, observed other artistes with a keen eye. During one of our many interactions, he likened Shabana Azmi to doyen Kishori Amonkar.

“At least once in every performance, Kishoriji will hit an outstanding note and take you by surprise. Shabana has a similar quality. In every performance, she’ll give a shot that’s so exceptional, it’ll make you sit up and applaud. ”

Rare female tabla player Anuradha Pal had the good fortune of sitting on Zakir’s lap when she was only five years old. “Aapko bajana hai?” he asked the curious child and placed her tiny hands on the tabla. He became her Guru for life, teaching her in his own disciplined way how to balance the left hand with the right or to think unconventionally. Zakirbhai finally bestowed on his student one of her most cherished compliments for being “one of the earliest ones to break out, without worrying about social repercussions”. Anuradha’s annual ritual of seeking his blessings on Guru Poornima ended this August when he praised her musical innovations like “Ramayan on the tabla”. That was also the month he last paid tribute to Abbaji Ustad Alla Rakha, his father and guru.

Winter after winter, Zakir would fly down to India, his diary crammed with concerts. He had two “musts” in February. One, a tribute to Abbaji on his death anniversary. Another on February 28 when he’d design a scintillating show, a different one every year, invite other artistes to join him and perform in memory of Jennifer Kapoor.

Nalini Uchil, my colleague at Star & Style, once took on the impossible assignment of bringing Kamal Hassan and Zakir together for a photo session. When she did pull it off, it happened to be her birthday. The shoot is your birthday gift, said Kamal to her. Zakir took the birthday girl out to dinner. These little touches were what made Zakir the person he was. Beyond the talent, beyond the success, a maestro who connected with people, with his audience.

The music scene in the winters of Mumbai will never be the same again. Farewell, Ustad.