One of the most prolific documentary film-makers in the world, Gianfranco Rosi has made some powerful and poignant films in the last three decades. The 57-year-old Italian-American film-maker won the Golden Lion at the 70th Venice Film Festival for his 2013 film Sacro GRA and the Golden Bear at the 66th Berlin Film Festival for his 2016 film Fire at Sea.

Rosi is the only documentary film-maker to win two highest awards at the three major European film festivals — Venice, Berlin, and Cannes — being the only director, along with big names like Michael Haneke, Ang Lee, Ken Loach and Jafar Panahi, to do so in the 21st century. Rosi was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature for Fire at Sea.

Rosi’s latest documentary Notturno casts a keen eye on the Middle East ravaged by the ISIS and captures the aftermath of war. With Notturno premiering on MUBI today, The Telegraph chatted with Rosi over Zoom on the film, what keeps him invested in his art and his experience of shooting his first film in India.

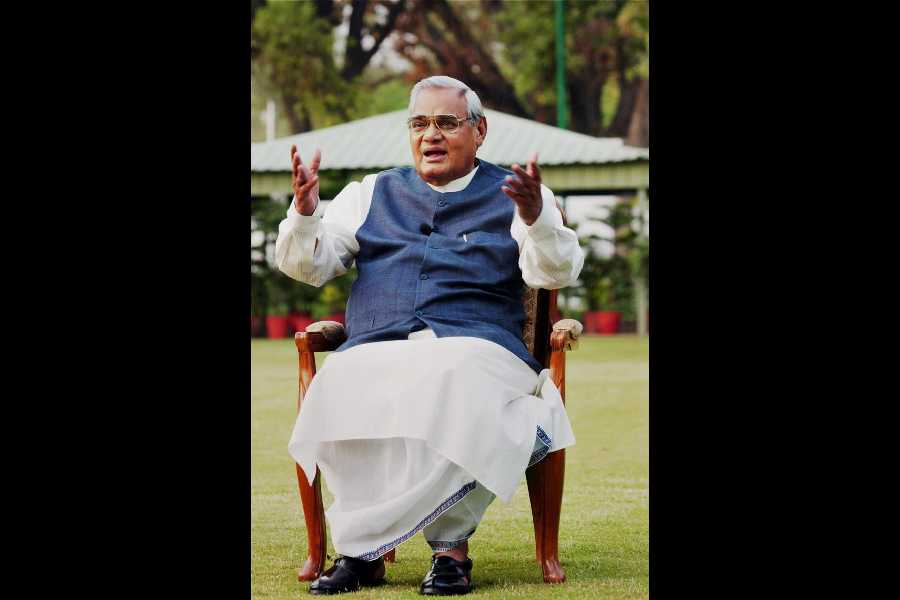

Gianfranco Rosi Sourced by the correspondent

War affects everyone and Notturno affected me in many ways because it talks so succinctly about the human cost of war. Was there a specific trigger that made you want to make this documentary?

My previous film (Fire at Sea) was set in Lampedusa in Europe where thousands of people arrived from countries that are affected by war. Fire at Sea filmed that first approach of migrants arriving in Europe. After I finished it, it was a natural need on my part to cross the sea and see the area where most of the people I met in Lampedusa had come from.

That’s when I started this journey of Notturno. It was a time when the state of ISIS was collapsing and all the disaster that ISIS had brought in in the last five years had given way to a hope of rebirth in that area. I started creating the journey of this film in a place that was essentially the border between life and hell. That was the first step, and then it took me three years to put the documentary together. I was a one-man crew and I had some incredible local people helping me in Kurdistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria.... It was essential for me to go and meet the people who had suffered the destruction brought on by ISIS because if I didn’t meet them, it wasn’t possible for me to sit in a room and write about them.

You’ve said that you wanted Notturno to be ‘a film of encounter’ and you spent months at real locations talking to people who were suffering, but you didn’t carry a camera. Weren’t you apprehensive about missing out on important footage?

I didn’t carry a camera because a camera changes relationships and the way people react to you. It was very important for me, in the beginning, to just go around and talk to people without the pressure of filming. And on that journey, I somehow realised that making a film is as much about missing things as it is about capturing them.

Without the camera I felt a certain freedom in talking to people without trying to capture everything in an image, and even they felt unencumbered while talking to me about their deepest emotions and fears. It helped me gain their trust, and I just met people randomly. There was a hunter going on a motorbike and I just stopped him in the middle of the road and started speaking to him. We got so friendly that he took me to his house. After eight months, I went back to film and he was like, ‘Okay, you didn’t betray me... you really want to tell my story’. I forged strong relationships before I took out the camera. I spent so much time there with those people and made them so comfortable that they didn’t even realise when I took out the camera and started filming them. I became a participant in their lives and their stories, than just a film-maker.

We see images of mothers mourning the deaths of their young sons, a stuttering child who describes fleeing the ISIS.... Given that the material is so deeply unsettling, what were the biggest challenges for you as a film-maker, and more importantly, as a human being?

I didn’t know the language there... so that was a big handicap as a film-maker. It was the first time I filmed without the knowledge of the language. I also had to grasp the culture, which is so huge and so difficult to describe... Iraq is different from Kurdistan as much as Lebanon is different from Syria. Since I didn’t know the language, their body language and what they were saying through their eyes was a sort of conversation for me.

The one thing in common between them is that they were all victims of ISIS. The devastation was not only physical, but also psychological. All the people I met had some sort of memory that had scarred them. The sense of wait, the sense of a future that’s suspended... that’s common to all of them.

After spending three years there, I came back to Europe only in February 2020 and the lockdown started all over the world in March. We were facing an invisible enemy in the form of Covid-19 and for the first time, like those people, I felt the future of the globe was suspended. That’s when I realised that the story that I tell in Notturno is universal. Of course, there is a difference. I have a roof over my head and money in my pocket and people in those countries don’t even have a house. But the sense of suspension, the fear of facing the unknown felt familiar. The film articulates this penumbra, this feeling of understanding what you don’t always see. That’s why I called this film Notturno, signifying a night where you don’t recognise many things. Notturno, for me, is a mood, a state of mind that’s physical, but also emotional.

You are, of course, a film-maker, but would you also call yourself a nomad, given the stories that you tell?

(Laughs) I always say that I live where I film. I immerse myself completely in the place where I go.

I become a citizen of that place when I am there. I lived in Lampedusa for two years and in the American desert for five years. It took me five years to make a film in India. I lived in a camper close to Rome for two years. Where I live becomes my reality. Anyway, our brains are very nomadic, we go from one thought to another. But I have to do that also physically when I make a film.

What is it about the art of documentary film-making that you love so much?

It’s become my way of life. I treat every film as my first and as my last film. When I make a film, I don’t have a family life anymore (laughs). I keep saying I don’t want to do it anymore, but I change my mind every time (laughs).

Film-making is an intimate experience for me. Time is my biggest ally when I make a film. Sometimes I have to wait for three weeks for the right light to film a single scene. I have amazing producers who trust me and give me complete freedom. I am probably one of the very few documentary film-makers in the world who can start a project by just writing three-four pages of the script. My thinking of a film is never structured in a script and I love that as a film-maker.

What were your years spent in India like while you were filming The Boatman?

I was very young, I was coming in from film school and it was my thesis film. It took me five years to make that film. I had never encountered death before and when I went to Benaras, I realised that it’s probably the only place in the world where dead people and those who are alive are constantly in the same space. You just walk somewhere and you see a funeral happening or encounter a dead body. This spiritual acceptance of death is something that I found incredible. It made me realise that death is part of life.

When I first arrived there, there was a curfew because of riots and I had no conveyance from the airport. I saw a truck arriving and I asked them for a lift into town and at the back of the truck, there were 10-15 people sitting around a dead body. So I went from the airport to the city with a dead body!

I shot The Boatman completely on a boat in Benaras and that’s where I learnt where to put the camera, how to set the frame and how to tell a story. It took me years to put together a one-hour film but that’s the film that taught me all I know about film-making. It took me 10 years to make another film after that incredible experience.