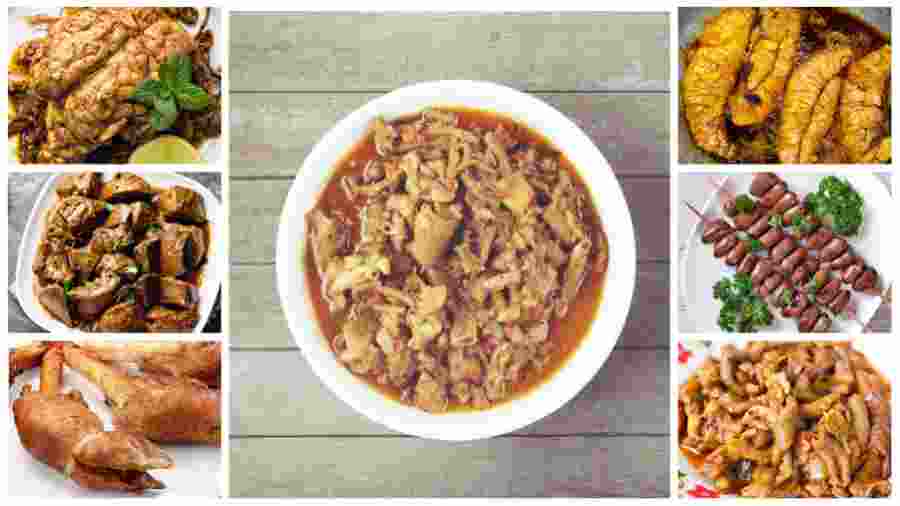

The chaiwala points to a distance where the lane merges into Bentinck Street in central Calcutta, and says, “Every evening he sets up shop there.” A man in a red-and-white striped T-shirt who is hanging around the tea stall with a flask interjects, “He is gone.” The tea seller looks annoyed. He snaps, “He will be back,” and continues, “He sells khasir chhaat, murgir chhaat…” Chhaat is the general term for offal.

“Hebby jhaal… very spicy,” the man in the T-shirt is relentless. So who eats at that twilight shop? “Bhalo-bhalo loke khaye,” he is emphatic. Now, bhalo means good in Bengali, in this context it could also mean decent, regular, respectable. The chaiwala gives the interloper a withering look, then says, “Customers are labourers who work and live in and around this area. Muslims, Biharis… very few Bengalis.”

Offal is widely consumed in Calcutta and across Bengal. Amitava Purakayastha, who conducts food walks in north and central Calcutta, knows of other shops like the one on Bentinck street; in Entally, in Nagerbazar.

He says, “These are to be found around shops selling Bangla mod (country liquor). Chicken gizzard, liver and feet are used to make a jhal jhol. The fiery taste complements the heat of the liquor.” Depending on who you ask, this dish is called chatpati, moder chaat, chaat.

Purakayastha continues, “People also eat bot… intestines.” He talks about a shop in Janbazar that sells bot and ruti.

There are people who eat rakti, a spicy dish prepared from coagulated goat blood.

Swapankumar Mandal, a schoolteacher, describes prawn heads ground and fried with besan, and machher teler charchari (fish fat in a vegetable mix); they are popular in Sonarpur and Garia. He knows of tengri (mutton leg bone) juice being paired with alcohol in the Panagarh-Burdwan region.

In the North and South 24-Parganas, at weddings and festivals when five or six goats are sacrificed, those tasked with the killing take away the lungs and brains. These are fried and eaten. In Champahati, at sundown, he has seen labourers snacking on ghugni, a dish of chickpeas, made with either goat intestine or chicken feet. Muri (puffed rice) and chhaat is also eaten by many.

Shakti Bhattacharya, who has scoured practically all the districts of Bengal for research, will tell you that in Bankura and Purulia they eat feathers cooked with potatoes. Chicken sells at Rs 200 a kilo and mutton for Rs 800, but organ meat costs anything between Rs 40 and Rs 100 a kilo; buyers can make a complete dish with as little as 100 grams even. Trotters perhaps are the most expensive and cost Rs 60-70 a piece.

Pompa Das, who travels daily between Mograhat and Calcutta, knows of families who do a bhetki bone dish with aubergine. Tribal activist Laxmi Mandi says in West Midnapore they cook fish fat with pumpkin and vegetable marrow and do a goat head kosha.

Basanti Sardar cooks for three families in Calcutta. She has seen her sister in Kella in South 24- Parganas use fried fish scales in panchmisali. Khokon, a fishmonger, says the scales of the ilish are also eaten. And at the north Calcutta meat shop, a customer buys two kilos of mutton and also asks for gole (goat testicles).

Jayanta Sengupta, best known as the curator of Victoria Memorial Hall, is primarily a historian. In a 2009 paper, Nation on a platter: the Culture and Politics of Food and Cuisine in Colonial Bengal, he has written about some of the first few Bengali cookbooks — Pakrajeswar, Byanjan Ratnakar — and even 19th-century journals such as Punya, edited by Prajnasundari Debi, which had recipes. Did they contain offal recipes?

Sengupta says, “Offal was not part of the bhadralok foodscape, though Prajnasundari writes about collecting gelatin from sheep’s hooves to make orange marmalade, and Pakrajeswar and Byanjan Ratnakar make references to chhagadi mundo, chhagadi nari and a dish made of liver, kidney, lung cooked with garam masala, ginger and garlic, respectively.”

He continues, “I think the absence of offal is a dimension of upper-caste dominance in Bengali culture, and its difference from the demographics of Kerala or Goa.”

The attitudinal difference becomes apparent when you hear Crescentia Fernandes talk about her mother’s kitchen in Ernakulam and her wondrous brain cutlets, heart stuffed with keema and “tasty” oxtail with roasted masala. Born in Kerala and married into a Goan family, Fernandes and her husband ran a popular Goan restaurant in Gurgaon for many years.

She tells The Telegraph how in Goa, traditionally, every part of the pig is used. “Good bits” go into roasts and vindaloo, the big bones with flesh on them make up the aad maas and the spare bits — ears, tail, snout — go into the sorpotel. “Also the blood,” she adds.

Fernandes remembers khiri (udder) kebabs from Calcutta of the 1970s. The long-gone Skyroom restaurant on Park Street used to offer kidney on toast.

Manzilat Fatima, a fifth-generation descendant of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah who married into a Bihari Muslim family, is a custodian of heirloom recipes. Awadhi cuisine includes bheja and gurda, and Bihari Muslim fare includes zubaan, siri, kaleja. Fatima knows of dishes cooked with jhaar — the gaggle of heart, liver and lungs, so called because it resembles a chandelier.

She recalls how her mother-inlaw was particular about the trotter, a delicacy. “The butcher yanks off the skin, pulling away the soft meat. We used to get the trotter, skin, shoe et al, put it in boiling water and scrape the hair off with care before cooking it.”

Fatima’s family has lived in Bengal for generations now. The people of Champahati, Sonarpur, Mograhat and the Sunderbans… also belong to this state, no? And still, the unspoken and widely accepted belief is “We don’t eat offal”. It begs the question — who is this “we”?

Mandal says the definitions of “Bengali”, “Calcuttan” and “mainstream” are constantly shifting. He continues, “Those in the peripheries are moving to Calcutta, and the people here are moving out to Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, abroad. That is how a variety of dietary practices are inserting themselves into the old menu.”

Purakayastha credits this intersection and democratisation of tastes to the railways. Bhattacharya believes the driver of change is the woman in your kitchen cooking your daily meals with her roots in Malda, Midnapore or Canning.

The poor living in the hilly regions of Darjeeling, Kalimpong and Sikkim eat momos made of pig or chicken chhaat with dolle, a chilli chutney.

Saibal Bose, who teaches in a school in Jalpaiguri, knows that some of those impacted by the closure of tea estates make and sell this food for a living. He says, “Even Bengalis living in the plains eat these.” He attributes this shift to the youth, their cultural curiosity, their travels and their obliviousness to old prejudices.

This ties in with the efforts of Amar Khamar, which among other things does table pop-ups in Calcutta showcasing suburban dishes. Recently, at a Sunderbans-inspired pop-up, chef Preetam Bhadra served his “interpretation” of dishes prepared with the country rooster’s heart, liver and gizzard.

To challenge some enduring impression of Bengal and its relationship with offal is not the point of this piece. No intention either to raise questions about what is a Bengali diet and if it equals the Bengal diet.

Just remember what the interloper said — “Khaye. Bhalo-bhalo loke khaye.”