Meine herzensgute liebe Mutti... My dear dear Mother, begins the letter from a German soldier posted in Stalingrad in the winter of 1943. It continues, “On your birthday I wish you my dearest loveliest Mother... Please celebrate well in our dear homeland. Really nicely and cheerfully. I only wish I can be healthy and be in your arms one day... immer an dich denkenden... always thinking of you. Your son.”

In January that year, when it became increasingly evident that the German forces were fighting a losing battle, Hitler extended to his troops the privilege of a last letter home. The meaning of this largesse was not lost on the soldiers. In another letter, another son writes to his father. “Dear Father, you are a colonel, you understand these things. I think we have another eight days and then it will all be over. Tell mother however you want to.”

In due course, an aircraft was sent to Stalingrad to collect the missives. They were never delivered. Instead, they were opened, read, sorted, and the names of the writers and recipients’ addresses were blackened. And then they were handed over to the Nazi intelligence unit for psychoanalysis. The unit apparently feared that in the face of imminent defeat, these letters in the wrong hands might be used against them.

Life truths have a way of seeking out the most needy legatees, even from the other side of life. And there could not have been a better time to discover Juddhokshetro Theke or From the Warfront, chiefly a compilation and translation of letters written during World War II by Nazi soldiers fighting the Soviet forces in Leningrad, Stalingrad, Moscow, as also those of Red Army men in the siege-torn Soviet Union.

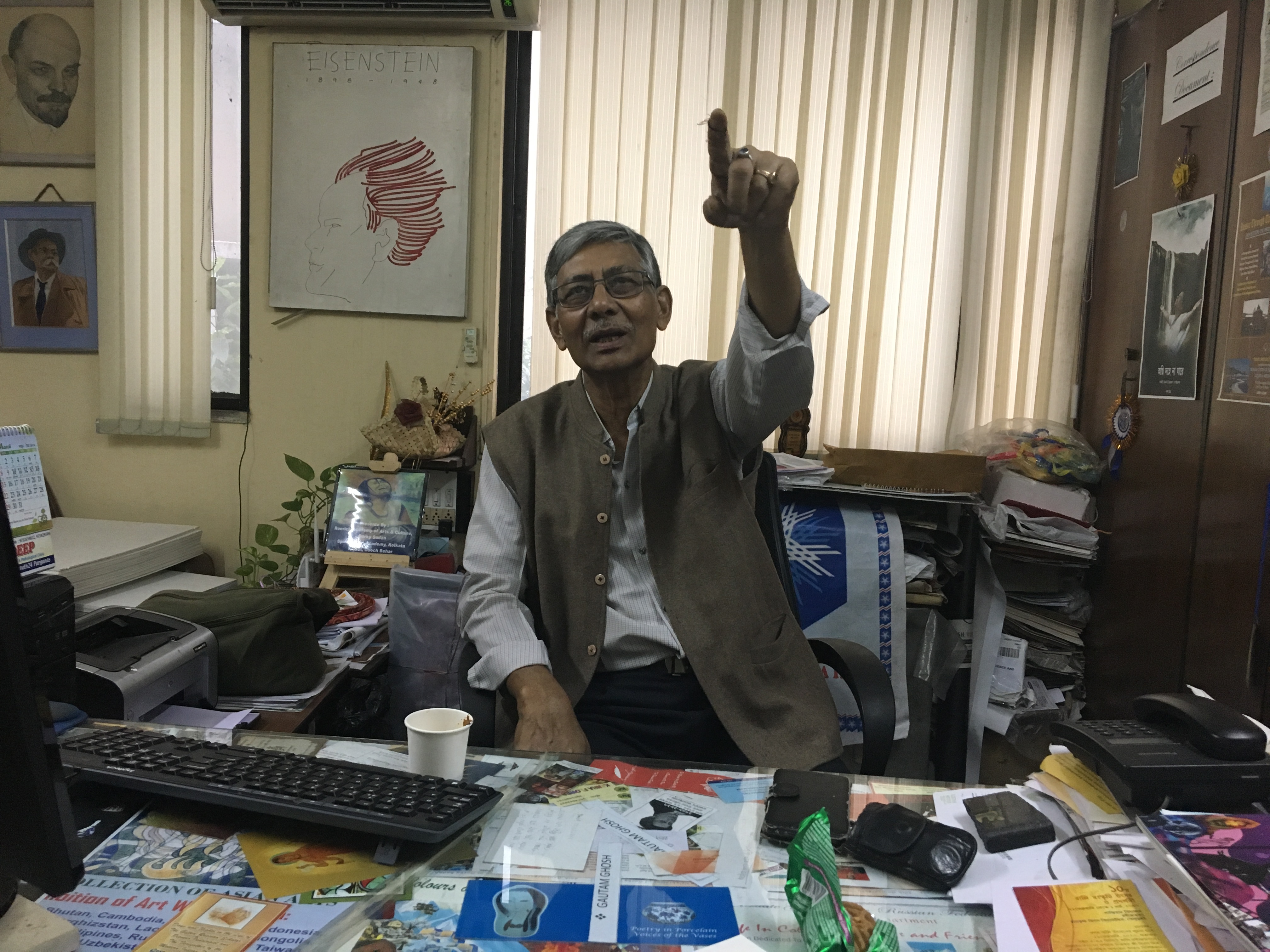

The 2019 Bengali book is by Gautam Ghosh — not the filmmaker but the senior executive programme officer at the Russian Cultural Centre in Calcutta. Says Ghosh, “When we at Gorky Sadan were planning different events and activities to celebrate the 50th year of the victory of anti-fascist forces, there was a proposal to bring out a commemorative book.”

Turns out this book has been in the making the last 25 years, during which time Ghosh has assiduously tracked and pieced together the primary material from journals and archives — personal and institutional.

Gautam Ghosh (Pic: Upala Sen)

It is entirely possible to read this compilation without a sense of the man behind it, but that would be a diminished reading. Ghosh belongs to the generation that had no world wide web at click and fingertip, but knew the world through more effort and more intimately, not so much to claim ownership but to engulf it in a warm familial embrace. But naturally, a conversation with him is a whirlwind of names, places and anecdotes pronounced with respectful familiarity and varying degrees of passion — Vietnam, Bangladesh war, Pune, Leningrad, Ghasiram Kotwal, Don Quixote, Lebedev, Eisenstein, Balraj Sahni, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen...

Long before Juddhokshetro assumed its current form, Ghosh shared his discoveries with audiences at readings in Gorky Sadan and also at events organised by the centre outside Calcutta. “I had come to know of the existence of these letters from Soviet filmmaker Roman Karmen’s documentary on World War II,” Ghosh tells The Telegraph. He adds, “At some point, after I had read the letters from both sides, the differing ideologies fell away like husk and all that I heard were very relatable, universal human concerns.”

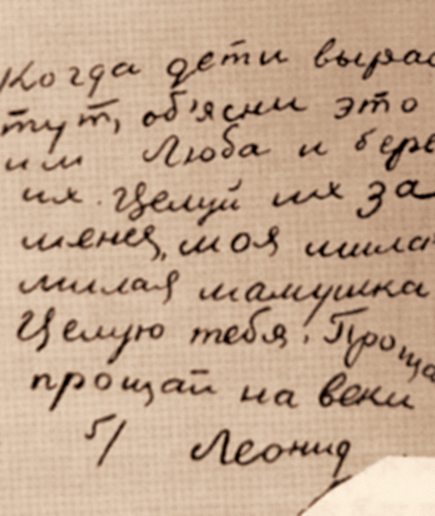

Leonid Sylin’s letter to his family (Pic: From the book Juddhokshetro Theke)

Sample these. Husband to wife: “I know you will miss me, but don’t turn away from others who reach out. Grieve for a few months, but not more; Gertrude and Klaus will need a father…” Another letter reads thus: “I know this will be the last letter. You know that I always wrote to you and her. More to her than you… But today when I have to choose for the last time, my thoughts turned to you, my wife of six years. I hope this last gesture of respect will comfort you. Please forgive me… Please go and see Carola and tell her she was very dear to me, very…” And this one by a former pianist to one Margaret recounts in some detail how he has lost the little finger of his left hand and three fingers from his right hand but is still better off than the man next to him who has lost his nose and cannot cry anymore even if he wants to.

At the readings, Ghosh says he had noticed the stunned silence of the audience. He talks about how the last letters have the feel of a sieve, distilling final illuminations. The soldier telling his general: “There is no victory, only a flag and some men who are falling like leaves off a tree. And soon there will be no flag either, nor any men.” The soldier telling his adoptive father that he has looked for God in the warfront, “…in the craters created by canons, in the hideouts and in the face of friends, but to no avail”. The 15-year-old Katya in Nazi captivity urging her father to avenge her and her mother.

Leonid Sylin writes to his children: “I didn’t come to war to prove personal bravery. I did it so you could have a better life.” The same man urges his children to look after their mother ad nauseum. He writes, “Take care of her, respect her, pay heed to her words…Study. Don’t forget me.” Nikolai Kuznetsov signs off quoting Gorky. A general’s son tells his father, “The siege of Stalingrad was not necessary. It was an unnecessary and risky political mission.”

Says Ghosh, “In this world, nothing is ever lost. And we have to ensure that nothing is lost.”