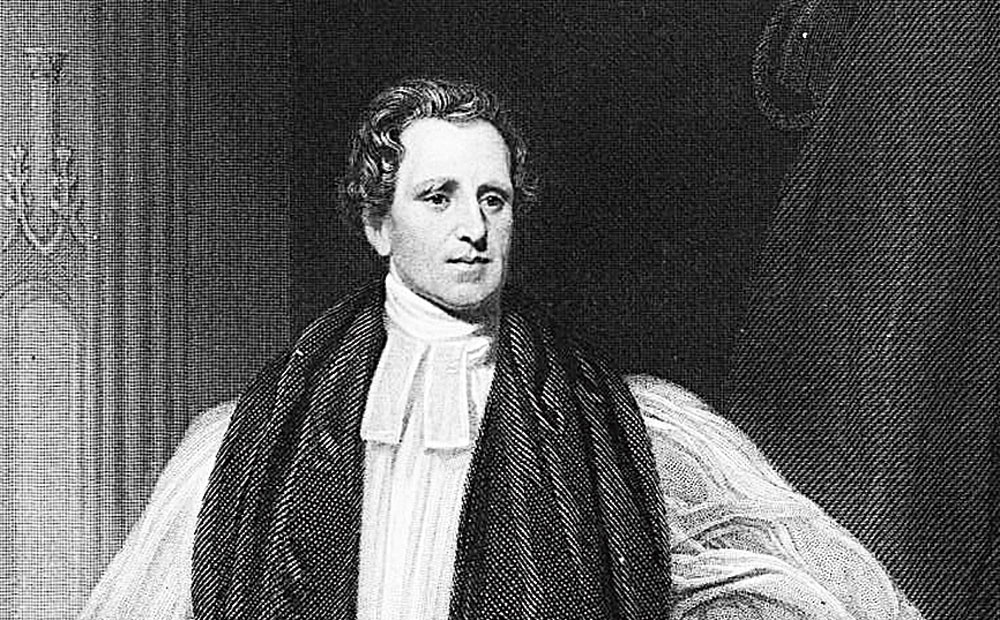

Sometime ago it was reported that the coffin of Daniel Wilson was found in a vault under the main altar of Calcutta’s St. Paul’s Cathedral. Wilson was the fifth Bishop of Calcutta and founder of St. Paul’s, which came up in 1847.

“This is not some out-of-the-box discovery. We were all aware that the coffin was kept there,” says an official from St. Paul’s Cathedral who does not want to be identified. He continues, “In fact, there is a small opening on the outer wall of the cathedral for ventilation. It was kept covered so that no stray dogs could go in. We could see the ornamentation on the coffin. The remains of the bishop were never missing. It was just that we had never gone down into the vault.”

It seems Wilson himself had made provision for the vault under the altar. “There is a reference to his musings in the book, The Final Report of St. Paul’s Cathedral, Calcutta, written by Archdeacon Pratt, who was a close associate,” says senior researcher Mary Ann Dasgupta.

St. Paul’s is said to be the first Anglican cathedral of the Victorian age. In his book, Splendours of the Raj: British Architecture in India, 1160-1947, Phillip Davies writes: “The building was constructed in a peculiar brick especially prepared for the purpose, which combined lightness with compressional strength; the dressings were of Chunar stone, and the whole edifice was covered inside and out with polished chunam.” Up the stairs of the cathedral and next to the main door is a marble bust. Would that be of Wilson? No, it belongs to Reginald Heber, who was Bishop of Calcutta in 1827.

The bust of Reginald Heber in the cathedral Picture by Pradip Sanyal

The story goes that when Heber’s bust was sent from England, Wilson couldn’t find a suitable space to display it. St. Paul’s hadn’t been built and St. John’s Church in BBD Bag, often referred to as the “old cathedral” in later years, was not spacious enough.

In a proposal written in 1839, Wilson wrote, “...subject of reproach, not only to the good taste, but to the piety of the greatest Empire in the Eastern world, that our Government House, our Mint, our Town Hall, our Custom House, our Bridges and even our Ghats... to say nothing of our official residences and private dwellings... should be upon a scale in some measure correspondent with the position we hold in India, whilst our Cathedral [St. John’s Church, built in 1787] is mean, inappropriate and incommodious...”

Heber’s bust became the peg on which Wilson put forth an application to the government for a site for a new cathedral. He wrote to Lord Auckland: “I beg permission to enquire of your Honour and the Government of India whether it would be possible to grant me a small angle of ground on the Esplanade near the Chowringhee Road for the purpose of erecting a Church.” Auckland gave consent and land and signed his missive “I am Your Lordship’s most truly Auckland”. That was May 1839. Eight years later, St. Paul’s Cathedral was ready.

Dasgupta is working on the history of St. Paul’s. She says, “It is not possible to explore the history of the cathedral without delving into the history of the man who founded it.” She has visited the library at Bishop’s College, St. Xavier’s College archives and the Asiatic Society.

Daniel Wilson was born in central England’s Spitalfields in 1778. The eldest son of a wealthy silk manufacturer, he was barely in his teens when he joined his uncle — an even wealthier silk manufacturer in London — as an apprentice. The young Wilson was, however, more inclined to religious studies than business. He pursued higher studies and eventually graduated from Oxford University and was ordained a priest in 1802.

Wilson was a vicar in north London when he accepted the call to become the Bishop of Calcutta. In Wilson’s biography, his son-in-law Josiah Bateman, writes: “In October 1797, Daniel Wilson felt his spirit stirred to go as a missionary to heathen lands; and in October 1832, he stood on the banks of the Hooghly as Bishop of Calcutta.”

From her explorings, Dasgupta has pieced together a portrait of Wilson. Wilson, the disciplined man. Wilson, who did not like wasting time. Says Dasgupta, “Most of the previous bishops of Calcutta did not survive for long, most probably due to the hectic schedules they had to follow. They used to go for long tours — Burma, China, Malaysia. Bishop Wilson did not do this at the onset. He waited for some time to adjust to the climes. He took care of his health.”

Bateman writes, “His personal habits at this time were very simple and regular. He rose early, and rode on a small black horse, brought from the Cape, which for a time, was able to take care both of itself and its master...”

We learn that he was a prolific letter writer and well-read in the classics.

“He had friends back in London with whom he would correspond,” says Dasgupta. In one letter to his children dated 1840, he wrote about the construction of the cathedral. It read, “Every morning I ride round on my horse and watch the different views which the Cathedral will present (sic).”

Besides being a devout Christian, Wilson was a dynamic man, full of energy. According to his biography, the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Calcutta in 1832 was far-reaching.

Bateman writes, “It was manifestly a burden too heavy to be borne. It must not be supposed that he found abundant records, well-defined duties; and established precedents... The Palace was a blank, the correspondence of his predecessors with the Government and clergy had disappeared, and the Registry contained little but a list of licensed chaplains.”

The coffin of Daniel Wilson was found recently at St Paul’s Cathedral in a vault under the main altar Wikipedia

Bateman elaborates, “Sixty or seventy servants, turned loose into the house, and speaking an unknown tongue, had to be recognised and mastered. Guests were to be entertained, and sick friends watched over, nursed, and cheered. It will easily be imagined that some time elapsed ere light shone upon this darkness, and order issued from this chaos.”

Wilson loved good food and people and had a reputation of being a great host. Dasgupta has read his journal entries where he writes how “the wonderful young editor of Friend of India” had breakfast with him and so also “Mr Hunt, the great railway man” and Mr Wylie, “who is one of those noble, kind-hearted, thoroughly good men, of whom there are so few in the world”. Yet another entry reads, “This morning I had all my Cathedral clergy and their wives to breakfast... there were 46 present.”

But when engrossed in work, the same man did not like being disturbed and could be very impatient. Dasgupta says, “Before the visitor would settle down in his chair, Wilson would start up in a hurried but determined way and say, ‘Well, my dear friend, you must excuse me; good morning, good morning, here is your hat and here is your umbrella,’ and before the visitor left the room, he would again be buried in his books and papers. But he was always polite in his approach.”

The day Wilson formed the St. Paul’s Cathedral Committee, he also announced that he had signed his will. Dasgupta came across a photocopy of it. In it, he states that he has given Rs 1 lakh for the building of the cathedral and another lakh will be paid out after his death. He also bequeathed his grand collection of 8,000 books to the cathedral library.

He died in 1858. Fifteen years before that he had inspected the vault which was being built for him under the communion table. He wrote in his journal:

“I could not but think as I walked up and down the abode of death how soon I might be called to lay down my pastoral staff and rest in that bed or grave as to my mortal frame, till the Resurrection morn (sic).”