The Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden in Howrah does not have the clinicality one associates with any address of science. Some things have been allowed to grow wild, and then there are other patches that are plotted and pruned and manicured. All in all, it is difficult to believe that these 270 acres of greenery contributed more useful and ornamental tropical plants to the public and private gardens of the world “than any other establishment before or since”, as wrote botanist Joseph Dalton Hooker in his 1854 book, Himalayan Journals.

It all began with one missive. “I take this opportunity of suggesting to the Board [of directors of the East India Company] the propriety of establishing a Botanical Garden... which ultimately may lead to the extension of the national commerce and riches,” wrote Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Kyd in a letter to the Governor-General in 1786. Kyd suggested that the garden be used to grow cinnamon, cloves and pepper.

At the time, the Dutch ruled the spice trade. Greedy to tap into into spice lucre, the East India Company accepted Kyd’s suggestion with alacrity. He was named superintendent of the proposed garden. And in 1787, the vast acreage to the south of Kyd’s garden house in Shalimar was procured for the purpose.

In an email from London, Richard Axelby of the School of Oriental and African Studies tells The Telegraph, “Supporters of the Empire saw India as a place of wild nature that needed to be ‘tamed’… Through the application of science and better understanding and use of natural resources, India would be ‘improved’ to the benefit of both colonialist and native.” Axelby, a historian, has written a paper titled “Calcutta Botanic Garden and the colonial re-ordering of the Indian environment”.

To return to Kyd, in time he introduced to the garden the nutmeg, the clove, the pepper vine. But it was a failed experiment. He tried to grow tropical fruits such as mangosteen and breadfruit as well as apples and pears from Europe, but this experiment too did not quite succeed. He then turned part of the garden into a teak plantation. Those days teak was used for timber to build ships and was in great demand. The teak plants seemed to thrive but when they were harvested, more than 30 years after Kyd’s death, it was noted that their trunks had hollowed out at the base and were useless. Basically, even in death, Kyd had not lost his touch.

Indeed, at the end of Kyd’s tenure, the garden was not quite the commercial green hotspot it was envisioned to be, but it had more than 300 varieties of plants.

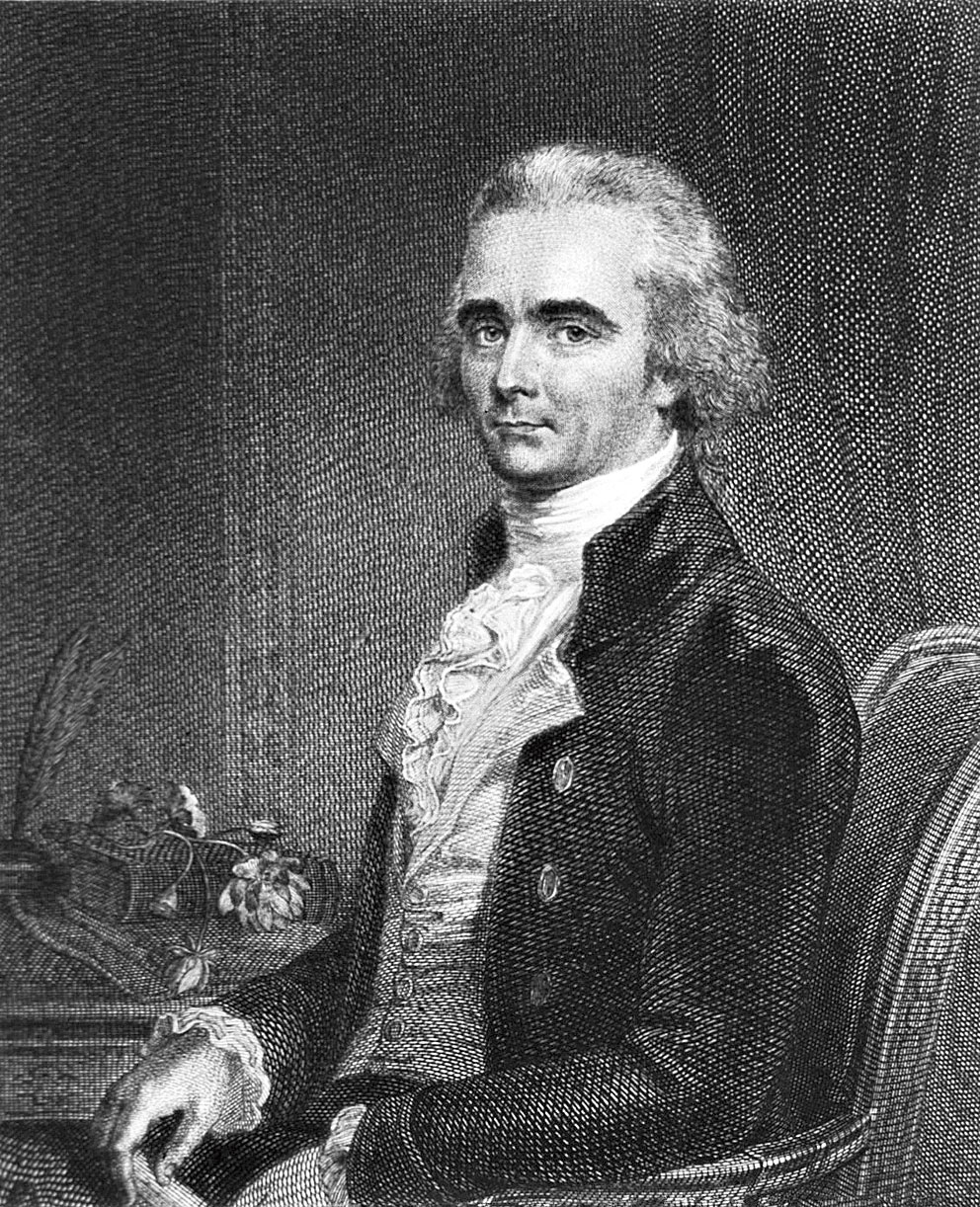

Garden path: William Roxburgh founded a herbarium inside the garden (Wikipedia)

Kyd had never charged the East India Company a penny for his horticultural services. He was succeeded by William Roxburgh, surgeon and botanist, and the first paid superintendent of the botanic garden.

Roxburgh began to collect plants systematically from India, Southeast Asia and the Far East; he set up a herbarium. “Now known as the Central National Herbarium, it is one of the oldest and most extensive in the world,” says Supatra Sen, who is an associate professor of Botany at Calcutta’s Asutosh College. Currently under the Botanical Survey of India (BSI), the herbarium has 2.5 million dried plant specimens, apart from various papers and monographs. “It is possibly one of the largest repositories of knowledge about plant life,” says A.A. Mao, director, BSI.

Basant Kumar Singh of the BSI sums up the transition from Kyd to Roxburgh and thereafter most lucidly. Says Singh, “Kyd was an amateur. It was Roxburgh who shifted the focus of the garden to scientific studies. He studied Indian flora, was the first person to attempt a systematic, scientific classification of the plants here, and he introduced exotic plants to the garden.” Among Roxburgh’s imports were tea, mahogany, rubber, cinchona. He trained a group of Indian artists in the European tradition of botanical drawings. In fact, these nameless painters were responsible for the rise of the famed Company style of painting.

According to Singh, it was the fifth superintendent of the botanic garden, Dutch surgeon Nathaniel Wallich, who was the true heir of Kyd and Roxburgh. He says, “Wallich found the right balance between science and commerce, making the colonists very happy.” Adds Axelby, “The Calcutta Botanic Garden was part of a network of scientific institutions that stretched from Sydney to the West Indies… the botanists of the Calcutta Gardens sought to improve Indian agriculture through the introduction of new food crops and the development of commercial products such as cotton and tea that would stimulate trade and raise the profits of the East India Company.”

Historian Pratik Chakrabarti of Manchester University, UK, points out how the botanic garden was crucial to the introduction of cinchona plantation in Bengal. He says, “There were attempts in 1855 to grow them from saplings in the garden. But this failed due to climatic reasons. The garden along with the Agri-Horticultural Society then advocated cultivation of cinchona on an experimental basis in Darjeeling and the Nilgiris. The large-scale introduction was started in the 1860s under the garden’s supervision.” The bark of the cinchona was used to make quinine then, as it is today — an economical and common cure for malaria.

It was during Wallich’s tenure that the botanic garden became a public pleasure ground. The hammer-shaped garden is divided into 25 divisions — named after all continents and some states of India — and grows 1,400 varieties of plants. Its total green population is 17,000.

But the biggest change of all, as we learn from Singh, is that it can no longer dabble in the exotic. It seems, after many an exotic plant turned invasive, countries agreed to ban import of plant wealth in accordance with the Convention on Biological Diversity, effective since the 1990s.

No Kyd-ing.