Burrabazar is one of the largest wholesale markets of eastern India — textiles, medicines, garments, cosmetics, you name it, you will get it here at bargain prices. Every day, more than 30,000 traders and hawkers work out of this market which extends from the Howrah Bridge in the north to Dalhousie in the south, Strand Road in the west to Chitpore in the east. Every alley is a domain of specialisation.

There’s Phugagalli that stocks balloons and party décor items. Khengrapatti sells knitting needles and electronic goods. Tulapatti has the dry fruit market. Sonapatti is the goldsmiths’ haunt. Chhatagully is lined with shops selling towels and kurtas.

In Burrabazar, it is impossible to say where the pavement ends and the street begins. With its pull-carts and rickshaws, vans and cycles, bhishtis (water carriers) and hawkers, what actually remains of the street is a sliver. Negotiating all of it is akin to walking a tightrope.

Even in early June, once lockdown has been eased, thhelawalas sit on the pavements playing cards, men huddle around tea stalls, sipping laal cha, one or two shops are open. The seths inside the shops are counting wads of notes, their practised fingers flipping currency. Once in a while they lift the finger to the tongue and get on with the counting again. Amidst this mêlée, somewhere stands a staid old hosiery shop, Pratap & Sons.

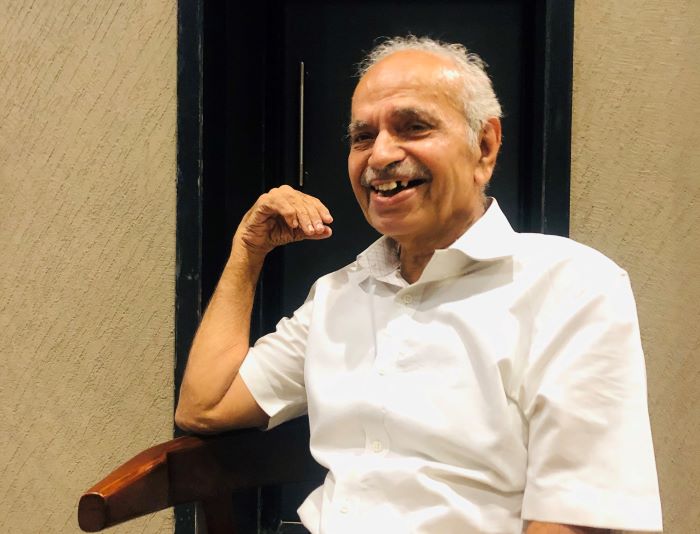

The owner of the shop is Pratap Singh Bhatia. “My middle name is Sinh, which means lion in Gujarati, but when I got my ration card the corporation had spelt it Singh,” he laughs. The octogenarian knows Burrabazar even better than the back of his wizened hand.

Bhatia was born in 1939 in Mundra, a port town in Gujarat. He was two months old when his father, Jairam Narayan, decided to settle down in Calcutta at the urging of his elder brother, who was already based in the city. Says Bhatia, “My father bought a well-stocked hosiery shop on Harrison Road (present-day M.G. Road). He paid Rs 1,600 for it.”

The Bhatias’ address for the next 60 years was a chawl on Mullick Street in Burrabazar. “In the 1930s and 1940s, the rent of a single room was Rs 18.75,” he recalls.

Bhatia’s mind streams the old days in granular detail — names, endearments, events, colours, flavours. “A Punjabi family lived on the terrace. And there was another Lohana Gujarati family (the Bhatias are also Lohana Gujaratis); they still have a shop in Burrabazar. Kunwarji-bapa would tell us religious tales and anecdotes. Every evening around six, we would reserve our spots on the terrace. There was a lot of breeze and it was so pleasant that oftentimes we would sleep there at night. There would be so much fun and laughter. Nowadays, people barely talk to their neighbours but those days...”

He tells me about a Pranjivan-bhai, an Iccha-masi, a Nem-bhai, a Himmat-bhai. The old Muslim dry-fruitwala who had his stall beside the Bhatias’ shop on Harrison Road would offer a teenaged Bhatia mewa whenever he would go to meet him. “I remember, he would always give me a handful of neza (pine nuts), a very expensive dry-fruit, for free. I don’t know if it is still available but those days it used to be more expensive than badam (almonds) and pista (pistachios),” recalls Bhatia.

He talks of a Bhagwandas who lived on the floor above theirs. “He would sell churan for three annas (an anna equals 1/16th of a rupee). He was healthy and sturdy and would wear a white ganjee, or vest, almost always.” It seems one day during the Calcutta Riots of 1946, Bhagwandas ventured outside despite warnings, to what is Bagree Market today. Says Bhatia, “He said he had to go see a friend and he would be careful. After, a while his dead body was brought back home.”

Bhatia studied up to Class X and then dropped out of school. At the age of 17 he joined his father’s business full-time.

In the 1950s, Burrabazar was a veritable mini Gujarat. Bhatia does not know how this came to be, but he is sure of what he is saying. In the early and mid-20th century, apart from the prospering cities of Ahmedabad, Rajkot and Surat, the rural side of Gujarat was underdeveloped. While the working classes eked a living for themselves, those who had businesses to run or dreams of better prospects and a better life migrated to Bombay and Calcutta. The Shahs, Mehtas, Meghanis, Doshis, Kamdars, Patels…

“Those days, every home in every building in the lanes and alleys of Burrabazar had mostly Gujaratis and some Marwaris,” says Bhatia. “As the years rolled on, it started developing into a commercial hub and the houses were turned into offices and godowns. Except for a handful, most Gujarati families moved to either Bhowanipore or Tollygunge, while some others chose Howrah as their new home,” he adds.

According to Bhatia, for the regular Gujarati those days, Burrabazar was Calcutta and Calcutta was Burrabazar. Most children went to the Calcutta Anglo-Gujarati School in Burrabazar. Temples too were at a walking distance for most of them. They sometimes went as far as Esplanade, but never beyond, never visited Park Street. The very Bengali neighbourhood of Sovabazar is mere two kilometres away from Burrabazar, but the only interaction most of them ever had with Bengalis was restricted to matters of trade.

Talk of trade brings us back to the hosiery shop. Bhatia recalls that since the very beginning he had customers of all backgrounds. He says, “In the 1950s, we sold ganjees for Rs 2 and 25 paisa, and now even the cheapest vest is priced at Rs 70.”

Burrabazar for Bhatia will never be about business alone. It is about an appetite for life. And food too was an important part of it.

He talks about the Punjab Chaat House, where he could not finish a plate of chaat that cost two annas. “Those were the days when we would eat 16 phuchkas for Re 1,” he adds with a chuckle. “There was no idliwala in Burrabazar then. One bearded Madrasi started coming to Pollock Street. He would sell one idli wrapped in banana leaf for one anna. It was a new thing for us,” he adds.

He talks of a Surti Hindu Hotel owned by a Gujarati in Sutapatti. “It was a spacious place. We would eat masala aalu and a jalebi for two annas. The seth would sit all day at the cash counter with the ashvageeta. You know what it is, right?” Without waiting for an answer he continues, “There would be horse races every Saturday. And the ashvageeta would have the details. The seth would not even look up at the customers. He would ring a bell and the waiter would shout out the amount to be paid. The seth would take it, return the change, there was no eye-contact whatsoever. The place was very good but I guess it was sold off eventually.”

His favourite memory, however, seems to be of a vendor who would go around the lanes of Burrabazar selling cubes of white butter. Says Bhatia, “For four annas, he would give a small lump sprinkled over with sugar powder. It was so soft that it would melt in the mouth. It is unlike anything you see or have now. Such vendors and experiences do not exist anymore.”

Everything is different — that seems to be Bhatia’s refrain.

He tells me how by 8pm those days, everybody would shut shop. If one was carrying a lot of cash from work to home, one wouldn’t feel scared. “Now, can you even imagine something like that?” he laughs and tells me about an acquaintance who was shot dead on Burrabazar’s Kalakar Street a decade ago.

Bhatia boasts of having seen “Nehruji”, Soviet politicians Nikita Khrushchev and Nikolai Bulganin, the Vietnamese helmsman Ho Chi Minh. He remembers having seen Raj Kapoor and Nargis at Orient Cinema, which is non-existent now, and Rajiv Gandhi at the Satyanarayan Mandir on Kalakar Street.

“Every lane, every chappa and every building around Central Avenue [Chittaranjan Avenue] would be jam-packed. The roads would be shut and there would be tight security all around. But not long ago when the then president, Pranab Mukherjee, was visiting Calcutta, I was asked to leave the Maidan, where I was doing my morning walk. Everything is different now,” he says disapprovingly.

Not just the buildings and the people, he bemoans the changed feel of the roads as well. Earlier, there used to be water hydrants and corporation lampposts. “Around 5 o’clock every evening, a man from the corporation would come with a ladder, climb it, unclasp the glass casing of the gas lamp, light it and go away.”

Bhatia’s son runs the Burrabazar shop now. But the elder has an idea that his grandson will not be interested in the family business. He himself goes to the shop every day for two hours. He tells me, “Everything is different. But darji no dikro, jeeve tyaa sudhi seeve… A tailor’s son must stitch till the end of his life.”