On the eve of World Museum Day — May 18 — in the midst of much heat and dust and a feverish general elections, the first project director of the museum of brooms arrives in Calcutta. In the course of a two-hour talk, Rustom Bharucha, who is also a culture critic and professor of Theatre and Performance Studies at Jawaharlal Nehru University, addresses a small gathering at Victoria Memorial Hall about the museum, Arna Jharna, and Komal Kothari, the man who dreamt it up. Arna Jharna is Hindi for forest spring. The museum bearing the name is located in an abandoned stone quarry in Jodhpur.

Kothari or Komalda, as Bharucha refers to him, was a folklorist. “He wasn’t a folklorist by training,” says Bharucha, “…but there wasn’t a folklorist in the world who would not get in touch with him. He was a touchstone in the field.” The grey-haired late visionary is present that day in spirit and in picture — a life-size photograph stares down at the audience. Among other things, Kothari had documented the folk songs of Rajasthan along with his friend and Rajasthani novelist, the late Vijaydan Detha. Together they had chronicled a repertoire of songs of the tribes of Rajasthan — Langas, Kalbelias, Mangalias, Dholis. By the 1980s, these desert musicians were performing in Carnegie Mellon (US), Kremlin (Russia), Edinburgh (UK), Adelaide (Australia) and other places.

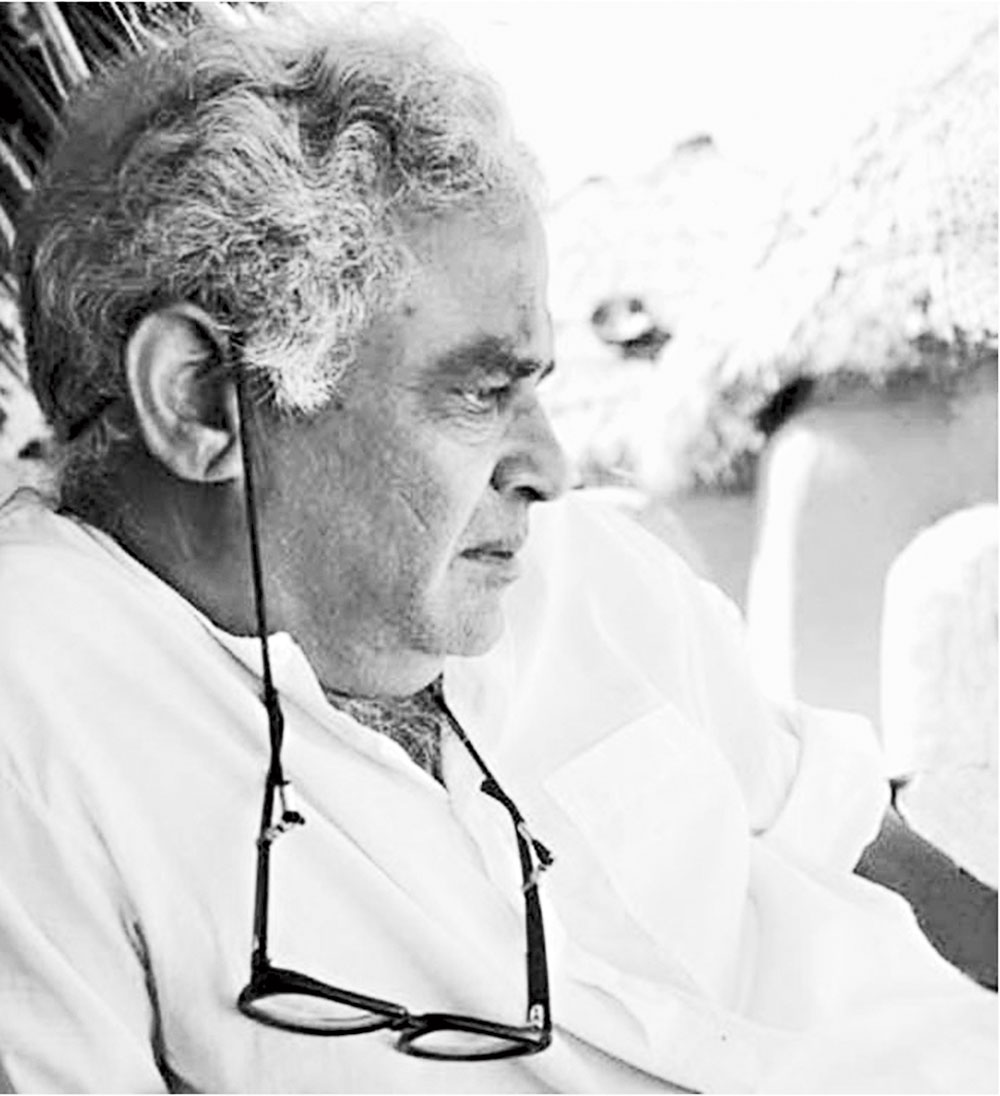

The late Komal Kothari Photograph courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall and Rustom Bharucha

Bit by bit a picture of the man comes into focus. The bearded-bespectacled Bharucha talks about Kothari’s “rhizomatic way of thinking”. He says, “Komalda would talk about zameen and mitti, and then go on to grass, the sewan grass (found in western Rajasthan) that grows up to six or seven feet during the monsoons and is said to cover even the camels walking through them. Sewan grass is to be found in the bajra-growing areas and if one were in the bajra-growing areas, one would hear the ravanahatha [an ancient bowed, stringed instrument] and if you heard the ravanahatha, you would hear the story of Pabuji [a Rathor prince whose heroic narrative is popular in these parts].”

Bharucha met Kothari for the first time in 1986. Thereafter, a conversation started between the two of them that took the shape of a book, Rajasthan: An Oral History. By the time Kothari envisioned the broom museum, he was dying, he had been diagnosed with cancer. “Even then he wanted to build an ethnographic museum and begin with one object, the jhadu,” says Bharucha.

It is difficult to think of a broom as a museum object, yet Bharucha is insistent: “If you pick up something ordinary, something very marginal and give it the same intensity of thought as you would to a sculpture or a painting, a world of ideas can open up.”

Now, out of sheer curiosity one decides to sit through some more of the talk. In the meantime, Bharucha has started to enumerate different kinds of brooms. Brooms made of a type of grass, the pammi, which grows in Uttar Pradesh. Brooms made of date palm fronds and bamboo. Then there is the phuljhadu that is made out of a weed that grows in Mizoram.

The talk now progresses in swift strokes, from material knowhow of brooms to the social mores surrounding them. Never give a bride a broom when she is leaving the house or all your wealth will go. Never use the broom after sundown. Bharucha tells his audience how during the course of his sweeping research he came across a Sufi saint called Jhadu Baba. “He grew up in mounds of garbage and lived there, and people came to him looking for solutions to their problems,” he says.

And then the discussion turns to castes of broom-makers — the Banjaras of Jodhpur, the migrant Kolis. Says Bharucha, “Then there were the self-identified Harijans who had a monopoly over the bamboo brooms, the most expensive of brooms. They are an economically mobile people but that does not translate into social mobility and they are a much stigmatised community.”

A collection of brooms for outdoor spaces Photograph courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall and Rustom Bharucha

Once he has made sure that everyone has been steeped in the broom philosophy, Bharucha describes the physical space that is Arna Jharna. There are three thatched mud huts, two outer structures, a courtyard, and a khejri tree. The red mud walls have the traditional white mandana paintings on them.

The three-module structure of the museum was apparently Kothari’s idea. Bharucha assigned the three spaces of Arna Jharna thus — one to brooms used in outdoor spaces such as courtyards, streets and highways; another to brooms used indoors; and a third kind that is meant for documentation, exhibition and filming. He says, “The principle of the museum is to encourage visitors to pick up the brooms, touch them, use them and then put them back.” Here brooms are docile objects. Bharucha had thought of a more animated display wherein each broom would have an audio recording of its maker telling its story. But there was a problem — most of the broom-makers spoke in local dialects .

A lake created in an abandoned sandstone mine by harvesting rainwater — a resource for villagers and fauna alike Photograph courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall and Rustom Bharucha

The brooms for outdoor spaces are really a collection of twigs tied up with strings. “You can never find these brooms in the market,” says Bharucha. They are made by the womenfolk with whatever material they find around them. The brooms in the Arna Jharna museum have all apparently been gifted by the women who made them. A series of videos highlight the communities, labour, skill and even risks associated with broom production.

Apart from brooms, the museum also has a collection of musical instruments from western India, including popular instruments such as the ravanahatha, Gujratan sarangi, Sindhi sarangi and the surinda, and some that are no longer used or produced, such as the jantar, jogia sarangi and nagfani. Pottery and puppetry are also showcased in Arna Jharna.

The museum with a khejri tree in the foreground Photograph courtesy: Victoria Memorial Hall and Rustom Bharucha

Beyond the three huts are two little outer huts in the museum complex, of which one used to be a shrine. “We wanted to keep it as a shrine but then ran into problems as it would have to be a shrine of one god and not of another,” says Bharucha. So they used the kavad, a portable shrine that opens up with door flaps. The abandoned pit on the land on which the museum came up has turned into a lake — a live demonstration of successful water harvesting. “We are lucky that the area adjoining the museum is forested land. The water of the lake is used by the locals and the birds,” informs Bharucha.

It is difficult to grasp the full import of a broom museum in faraway Rajasthan. And yet, like a desert mirage, the idea seduces before it disappears. An elderly woman in the audience raises her hand — she wants to know if Bengal’s narkel jhanta, a broom made of coconut sticks, has found a place of its own in Arna Jharna.

A broom is a broom is a broom, and as it turns out — way more.