If the lamassu were to be asked where it wanted to go, what would it say? The man asking the question is British Museum director Hartwig Fischer. He is addressing an audience at Calcutta’s Victoria Memorial Hall. The topic of the evening is Building – Destroying, Forgetting – Discovering, Understanding – Healing: Cultural Heritage and the Encyclopaedic Museum.

Fischer continues, “Would it say ‘I want to go back to the quarry because no one had the right to carve me out of stone in the first place’? Or would it say ‘Let me stay underground, I don’t want to see any more destruction’? Or would it simply say it wants to be part of the ever-growing knowledge and reference through our times and cultures and be part of a museum which transcends all borders, one that teaches humankind what it takes to create culture, keep it alive and what it takes to heal?”

A lamassu, it turns out, is a mythological creature — a winged lion or bull with a bearded human head. This antiquity from the neo-Assyrian civilisation of the 10th and 9th century BC, survived the Daesh-led deliberate destruction of the cultural heritage in Iraq since 2014. Daesh is the Arabic language acronym of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

The Assyrian empire grew in the 8th and 7th century BC stretching from West Iran to eastern Mediterranean — covering what is today Iran, Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel, southern Turkey and Egypt. It reached its widest expansion under its last emperor, Ashurbanipal, who ruled between 669 and 631 BC.

Similar lamassus, reliefs and statues, including those in the Mosul museum and at the Nergel Gate, entryway to the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, were not as lucky.

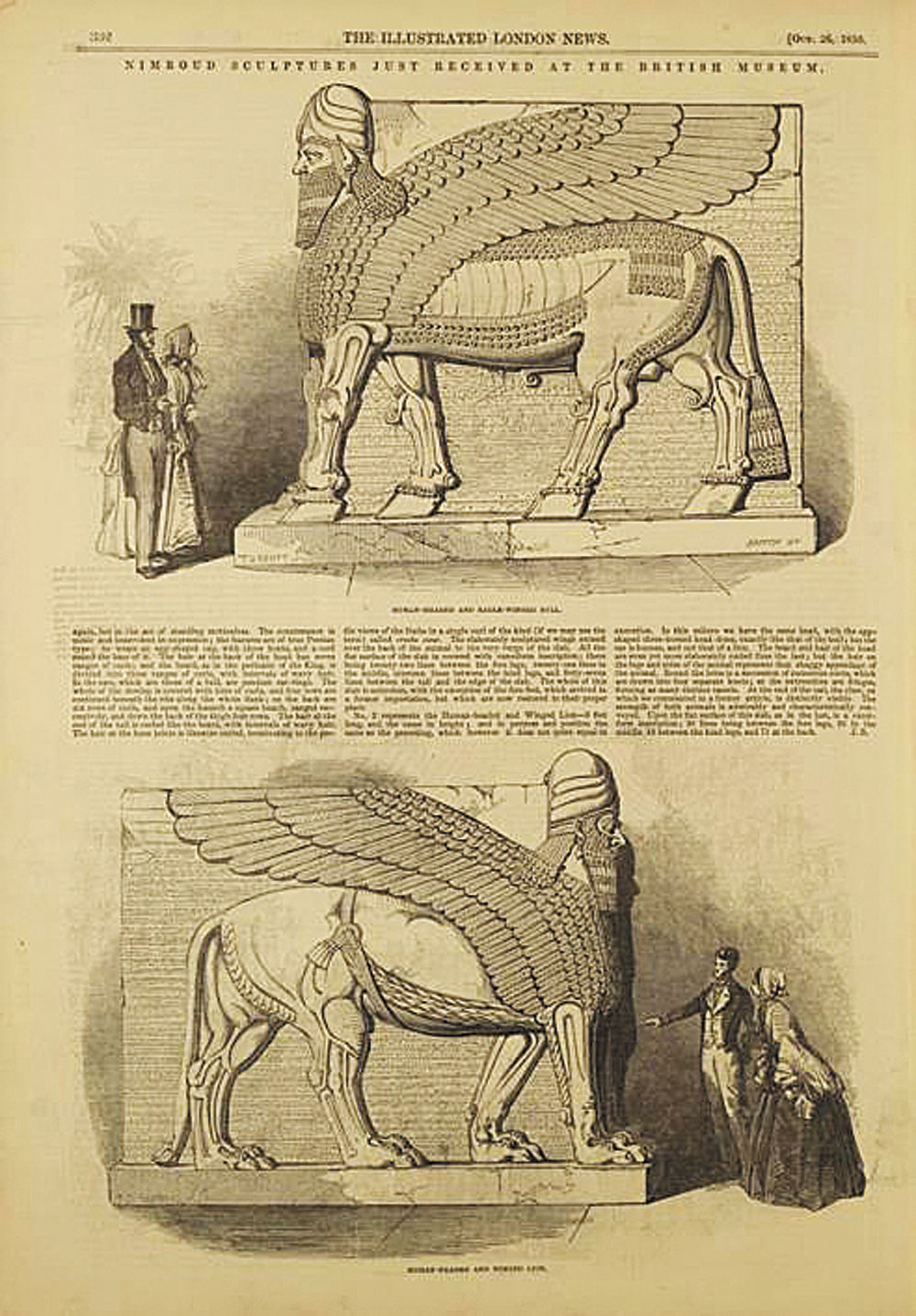

A page from The Illustrated London News showing popular reception of the lamassu at the British Museum Source: British Museum

“This lamassu was discovered by Daesh fighters but they had no time to destroy it,” says Fischer pointing to a slide with a picture of the surviving statue. The 57-year-old talks haltingly and deliberately about the wilful destruction of antiquities, pausing to show his slides that depict the large-scale destruction. His audience, a packed auditorium at the Victoria Memorial Hall on an April afternoon, listens with rapt attention.

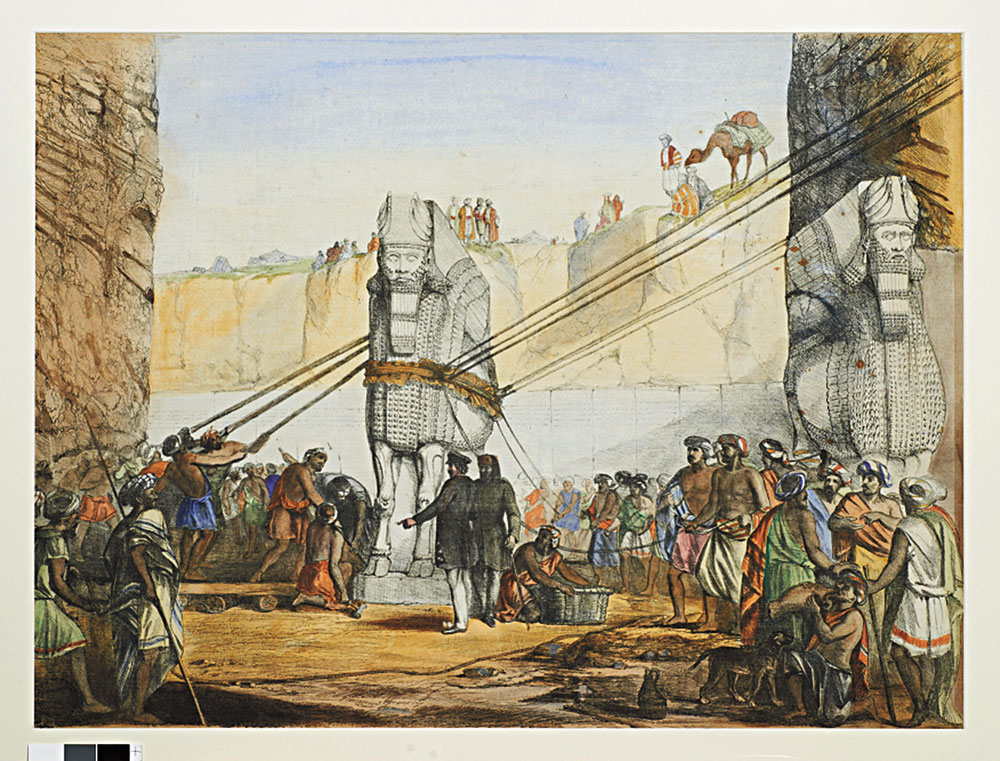

The figure of the lamassu recurs throughout the Assyrian civilisation. These monumental statues or sculptures had to be quarried in faraway regions and then dragged to the shores of the Tigris to be taken upstream to Nineveh, the new capital that Ashurbanipal chose for himself and his government. The transporting work had to be done by the people who had been enslaved.

Lamassus were usually placed at entrances of palaces as protective forces, to protect the ruler from evil and destruction. “This was to impress the visitors to the palace at Nineveh,” says Fischer.

Ashurbanipal had depicted himself as the one who slays the lion. Hartwig tells his audience, “In his relief, you can see a stylus that is stuck in his belt. It is a writing tool. He wanted to be depicted as a man of letters. He knew how to read and write and made sure everybody took note of that.”

It seems the emperor also created the biggest library of his time of Cuneiform tablets, an encyclopaedic library covering all areas of knowledge — medicine, agriculture, trade, astrology, the art of predicting future by reading the liver of a sheep. Cuneiform is a system of writing first developed by the ancient Sumerians of Mesopotamia c. 3500-3000 BC. It is distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, made with a blunt reed for a stylus. The name itself means “wedge-shaped”.

After Ashurbanipal’s death in 631 BC, the Assyrian empire began to disintegrate. In 612 BC, Nineveh was conquered. Thus a great culture sank into the sand. And the only records that remained of it was the Bible and some Roman history texts. It was only in the late 19th century that British and French archaeologists started digging to bring up the ancient cities to roof.

Iraq was severely damaged during the second Iraq War. In 2003, the National Museum of Iraq was plundered. John Curtis, head of the Middle East in the British Museum, went to Baghdad right after the invasion and fall of Baghdad for the first assessment. He tried to salvage whatever he could. “There is a danger to the survival of the cultural heritage in times of conflict,” says Fischer. “This danger is not limited to one zone or one country or region,” he adds.

Commenting on how the iconography of the past was being used by present rulers to justify their ends, Fischer showed two interesting slides — one of a relief of Ashurbanipal killing a lion, and another pictorial representation of a current leader who considered himself a true descendant of Ashurbanipal, doing the same.

“Daesh came into being basically under the leadership of those who served Saddam Hussein and those who had been dismantled and imprisoned and excluded from public life. They used religion to reconquer territory they had lost and to target systematically and damage historical and heritage sites, the past that you can relate to in order to look beyond ideological blinkers that those who seek absolute powers want to force upon you,” says the director of the museum.

A watercolour representation of the lowering of the lamassu Source: British Museum

Damage to cultural heritage by Daesh that started in 2014 in Iraq was immense. About 60 per cent of Nineveh was lost, and 80 per cent of Nimrud, another ancient city. “The very day Daesh crossed the line between Iraq and Syria, they published a hashtag #sykespicotover, which indicates an awareness of the deep and immediate history of the region and their political project of a Caliphate transcending political border,” says Fischer. The Sykes-Picot agreement was a secret 1916 agreement between the United Kingdom and France to which the Russian Empire assented. It defined mutually agreed spheres of influence and control in West Asia. “About 813 sculptures and statues were damaged, a library was burnt and the National Museum of Iraq was bombed,” says Fischer.

In 2016, the British Museum launched the Iraq Training Scheme funded by the British government. Two scholars from Iraq are trained at the museum for three months, go back to Iraq and join archaeologists from the British Museum at excavation sites at Darband-i Rania in the north, and Tello in the south.

“This has enabled a number of colleagues from Iraq to survey the sites and save what can be saved. Eight women from Mosul trained in the British Museum and excavated the first bridge and a temple in south Iraq from 2400 BC,” says Fischer.

Returning to his question of where the lamassu would rather be, one cannot help but wonder if it would prefer to remain in the reconstructed palaces of Nineveh, under the nurture and care of modern Iraqis who are the rightful heirs of these priceless artefacts.