Bani adam a’za-ye yekdigar-and/ke dar afarin-aš zeyek gowhar-and. All human beings are members of one frame, or body/Since all, at first, from the same essence came/When life and time hurt a limb/Other limbs will not be at ease/ You who is not sad for the suffering of others/Might not deserve to be called human.”

The portals of the Iran Society, a 75-year-old centre for Persian studies in Calcutta, reverberated with the musical rendition of verses one afternoon. The recitation of 13th-century poet Saadi Shirazi’s verse by Persian teacher Abid Hossain leaves a delegation from Tajikistan speechless.

Tajikistan is one of the central Asian countries where Persian is spoken and used officially, the others being Iran (earlier Persia), Iraq, Afghanistan, Ujbekistan and Azerbaijan. The Tajik delegates, a team of five experts, have been collecting samples of Persian literature, especially poetry, from across the world. “We didn’t know that this region, so far away from the Persian Gulf, had once been a seat of Persian literary activities. We knew about Delhi, Kashmir, Punjab, but not of Calcutta, Dhaka or Chittagong,” says Abdughani Mamadazimov, who teaches international relations at the Tajik State University in Dushanbe and is the leader of this delegation.

Persian or Farsi was introduced in the Indian subcontinent by the Persianate rulers of Central Asia in the 13th century. The language was not only the lingua franca of the classes — just like English in modern India — but also the language of creative literature and philosophy. In fact, the word Hindu, connoting people living in a geographical region beyond River Indus, is of Persian origin. So is the word Hindavi (later Hindi), used for the language spoken by the people in large parts this land. After having played a key role in communication and literature, the language was replaced by English in late 19th century. And now it faces ignominy or oblivion.

During the Muslim conquest of Persia in the mid-7th century, the Parsis took refuge in Gujarat and parts of western India to avoid religious persecution. And that is how Farsi floated into India. “Persian language, with pre-historic roots in southwestern Iran, is one of the oldest Indo-European languages,” says Amit Dey, a senior historian and professor at Calcutta University. He continues, “The Arabs conquered Persia but failed to impose Arabic on the conquered. The Persians were forced to accept the Arabic script but did not sacrifice their language. Instead, Farsi turned into a prestigious cultural language in various empires in Western Asia, Central Asia and South Asia. New literature, espe-cially Farsi poetry, developed as a court tradition in the eastern empires. Thus, Farsi became a vehicle of cultural conquest defying Arabic political hegemony.”

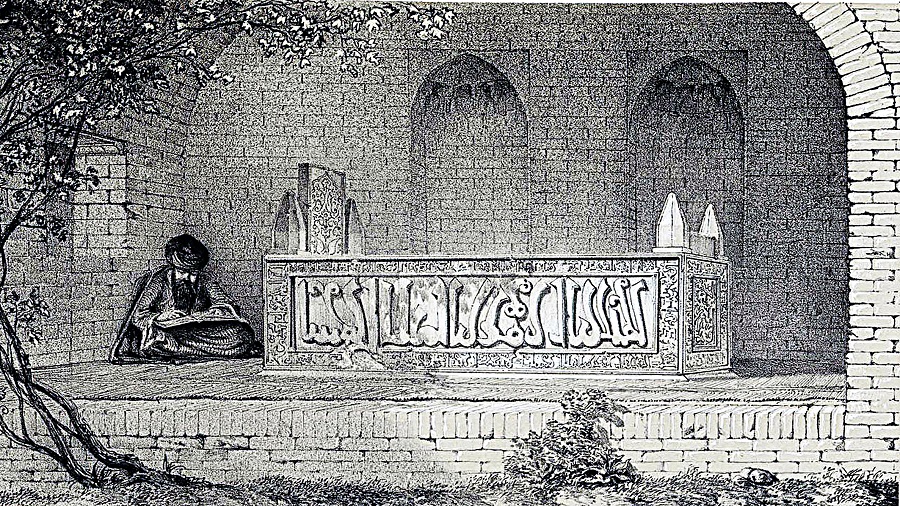

As a result, some of the classics of literature, such as Rumi’s Mathnawi, Firdausi’s Shah Nama, Omar Khaiyyam’s Rubaiyat, Hafez’s Divan and Saadi Shirazi’s Gulistan, were written in Farsi in the medieval period. Farsi also became the vehicle of Sufi mysticism, defying all orthodox religious boundaries.

Its secular, liberal and strong cultural moorings helped Farsi survive political threats from Arabic and other languages. Even rulers of Turko-Afghan origin in medieval India, including those of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal regime, accepted it as the language of the court and diplomatic discourse. “They chose Farsi rather than their mother tongue Turkish, or Arabic. Persian flourished in the Indian subcontinent, unlike in northern Africa where the conquered nations were Arabised,” says Dey.

According to him, the decision to embrace Farsi was actually a political move by the rulers to get the better of the orthodox ulemas or Muslim theocrats — mostly proponents of Arabic and Turkic.

Patronage of the language encouraged the flow of Persian texts and Persian speakers — soldiers, merchants, administrators, scholars, poets, Sufi saints, artists and artisans — to South Asia between the 11th and 18th centuries.

Irrespective of their ethnic, religious or geographical origin, these migrants from central and western Asia had skills in Farsi that would help them earn a livelihood in courts and bureaucracy.

Farsi reached its pinnacle in south Asia when Mughal emperor Akbar established it as the official or state language in 1582.

Mind you, this was despite the fact that the Mughals were native speakers of Chagatai Turkic. “He used the language as a tool to knit together diverse religious and ethnic communities in his court as well as his burgeoning kingdom, culturally,” adds Dey.

Not just Muslim aristrocrats, but also scribes of upper caste Hindu lineage — Brahmins, Kayasthas and Khatris — who served as clerks, secretaries and bureaucrats, learnt the language and got acculturated in Persian etiquette for social mobility. Ghazals, nazms and qawwalis (at Sufi shrines) in Farsi were wholeheartedly accepted as forms of literary and musical expression by the educated of all faiths and ethnicity.

Akbar and Jahangir commissioned Persian translations of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Dara Shikoh went a step further when he took up the task of translating the Upanishads into Persian, aided by veteran bureaucrat Chander Bhan. Persian romances, such as Laila Majnu and Yusuf Zuleika, were translated into many Indian languages.

The medieval Bahamani Sultanates and successor Deccan Sultanates and even the Hindu Vijayanagara kingdom had highly Persianised culture. The Sikh gurus as well as the Maratha ruler Shivaji were well-versed in Persian. The language had been used by the Bengal Sultanate as one of the court languages and in the chancery’s administration mainly in urban centres in Gaur, Pandua (today’s Malda), Satgaon (a port in Hooghly) and Sonargaon (near Dhaka), long before the Mughal period.

One of the principal patrons of Farsi in the early 15th century Bengal was Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah who established contact with the legendary Persian poet, Hafiz. Poet Alaol composed literature in the language and translated Persian classics into Bengali.

Royal patronage encouraged a section of non-Muslim elites in Bengal, especially the Bengali Hindu gentry and aristocracy, appropriate aspects of Persian culture, such as dress, social practices and literary taste. Rammohun Roy wrote treatises in Persian and started India’s first Persian newspaper Mirat-ul-Akhbar in 1823. The country’s first Persian printing press was also set up in Calcutta.

In the initial phase of the British administration, Persian was used as the language of the courts, correspondence and record-keeping. Governor-General Warren Hastings, well versed in the language, founded the Calcutta Madrasa where Persian, Arabic and Islamic Law were taught. The remnants of Persian judicial terms adalat, mujrim, munsif and peshkar are still used in courts across India.

The sharp decline of Persian began when English was made the language of governance through Lord Macaulay’s education policy in 1835. The emergence of vernacular languages, especially Urdu, ushered in further decay of Persian.

Says Dey, “Persian was, after all, a language of the elite. Urdu first emerged as the common language of soldiers of heterogeneous origin (Mughals, Rajputs, Pathans, Turks, Iranians, etc.) in the Mughal camp, and then became a language of the masses.” Urdu borrowed elements from Persian — idioms, styles, syntax, script — and mixed these with the local dialects, such as Poorvi and Brajbhasha. “Sufi saints like Nizamuddin Aulia also chose Urdu for discourse with his followers,” he adds. Furthermore, many madrasas started focusing on religious education with more emphasis on Arabic scriptures.

Notwithstanding its decay, Farsi survives in Hindi and Bengali as thousands of loan words used in everyday life. Sample these: abohawa (weather), jomi/zamin (land), maidan (ground), rang (colour), maja (fun), kalam (pen), chashma (spectacles), pyaz (onion), pulao (flavoured rice), jharu (broom), badmash (rogue) and so on.

It also survives as a discipline in “foreign language” departments of many universities in Calcutta, Delhi, Mumbai, Lucknow, Hyderabad, Guwahati and Patna. Says Iftekhar Ahmed, head of the department of Persian in Calcutta’s Maulana Azad College, “There are plenty of jobs for students of Persian in Central Asia and the Middle East. Some of the graduates are even hired by giant tech companies such as Amazon and Google.” Institutes like the Indian Institute of Persian Studies, Delhi, and Calcutta’s Iran Society are trying to keep the language and its heritage alive.

The Iran Society, founded by M. Ishaque, a Persian scholar, is the country’s oldest functioning centre for Persian studies.

The society offers a Farsi course and is a treasure trove of old and rare Persian books and journals. Fuad Halim, a council member of the society, says, “Most of our students are researchers of medieval Indian history, which is primarily documented in Persian. But there are some retired people too who join the course just for the sake of learning.”

Pritam Goswami and Prateeti Bhattacharya are two such PhD scholars. Pritam is researching the evolution of food habits of Bengalis which include food of the Nawabs of Murshidabad and Dhaka. Prateeti is working on the position of women in the Delhi Sultanate. She says, “Since there is a lot of misconception and misrepresentation of the history of the period, I want to read the original documents and treatises penned in Farsi.” Subhashini Majumder is a retired state land revenue officer who joined the course because she wants to read Rumi and Saadi in Persian.

The institute has been serving as a window to the Persian world hidden in the heart of the city. While visiting the institute at Kyd Street (now known as Dr Md Ishaque Road), Tajik scholar Abdughani expresses hope that the institute and the language can “build a bridge between secular Indians and secular central Asian nations.”

According to him, Persian is a language that has defied all borders and divisions. He adds, “It’s a neutral language of poetry, philosophy and culture that has united political and sectarian divisions for thousands of years.”