They chanted to keep the jwara at bay — Nah samvidvan pari vrimddhi takmana. Meaning, O fever, listen to our prayers and spare us! The sages and their chant belong to the Atharva Veda, the ancient treatise on everyday living most likely composed between 1000 BC and 900 BC.

According to Indologist Sucheta Bandyopadhyay, there are references to what we have lately learnt to recognise and fear as the pandemic in more than one ancient Indian text. Bandyopadhyay has been working as an Indological researcher at Calcutta’s Netaji Institute for Asian Studies for the past 10 years. She is also a student of Sanskrit scholar and Indologist Nrisinha Prasad Bhaduri.

Of course, what is called takmana in the Atharva Veda, reappears as jwara in the Mahabharata and the Puranas, and as mari, mahamari and maraka in later texts such as Kamandakiya Nitisara, Markandeya Purana and Brahma Purana.

These could mean a variety of ailments from malaria to typhoid to tuberculosis or sometimes just a fever. Says Bandyopadhyay, “But jwara is cited as the most feared disease of all.”

Why such fear of the simple fever? Because an infectious fever caused by unknown reasons was regarded as a potential epidemic, she proffers and proceeds to recount a story from the Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata. Here, Shiva destroys the yajna of Prajapati Daksha, and his anger and sweat give birth to a man who is radiant like the fire god while possessed of the power to destroy all like Shiva himself.

This newborn is named Jwara.

In the Vayu Purana and Skanda Purana, jwara is used in this sense, as a mythical persona. In the words of Vyasa, jwara other than fever connotes destruction or death. So, erosion of rocks is described as the fever of the mountain, alkaline soil is believed to be fever of agricultural land — parvatanam shilajatu/usharam prithivitale. In the Garuda Purana, jwara is equated to the king of diseases, similar to the lord of death — jwaro rogapatih papma mrityurajo ashanantaka. This particular Purana also contains the notion of quarantine; it talks of a period of seven, nine, 11 or 14 days that is crucial for anyone suffering from jwara — dwiguna saptami ya cha navamyekadashi tatha.

The Garuda Purana, while analysing various types and symptoms of fever, says it is mainly caused by santapa atmapacharaja or unhygienic habits. Jwarah kalam dirghmapyatra bartate/krishanam byadhiyuktanam mithyaharadisevinam, directs this ancient treatise. Meaning — a good and healthy diet as prescribed by the physician is necessary to fight the jwara and a poor diet can be the cause of slow recovery.

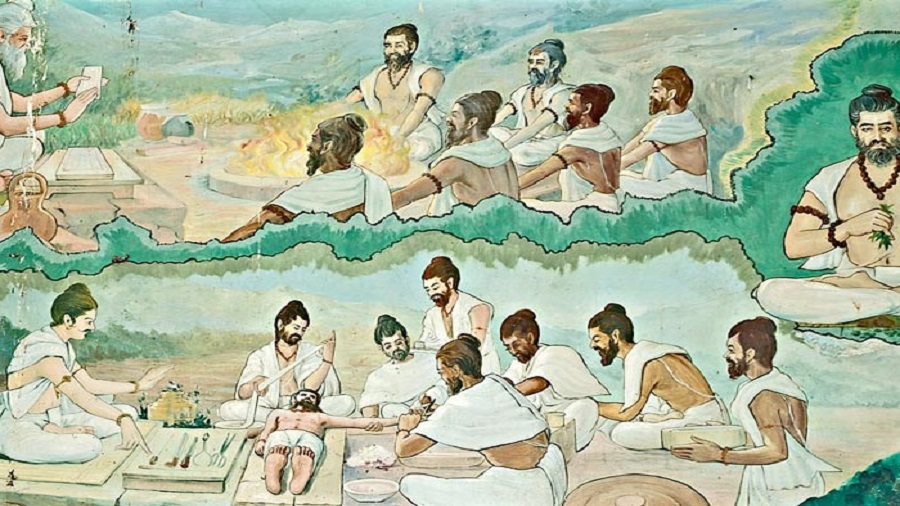

Part of Sushruta Samhita, an ancient treatise on medicine and surgery, written on palm leaves by Sushruta Wikimedia

The ancient texts, by and large regard epidemics as daiva or destiny. At times, it is also explained as karmaphala, or the fruit of misdeed, of a tyrant king. Akaryam Nahushakarshilapsyam stvatkrite vyatham/Shatanchaikancha roganam sarvabhuteshvapatayan read these lines from the Mahabharata. Translation, the sins of King Nahusha gave birth to a hundred and one diseases.

Nahusha is an example of a good king gone rogue. He misused his divine powers, tortured his people and the wise men of his kingdom, abused the women and neglected the children. Difficult to say if this is epidemiology or morality, but the ancient texts would have us believe that the virtuous kings — Dasharatha, Rama, Prithu, Mandhata — had no fear of the fever-inducing virus.

In one chapter of Arthashastra, Chanakya discusses how to deal with an epidemic. In the same chapter, he discusses the tackling of famines, floods and other disasters. “Apart from the spiritual activities, according to Chanakya, it is the duty of a king or the government to take care of the poor citizens and help them by supplying food and other necessary things at the time of epidemic,” says Bandyopadhyay.

The medical aspect of jwara is dealt with in the Charaka and Sushruta samhitas. Charaka, who was a renowned physician, used the word janapadadhwamsa as synonym for epidemic.

It is he who recommends both medication and the panchkarma or the five-fold purification for patients. The panchkarma, which literally means five things to do, involve vamana (induced vomiting), virechana (purgation), kashaya vasti and sneha vasti (two kinds of medicated enemas) and nasya (nasal medication). This therapy for 14 to 28 days with proper medicines and a healthy diet can cure any kind of jwara, according to Charaka.

Says Bandyopadhyay, “Charaka Samhita has a chapter on epidemics written in prose wherein causes of epidemics and the recommended line of treatment are discussed. It says unsalutary wind — vata evamvidha anarogyakara — such as unseasonal, extremely hot or cold, violently blowing, excessively humid or dry wind can cause epidemics. Even air pollution is a cause. Polluted water (udakam tu khalu ityartha vikritagandha-varna-rasa-sparsha), unnatural changes in season, and a dirty and polluted country (desham punah prakritivikritavarna-gandha-rasa-sparsha), and unhygienic lifestyles lead to epidemic.”

As the world keeps on searching for medicines and vaccines to rid itself of the deadly virus, Charaka’s advice appears relevant. The ancient physician said throughout the year, doctors should keep on searching and examining medicinal herbs and their effects on the human body, so those could be utilised during such medical exigencies.

Mind you, there’s no reference to drinking cow urine.