Sometimes, when I turn the page of a book or stand in queue to vote or order online on the spur something I want to eat, I imagine their gaze upon me — amused, interested, always kindred. Them, as in all those women before me with their untold struggles — much of it unresolved in their own lifetime. Them, who have led me and so many others up to this point in history.

The cover of Uma Bhattacharya’s Bengali book Shei Meyera or Those Women published by Joydhak looks like a rain of spoons and ladles. There is a strap running along the bottom with tiny sketches of women; one of them with a sword raised. No, she is not the Rani of Jhansi but an Everywoman from her regiment, Durgavahini. Not too many people would be acquainted with her — Jhalkari Bai of Bundelkhand — but there she is on the cover, one hand raised in exclamation, drawing attention to her lesser-known ilk. Bhattacharya’s dedication reads: “Those lives that light hope…12 stories of such women I gift to all the women of Bengal”.

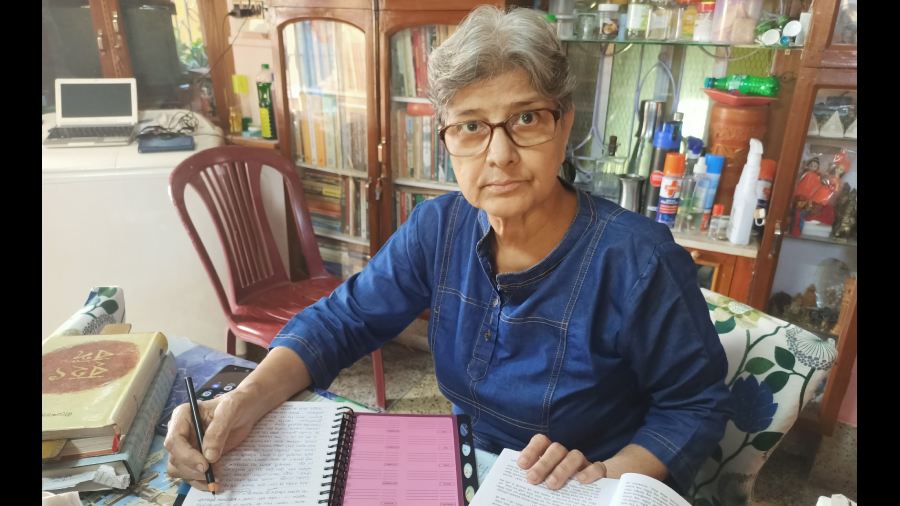

As a little girl, Bhattacharya had been “blown away” by physicist-chemist Marie Curie’s story. As life happened, through the untimely death of her father, her own interrupted university education, responsibilities towards four younger siblings, her job at the state health department administering vaccines and inoculation to children, marriage, motherhood, the life-changing and long drawn ailment of her husband and more, the radioactive Curie continued to glow in one corner of Bhattacharya’s subconscious.

She taught in a primary school in Bengal’s Naihati for three decades. Life turned a corner, the children grew up and settled down, retirement drew closer, Bhattacharya signed up for computer classes, photography lessons, started to travel. She talks about how she found herself thinking about women, the responsibilities they shoulder untutored and yet, the many opportunities in education and self-improvement denied to them by society. Says the 71-year-old, “Was there never any one or more women who managed to get the education they deserved and hankered for? I started looking for stories.”

Bhattacharya’s starting point was Dinesh Chandra Sen’s 1935 book Brihat Banga or Greater Bengal: A Social History. In its pages she met Hoti and Hotu.

Hoti was born around 1740 and Hotu two decades later. Both belonged to what is present-day East Burdwan district. Both became educators and in time, earned the title of vidyalankar or one whose ornament is learning.

Bhattacharya was hooked. She wanted to know more but information was hard to come by. Around this time, she was working on the history of Naihati and that is how she landed up in Garifa where one branch of (19th century philosopher and social reformer) Keshab Sen’s family lived. From them Bhattacharya learned about Nagendrabala Debi.

Around the time of Gandhi’s Non-cooperation Movement (1920-22), Nagendrabala had started teaching the women of Garifa how to work at the charkha, she started a night school for them, she gave them lessons in midwifery. Says Bhattacharya, “I learnt all this from her grandson Diptimoy Ray. He showed me her letters and diary. He also showed me her charkha.”

In December of 1929 at the Lahore session of the Congress, Nehru proclaimed Purna Swaraj; there was a nationwide call to observe January 26 as Independence Day. Naihati responded. A flag was hoisted on the grounds adjoining Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s homestead. Among those who congregated not caring for the police’s lathi was Nagendrabala along with her minor son and daughter.

“Do you know who Nagendrabala’s elder daughter grew up to be,” Bhattacharya asks. And suddenly I am in the middle of another woman’s story. Santosh Kumari Gupta was a trade unionist — she worked in the jute belt and built the Gouripur Workers’ Union — in the 1920s. Santosh Kumari was also editor of the journal Sramik, which some say was the first journal in Bengali to discuss class struggle and socialism.

Buoyed by her findings, but still looking for Hoti and Hotu, Bhattacharya started reading the history of Hooghly and Nadia. She learnt about Drubomoyi Debi who lived in Beraberi village close to Krishnagar in the mid-1800s. She says, “By the time she was 14, she had mastered vyakaran (Sanskrit grammar), kavya (poetry), nyayshastra (logic).” Bhattacharya adds, “I learnt about another woman who worked in a crematorium for a living, also in the late 18th century.”

Bhattacharya says she wouldn’t have been persuaded to write these stories had it not been for Hoti. She read the history of Burdwan and the first volume of Sangbadpatre Sekaler Katha (1818-1830). She looked through the shelves of local libraries — Khardah district library and Keshab Pathaghar. She says, “ I wanted to make sure that Hoti actually existed. And I finally found proof in the missionary William Ward’s Account of the Writings, Religions and Manners of the Hindoos.”

Ward, who died in Serampore in 1823, writes, “…there is a female philosopher at Benaras whose name is Hoti Vidyalankar. She was born in Bengal, her father was a Kulin Brahmin, her husband was also a Kulin…” As was common of her caste, even after marriage Hoti continued to live in her father’s house. A teacher himself, he gave her an education and she went on to start her own Sanskrit tol or school. But once her husband died and also her father, Hoti fell into distress. Post the famine of 1770, she lost her students and amid growing fear of persecution by Brahmin pundits she left for Kashi or Benaras.

Uma Bhattacharya

“Here she pursued learning afresh… smritishastra and other shastras,” notes Ward. Bhattacharya went to Benaras and learnt more. How Hoti dressed like a man, shaved her head and kept a tiki or shikha, attended vicharsabhas with the male pundits and even accepted a fee at the end of it like them.

As for Hotu, in those days, her father sent her to her guru’s home in a neighbouring village for formal education. She opened her own school and chose not to marry. Especially well-versed in medical science, many a practitioner of ayurveda consulted her. Bhattacharya found references to her in the journals of the Calcutta School-Book Society, an organisation from the days of the British Raj.

By some accounts, Hotu was born Rupamanjari. Having arrived after her mother lost more than one child, in keeping with customs and superstitions of the time, her mother and grandmother called her Hotu, an endearing derivative of the Bengali word “hat” meaning go away or get out of the way.

Bhattacharya continues to collect women’s histories. Kamala Sohonie the biochemist who was initially refused admission to the Indian Institute of Science by C.V. Raman, freedom fighter Nanibala Debi who did jail time in Benaras where police routinely rubbed chilli paste on her, Sylhet’s daughter Kamala Bhattacharya, Emperor Babur’s daughter and author of Humayun-Nama Gulbadan Begum…

Sometimes, when I cross a street, sing a song aloud, wear what I like and say what I think, I feel a surge of gratitude towards them — shei meyera.