Daughter Number Eight

Goodness me. I can’t work properly today. I don’t know the best way to do all this. I’m panicking. My heart is pounding uncontrollably. I have to get dinner ready quickly. I can smell the meat — it smells as though it’s cooked enough. Oh, I so feel like eating it. When the fast breaks I will definitely be eating some meat. May God accept my fast and bless me with a son this time. What else would I ask for? It’s lucky that I cooked the okra and eggplant last night. That makes my life easier now. Two dishes are ready. They will just need warming up later.

I can hear loud voices from the next room. My mother-in-law and sisters-in-law are laughing and talking loudly. What are they talking about, I wonder? God knows where Sharifa and Nazanin are. I am now eight months pregnant, and I haven’t been for a single check-up. I feel that this one may be a son, but I am scared that something will happen to me. I hear a sweet voice. Who might this person be? It is my third daughter, Basmeena. She has got the salad plates ready for me. Oh, I love her tiny hands. She melts my heart with these little things she does to help me…

Today is my third day in the hospital. I am breathing in the smells around me. One of my hands is connected to the drip. A white sheet is covering my body. A nurse comes in and scolds the women — those women in labour whose babies haven’t yet arrived. If the women scream in pain, the nurses tell them off. There is pain in each woman’s eyes. One is beside me, breastfeeding her newborn baby. I look at the baby and remember my own. I call the nurse and ask, “Where is my baby?”

The nurse, who is wearing pink lipstick, stands over my head. She takes out my file, looks at me very carefully, and leaves without saying anything. After half an hour she is back, and I ask her the same question again.

The Late Shift

It was 1985. The opposition was busy fighting the Afghan army, firing rockets and targeting government buildings and institutions. People used to call them blind rockets because only one in a hundred would hit its target.

Sanga’s heart was beating hard and fast. She hadn’t kissed her two-year-old son goodbye, because when she did, Ghamai would cry and insist on going with her. She couldn’t take him to work, so she usually left the house without letting him know.

Maryam spoke angrily now. “What kind of country is this? They can’t let us live peacefully — how can we live and work in such a situation?”…

One of the drivers told Sanga to get in the car quickly. As soon as she was in, the driver sped towards the Third Macroyan, the residential blocks built by the Russians in the 1950s and 60s. Before the car had reached the first roundabout, a rocket landed in front of them. Sanga’s heart started beating fast. She could hear the screams of men, women and children. There was panic and chaos all around. She promised herself that, if she reached home safely, this time she would quit the presenting job.

She had decided to quit a few times before, but each time that she had thought it over, she had concluded that a life without work would be hard. That thought seemed as bad as death to her.

As they approached the second roundabout, another rocket landed near them. It went past the car and landed on the edge of the roundabout. The driver and Sanga both ducked. Scared and panicking, the driver nearly lost control of the car. He stopped briefly, then set off again.

Now the car had entered her part of the Macroyan area. Along the way, they heard wounded people screaming and calling for help, but no one ran to help them.

I Don’t Have the Flying Wings

I place the mirror against the case and focus it on the roundness of my face. I pull the little stick from the kohl box and run it over my eyelids, turning them dark. Inside the box, there is also a lipstick with no lid, turquoise in colour around the edges, as if it were withering. I apply a little to my thin lips and then, with the tip of my finger, spread the colour around. I see my mother’s wine-coloured beret with its soft loom-beading. I put it on. Then I put on her white shawl with its golden edges, which she has so neatly folded away.

It spreads softly around my shoulders. The tickling feeling, which had waned a little, returns to my body. I look in the mirror and I am a beautiful young woman.

I clap my hands together, and then I start on one foot — leaping and circling. I dance, my hands resting on my waist. I stab the ground softly. I dance on the tip of my toes with grace and delicacy, just like any other girl. I feel as if all the boys are kneeling in a circle around me, clapping for me as I make the other girls jealous. Whenever I stamp my feet on the ground, the dust rises up into the faces of the smiling boys. And I feel shy. As I dance, I look upwards. I see the sky and I see the clouds in blue and white. The hem of the shawl touches my face and the sweat feels warmer around my body. I sense the sound of the tambur in my ears — the sound for which young fingers would give their lives. I dance as if I have been liberated from my body. Despite the heat of my skin, my liberty keeps me cool. I admire my own beauty. I open my thin lips, ready to sing out the poem that has always rested in my throat.

It is at this precise moment that I feel someone watching me. I turn around and my father shouts out my name. I pull the shawl from my head and toss it away. I feel heavy. The colours have gone; the smells are different. His eyes have turned red — bright red and smoky. He seems suddenly to have aged. He is pale, furious.

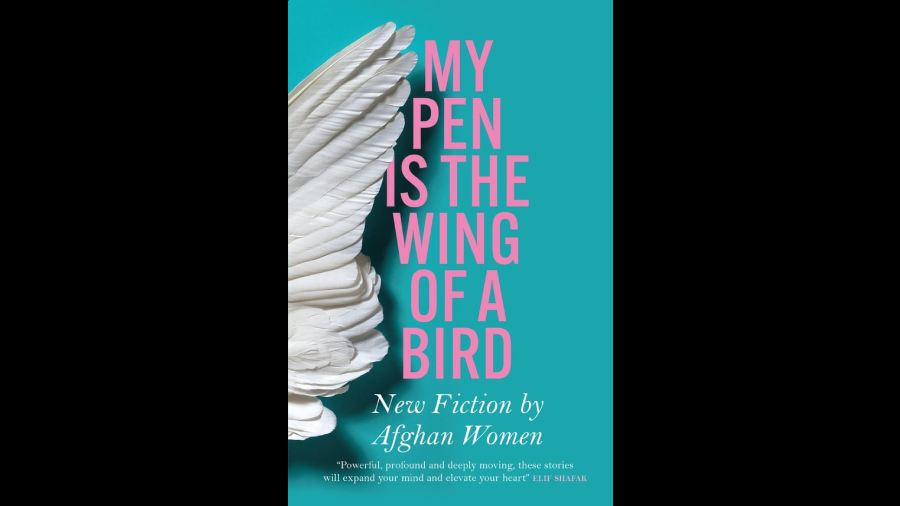

Extracted with permission from My Pen Is The Wing Of A Bird; Published by Hachette