Book: SPEAKING WITH NATURE : THE ORIGINS OF INDIAN ENVIRONMENTALISM

Author: Ramachandra Guha

Published by: Fourth Estate

Price: Rs 799

According to the Oxford Dictionary, a ‘conscientious objector’ is a person who refuses to serve in the armed forces for moral reasons. It became popular during the two World Wars but gained real momentum during the Vietnam war. Most countries do not have compulsory drafting these days; hence protests against wars (especially those that are happening elsewhere) do not amount to jail time as frequently as they did when refusing to go to war was seen as a serious unpatriotic act. Probably, in our time, the biggest conscientious objectors are those who refuse to participate in the onslaught against nature.

Capitalism, riding on relentless accumulation and unthinking consumption over the last two centuries, has brought us to a situation where, in the capital city of our country, rich people are queuing in front of oxygen bars instead of alcohol joints in the chilly evenings of December.

In his lyrically titled latest book, Ramachandra Guha talks about ten such conscientious objectors who cautioned us long ago that this might be our future as a species — hurtling towards a disaster that would not only end our time on this planet but destroy all other life forms that helped us sustain all this while. It will be a mistake to think of Speaking with Nature as a mere cautionary tale. For it reveals more about our chequered pasts — the unreasonableness, carelessness and follies that became our destiny — than any of the recent books I have read. Guha presents this

book as an intellectual history of environmental thinking in India but it is also a solid work of political and social history in terms of the range and the resonance of his observations.

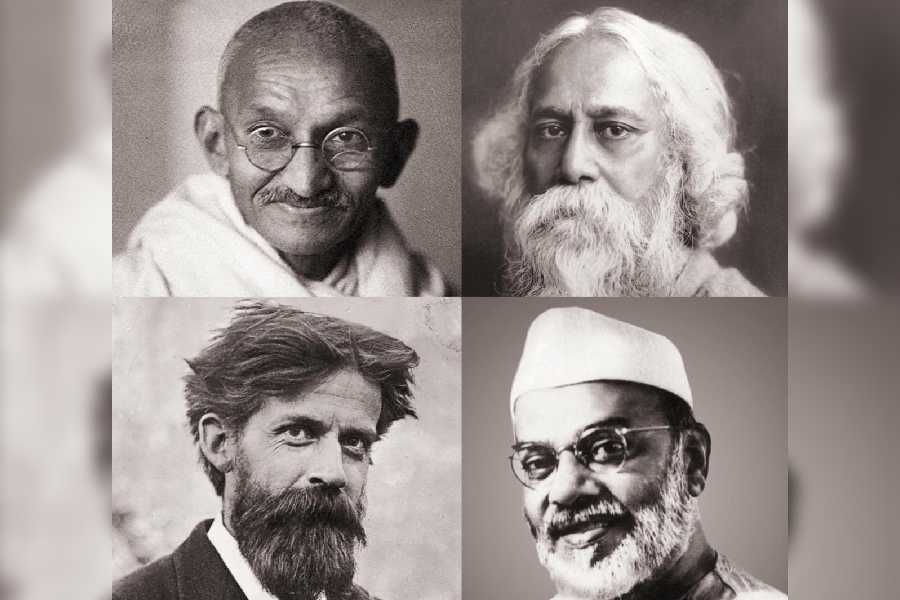

The list of thinkers includes some obvious names like Verrier Elwin, Rabindranath Tagore and M. Krishnan but also some not-so-obvious ones like Radhakamal Mukerjee, Patrick Geddes and J.C. Kumarappa. It pays homage to the almost forgotten and the otherwise celebrated almost equally. The Indian connection of Albert and Gabrielle Howard, the pioneers of organic farming, will be news to many, and the uncomfortable Hindutva lineage of policies of afforestation will be a matter of concern, but the best thing about this book is what it tells us about our collective amnesia. This is not only coming from the lack of attention to or empathy for our surroundings but also the way the post-colonial State inherited some of the worst features of its colonial precursor, namely, the obsession with capital-intensive industrialisation, big infrastructure, unqualified regimes of private property, centralisation of power and absolute disregard for social inequalities. Guha has always been one of the biggest champions of environmentalism-from-below. This book also gives us a clue to how he has organised his thoughts and honed his arguments over the years.

Mahatma Gandhi, though not discussed in as much detail as in Guha’s other seminal works, is the soul of the book. Kumarappa and Madeleine Slade (Mira Behn) were Gandhi’s direct associates and Tagore was one of his closest friends. Geddes and Elwin were in correspondence with him in various stages of their lives. Mukerjee’s ideas of communitarianism and sharing of resources draw on shared concerns. The overtly critical tone that they maintained against industrial capitalism had a legacy in some of the early anti-capitalist imaginaries popularised in the metropole itself. The lyricism of Henry Thoreau and William Wordsworth and the intensity of John Ruskin and the Quakers provided a foundation upon which the idea of cohabitation with nature was built with resolute confidence. The newly-independent nation-states of South Asia had

the option of carrying forward this legacy. The nationalist movement itself was energised by these sentiments. Instead, they chose a path that disavowed the lessons of the Mahatma and printed his face on each and every currency note as a tokenism that ironically captures the empty spirit of finance capital at its best.

The scholarship on environmentalism, as observed by Guha, seldom pays attention to these details. One of the reasons is that we still are looking for an escape from the impending crisis that will not impinge our lifestyle and unsettle the structures of hierarchy. What Speaking with Nature makes very clear is that there is no shortcut to redemption. Social media posts of walking on a march for clean water may stoke our egos for a while but it will hardly solve the energy crisis to which the increasing use of the internet is a massive contributor. What we need today is a multitude of conscientious objectors who will say no to every choice of excess and look at the world with more empathy and care. Ramachandra Guha, with his life’s work and his latest book, proves to be one such objector himself.