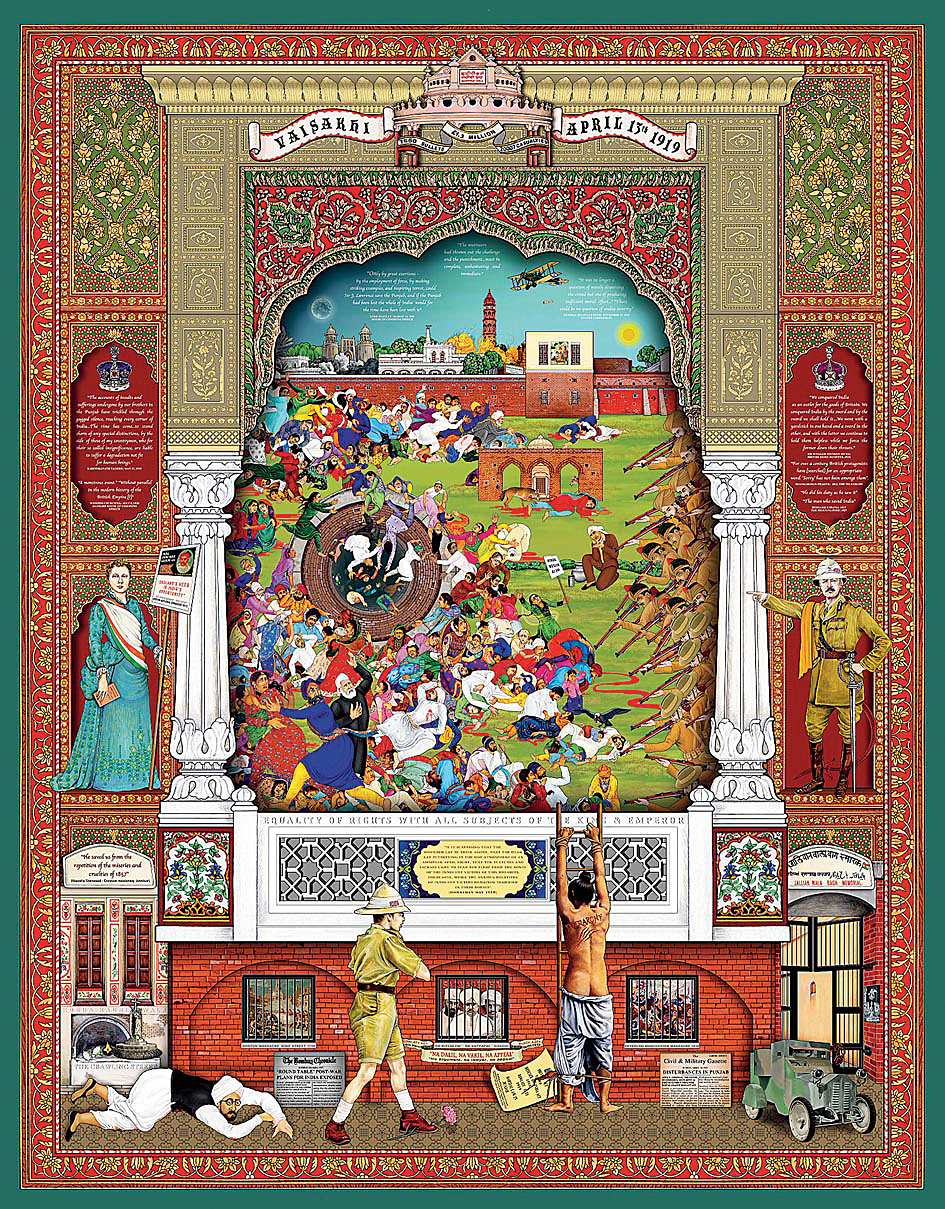

To historians of the 18th century William Dalrymple makes clear that his new book, The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire, steps into well-trodden territory. He understands the implications of his intervention, yet he confidently wades into a contentious debate and takes an interestingly nuanced position. In the debate as to whether the era of the later Mughals in the 18th century ushered in an undisputed ‘Dark Age’ or was unwittingly lit up by stories of ‘regional resurgence’, Dalrymple believes that notwithstanding the weight of new scholarship behind the thesis of the ‘creative or luminous 18th century’, the period was evidently one of relentless ‘anarchy’. In fact, he draws upon the words of the 18th-century poet of Delhi, Fakir Khair ud-Din Illahabadi, to give the title to his book. The ‘anarchy’, Dalrymple tells us, was wrought upon Mughal India by the East India Company as both corporate plunderer and founder of the British Empire.

Yet this is where a bit of the problem lies. So what is new about the East India Company’s life and misdeeds in India that Dalrymple wants to tell us? Several scholars have already written about the political, economic and military history of the Company in deeply researched academic monographs and journal papers. There is much in the popular domain too. Two widely read popular histories of the Company, for instance, came out in 2006 and 2012 respectively: the first by Nick Robins and the second by Tirthankar Roy. Both books offered an insider’s view of the Company beginning with its founding in 1600 by Royal Charter, its early life as a trader in Asian spices and then its awe-inspiring role in the establishment and running of a British Empire. Nick Robins writes a warts-and-all account of the Company’s history, its scheming directors, rapacious merchants, greedy shareholders, wars, famines, debts, rivalries and duels in meticulous detail and elegant prose. In the history of the East India Company, he argues, one could see the figurations of the modern multinational and the unceasing drives of corporate greed. Tirthankar Roy tells us a similar story, but focuses more on the role of Indian trading agencies in the fortunes of the East India Company, the clash between two cultures of business, conflicts over notions of contract and ‘trust’, and the eventual establishment of the trade monopolies of the company by stealth, treachery or firepower.

Dalrymple acknowledges both, but tells us he is not interested in offering a complete history of the East India Company, still less an economic analysis of its business operations. Instead, he seeks to understand how a single business operation based in one London office complex managed to replace the mighty Mughal Empire as masters of the vast subcontinent between the years 1756 and 1803.

His book takes us through tortuous stratagems and wars whereby the Company defeated its principal rivals — the Nawabs of Bengal and Awadh, the Mysore Sultanate and the great Maratha Confederacy and the Mughal emperor, Shah Alam, a man whose fate, Dalrymple writes, “was to witness the entire story of the Company’s fifty-year-long assault on India and its rise from a humble trading company to a fully fledged imperial power. Indeed, the life of Shah Alam forms a spine of the narrative that follows”.

For this reader, it is this structuring principle of the book that gives it its unique appeal and renders it so different from what has been written before. For what emerges from the richly researched historical narrative of Shah Alam’s life and that of the corporate archives of the East India Company is something akin to a modern ‘morality’ play. Although not in strict conformity with the medieval English literary form, Dalrymple’s book plays up the conflict between virtue and vice through a skilful juxtaposition of the rapacious soul of the East India Company with the calm fortitude of a defeated but still proud Mughal emperor.

The clue to understanding the deliberate moral positioning of Dalrymple’s cast of characters lies in the section just before the Introduction. Titled “Dramatis Personae”, this section gives us short blurbs on Dalrymple’s ‘characters’ drawn from the East India Company, the Mughals, the Nawabs, the Sultans of Mysore, the Rohillas and the Marathas. Dalrymple’s descriptions of the individual predicaments of this group positions Robert Clive at one end of the moral spectrum and Shah Alam at the other. Clive’s ambition and avarice are played up against Shah Alam’s grace and fortitude. In Dalrymple’s words, Shah Alam’s reign was hardly glorious, “but his was nonetheless a life marked by kindness, decency, integrity and learning, when all such qualities were in short supply’’. Shah Alam failed to protect the empire of his Timurid ancestors and caved in before a band of audacious traders, but in the end he left behind a compelling legacy. Fifty years on, his grandson would become the centre of the first and fiercest assault on the Company.

Dalrymple’s elegiac evocations of the tragic vicissitudes of Shah Alam’s life temper his hard-nosed narrative of the East India Company’s depredations. The Anarchy remains a unique meditation on corporate avarice told with the deftness of a scholar and the charm of a raconteur. But the story of pillage, no matter how riveting, remains a tad less compelling in the face of the story of the quiet and indomitable spirit of a less celebrated Mughal emperor.

The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire by William Dalrymple, Bloomsbury, Rs 699