Interest in Subhas Chandra Bose’s life continues unabated. Even today claims and counter-claims regarding his death in a fatal plane crash in Taiwan rage on. In the recent past, a lot of attention had been directed to historical research seeking to trace the chronology of Bose’s later life, especially his stays in Germany, Italy, Singapore, Japan and Burma. Such works have often led to diverse inferences, continual speculations, occasional wild allegations and intermittent demands for declassification of files and documents pertaining to Bose’s life. The past decade in particular has witnessed a plethora of critical explorations of various aspects of Bose’s life as researchers have ceaselessly tried to stitch together the sequence of events following his miraculous escape to Germany. Notable among these recent efforts include Sugata Bose’s His Majesty’s Opponent: Subhas Chandra Bose and India’s Struggle against Empire, Kingshuk Nag’s Netaji: Living Dangerously, Ashis Ray’s Laid to Rest: The Controversy over Subhas Chandra Bose’s Death, Shreyas Bhave’s Prisoner of Yakutsk: The Subhash Chandra Bose Mystery Final Chapter, Vera Hildebrand’s Women at War: Subhas Chandra Bose and the Rani of Jhansi Regiment, Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s Nehru & Bose: Parallel Lives, Marshall J. Getz’s Subhas Chandra Bose: A Biography, Krishna Bose’s Emilie and Subhas: A True Love Story, Leonard A. Gordon’s Brothers Against the Raj: A Biography of Indian Nationalists Sarat and Subhas Chandra Bose as also several other works. Bose’s eventful life continues to fascinate historians, researchers, politicians, bureaucrats and readers alike.

The historical fiction, Mahanayak: Subhas Chandra Bose — A Novel, by the Sahitya Akademi Award winner, Vishwas Patil, is no exception to this cult. In fact, Keerti Ramachandra’s brilliant translation (from the original work in Marathi) not only makes for an absorbing evaluation but also provides access to a wider cross-section of readers across the world. What sets Patil’s work apart is his sensible and extremely intelligent attempt at writing well-researched fiction, and not another research-based biography of Bose. Historians and scholars compiling his biographical details invariably hit the stumbling block of the sheer lack of evidence. Such lacunae, however, fail to dampen Patil’s narrative — as the veil of fiction allows him to consider aspects of Bose’s life which perhaps an assiduous biographer would have desisted from exploring.

Patil traverses crucial political spaces in Bose’s life based on meticulous research across various countries, often braving diverse, unenviable obstacles. His imaginative reconstructions not only fill spaces in the curious readers’ minds but also lead to a riveting reading experience as readers gain a unique insight into interactions between notable political personalities — largely based on a rare amalgamation of historical research and ingenious imagination. In fact, such an interesting interface between the mind’s eye and historical scrutiny takes the reader on an enthralling journey through the most turbulent period of India’s freedom struggle.

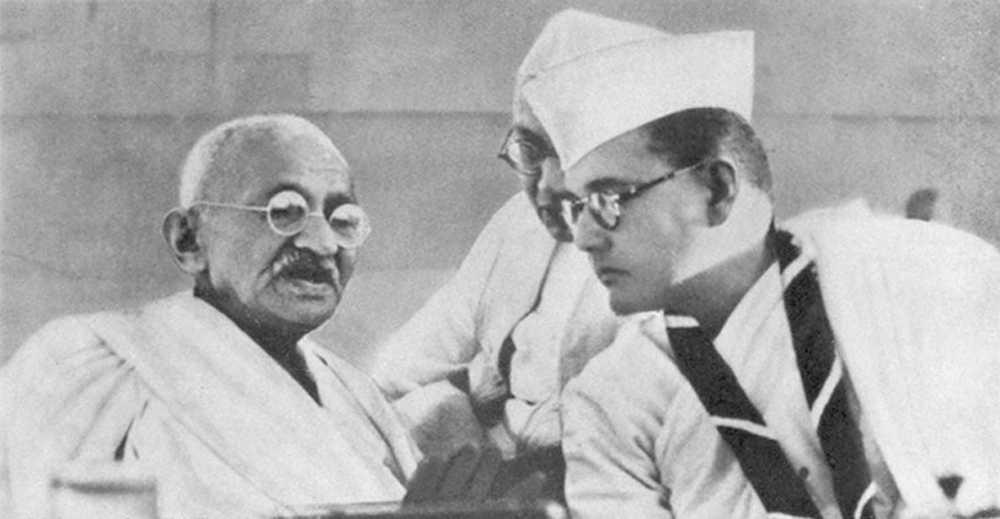

Patil initiates his narrative focusing on the steadfast loyalty that Bose’s personality inspired through a brief account of the die-hard commitment of the imprisoned Azad Hind fighters: Shah Nawaz Khan, Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon and Prem Sehgal. Their indomitable resilience against the British authorities opens the door for an inspiring biographical expedition — a journey which gathers momentum with the mushrooming of ideological differences between Bose and contemporary political giants like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and others. In this context, mention must be made of Gandhi’s reactions to the convincing defeat his candidate, Pattabhi Sitaramayya, suffered in the historic Tripuri Congress against Bose.

Gandhi made his feelings known the very next day through a statement. “Subhas Chandra Bose has won a decisive victory over Dr Pattabhi Sitaramayya. I was opposed to his re-election from the beginning. Also, I was solely responsible for not letting Pattabhi withdraw his nomination. That is why I take it as my personal defeat and not Pattabhi’s.”

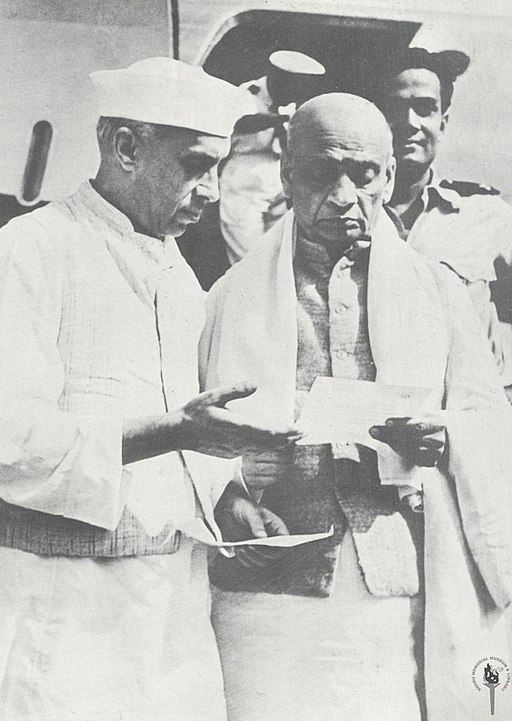

Running parallel to such depictions of political upheavals, frictions and clashes of personality is an adequate insight into Bose’s personal life: the reassuring presence of mejda or Sarat Chandra Bose and his wife, Bibhabati, his deep attachment to his parents, Janakinath Bose and Prabhabati Bose, and the ever accommodating love and assistance of Emilie Schenkl. Patil’s recreation of Bose’s thrilling escape from his Elgin Road residence conjures up a rare visual spectacle of trepidation and expectation. His short, perilous stay in Kabul, his incredible journey to Berlin (incognito: disguised as Orlando Mazzotta), his subsequent reunion with Emilie have been convincingly delineated.

Bose’s rendezvous with Hitler (May 29, 1942) marks the culmination of Patil’s fictional narrative. Bose’s gift for Hitler, a copper-coloured statue of Buddha, paves the way for an interesting yet extremely amusing conversation. However, in spite of such indulgences, Patil resists the temptation of making ineffectual speculations. He ends his novel with a vivid description of Bose’s demise at the Nanmon Military Hospital, where he succumbs to his injuries suffered in the fatal plane accident. The narrator justifiably shifts his focus to an exploration of the ambience of overwhelming loss and bereavement, transcending geographical barriers: “Who were all these people — nurses, ward boys, army staff? What nationality? What race? Grief had dissolved all boundaries. The Taipei Military Hospital was deluged in tears.” Patil’s fictional account of Bose’s life should be an absorbing read for all, irrespective of an individual’s political allegiance or ideological stand in turbulent times.

Mahanayak: Subhas Chandra Bose — A Novel by Vishwas Patil, Eka, Rs 799