Generally described as the sangh parivar, the RSS was set up in 1925 by Keshav Baliram Hedgewar, a Telugu Brahmin doctor from Nagpur. Its objective has been to establish a Hindu rashtra. According to the RSS, the most damaging threat to India since 1947 has been the effort of the Congress leadership to impose Western enlightenment that perceives tradition as an impediment to progress.

The authors claim that they have applied a case-study approach in the preparation of the contents of this book, which is different from the historical approach they employed in their first book. In the current approach, they have selected nine issues and raised four key questions in analysing these issues. First, why has the RSS increasingly relied on its affiliates to convey its message? Second, how does the RSS manage its links with affiliates, especially its political affiliates? Third, in spite of policy differences among its affiliates, how does the affiliation stay together? Fourth, how has the growing social inclusiveness of the sangh parivar shaped its perception of democracy, secularism and Hindutva?

Among the chapters, chapters 6 and 7 analyse the RSS approach to Muslims as a people and Islam as a religion. The book examines the RSS inspired quasi-affiliate, the Muslim Rashtriya Manch. Its purpose is to generate support for Hindu nationalism among Muslims. In the chapter on this, the authors conclude that the RSS does not resist the MRM’s initiatives to close the gap between Muslims and its version of patriotism, but is willing to accommodate Muslims only on its own terms. These terms, however, remain unclear. In a three-day conclave held in Delhi in September, the RSS chief, Mohan Bhagwat, spelt out his thoughts on Muslims and said that there is no Hindutva without Muslims and there is a place for Muslims in Hindutva. Meant for global attention, the conclave invited diplomats of 60 countries. But the question is: what is precisely the place of Muslims in Hindutva? Should Muslims be treated like Dalits and suffer indignity and humiliation or live as equals? Should the RSS ever make a statement saying that an able Muslim can also be the prime minister of India some day? Given that the RSS wants Muslims to live on its terms, such an ambition for Muslims is going to be denied.

Exclusive chapters on cow protection, the ghar wapsi movement, and the Ram temple issue enrich the content. On the issue of ghar wapsi, they conclude that the RSS walks a fine line. The authors cite that Rajeshwar Singh, an RSS pracharak in charge of the ghar wapsi movement to convert Muslims and Christians to Hinduism in western Uttar Pradesh, was removed from his position. He was told to go on sick leave indefinitely. Singh’s position on ‘love jihad’ created controversy for the BJP, which is why the RSS that believes in ghar wapsi is yet cautious about its commitment of patronage to people or organizations who are active with this agenda.

The RSS dictates many of the current government’s agenda, unprecedented in Indian history. However, the first such intervention began during the Morarji Desai government, which provoked Jayaprakash Narayan to write a stinging letter to Desai warning against the RSS’s influence.

The authors have extensive access to key functionaries, which is what makes this inside story authentic and credible. This is a very important contribution in the study of an organization whose influence is likely to increase in the future. For those who wish to fight for a secular India, it is crucial to know the mind of the RSS, and this book is a reliable source.

The RSS: A view to the inside By Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle, Viking, Rs 699

There are yet to be persuasive explanations for the dramatic rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party or the Hindu Right in India’s electoral politics in scholarly writings. What is, however, argued with greater clarity is the role and contribution of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh in the BJP’s expansion. Some view the RSS as constituting the real ideological DNA of the Hindu Right. For authors Walter K. Andersen and Shridhar D. Damle, The RSS: A view to the inside is the second attempt to share their analysis of the RSS by using their extensive access to RSS leaders and also key politicians with RSS pasts, like Narendra Modi, Ram Madhav and so on. The fact that two prime ministers, Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Narendra Modi, were groomed by the RSS is a good enough reason to study the organization. Their first book, The Brotherhood in Saffron, was published in 1987.

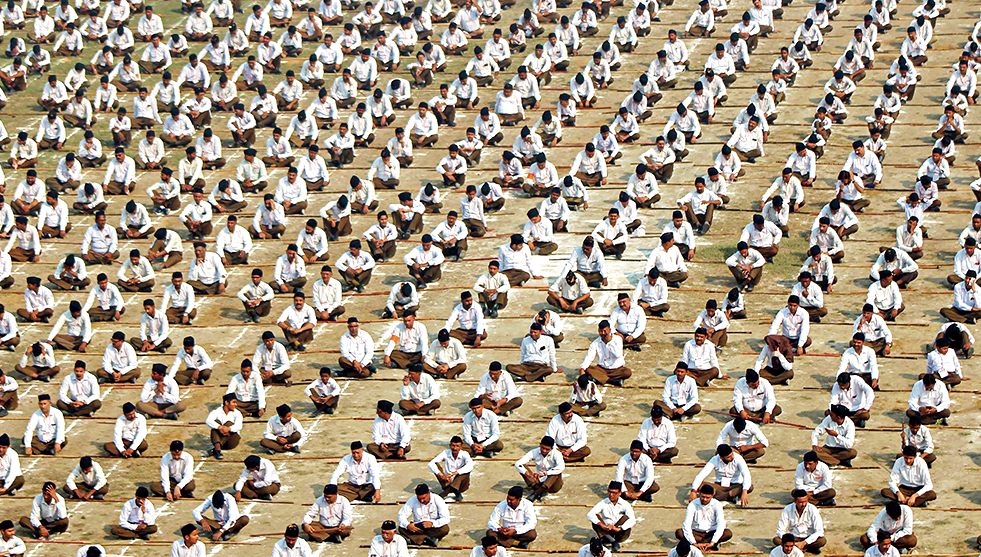

The RSS is the world’s largest non-governmental association, it claims. Close to 1.5-2 million take part in 57,000 daily shakhas, 14,000 weekly shakhas, and 7,000 monthly shakhas in 36,293 different locations, according to a report in 2016. On top of that, the RSS has six million alumni and affiliate volunteers. Without doubt, this is a formidable organization, but its rise has been dramatic in recent years.