The Push for Hindi

The arrival of Modi on the national scene has seen his government pushing Hindi with more enthusiasm than judgement. I got caught up in the undertow of the new zeal for Hindi when in reply to a question on Twitter, in all innocence, I asserted that Hindi was not our natural language. I was accused of being anti-national, of being a slave to a foreign language—as if the British had excreted their language on us as pigeons might spatter us with their droppings. Unfortunately for them, I was right: the Constitution of India provides for no ‘national language’. But being wrong rarely bothers a troll.

The ugly exchanges did, however, reveal two more essential truths about our country. The first is that, whatever the Hindi chauvinists might say, we don’t have one ‘national language’ in India, but several. The second is that the Hindi zealots, including their recent Southern converts like Venkaiah Naidu, whose assertion ‘Hindi hamari rashtrabhasha hai’ had provoked the recent debate, have an unfortunate tendency to provoke a battle they will lose—at a time when they were quietly winning the war.

Hindi is officially the mother tongue of some 41 per cent of our population; the percentage has been growing, thanks to the spectacular failure of population control in much of north India. It is also spoken by several who claim primary allegiance to other languages, notably Punjabi, Marathi and Gujarati. It is not, however, the mother tongue of the rest of us.

When Hindi speakers emotionally decry the use of an alien language imposed on the country by British colonialists and demand that Hindi be used because it speaks for ‘the soul of India’, or when they declare that ‘Hindi is our mother, English is a stranger’, they are missing the point twice over.

First, because no Tamil or Bengali will accept that Hindi is the language of his soul or has anything to do with his mother—it is as alien to him as English is. And second, because injecting anti-English xenophobia into the argument is utterly irrelevant to the issue at stake for those who object to the idea of a national language.

That issue is quite simple: all Indians need to deal with the government. We need government services, government information and government support; we need to understand easily what our government is saying to us or demanding of us. When the government does so in our mother tongue, it is easier for us. But when it does so in someone else’s mother tongue with which we are less familiar than our neighbour, our incomprehension is intensified by resentment. Why should Shukla be spoken to by the Government of India in the language that comes easiest to him, but not Subramaniam?

The de facto solution to this question has been a practical one—use Hindi where it is understood, but use English everywhere and especially in the central government, since it places all Indians from all parts of our country at an equal disadvantage or advantage. English does not express Subramaniam’s soul any more than it does Shukla’s, but it serves a functional purpose for both, and what’s more, it helps Subramaniam to understand the same thing as Shukla.

Ideally, of course, every central government document, tax form or tweet should be in every one of India’s languages. Since that is not possible in practice—because we would have to do everything in twenty-three versions—we have chosen to have two official languages, English and Hindi. State governments complement these by producing official material in the language of their states. That leaves everyone more or less happy.

Since the BJP came to power, however, they have not been content to let sleeping dogmas lie. The move to push Hindi has required governmental file notations to be written in that language, even where that undermines comprehension, accuracy and therefore efficiency.

Obliging a south Indian civil servant to digest a complex argument by a UPite subordinate writing in his mother tongue is unfair to both. Both may write atrocious English, for that matter, but it’s the language in which they are equal, and it serves to get the work done.

Language is a vehicle, not a destination. In government, it is a means, not an end. The Hindi-wallahs fail to appreciate that, since promoting Hindi, for them, is an end in itself.

This is what sustains the government’s futile efforts to make Hindi a seventh official language of the United Nations. PM Modi’s Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj dramatically declared that her government was willing to spend hundreds of crores of rupees to achieve this objective. Now in the United Nations, there are six official languages (used for formal speeches and translations of documents) and two working languages (in which the organization’s work is conducted daily). Similarly, in India, we have no single ‘national language’: Article 343 of the Constitution makes it very clear that Hindi is an official language. The Official Languages Act of 1963 says that Hindi and English are both official languages of India and the Gujarat High Court ruled in 2010 that Hindi is not the national language of India. So for India to be spending significant government resources in seeking to promote Hindi as a UN language has more to do with misplaced Hindi chauvinism than with constitutional principle.

It also has little to do with practical efficiency. Six languages have been made official languages at the United Nations because a number of countries speak them. Arabic does not have more speakers than Hindi, but Arabic is spoken as an official language by twenty-two countries, whereas Hindi is only used as an official language by one country, India. When I questioned her in Parliament, Ms Swaraj claimed disingenuously that Hindi is spoken in Mauritius, Fiji, Surinam, Trinidad and Tobago, and Ghana. But she failed to acknowledge that it is not the official language of any of these countries, and therefore not a means of official communication with any of them.

Indian diplomats using Hindi at the UN would, in other words, be speaking to themselves and to the Hindi-speaking portion of their domestic audience. This narrow, essentially political objective, does not justify expending vast sums of taxpayers’ money. If India were to have a prime minister or a foreign minister who prefers to speak Hindi (as we do currently), they can do so and we can pay for that speech to be translated at the UN. But that is not the same time as making it an official language. Why should we put our future foreign ministers and prime ministers who may be from Tamil Nadu or West Bengal in a position where they are condemned to be speaking a language they are uncomfortable with, merely because we are paying for it?

The irony is, as I observed earlier, that the Hindi chauvinists should realize they were winning the war. The prevalence of Hindi is far greater across India today than it was half a century ago. The Parliament has become a bastion of Hindi; you hear the language now twice as often as you hear English, and three times as often as you did in the previous Parliament, when stalwarts like Pranab Mukherjee and P. Chidambaram refused to speak anything but English on the floor of the House. Our present prime minister speaks only in Hindi, and his ministerial colleagues, with only a handful of exceptions, try to emulate him.

But the inevitable triumph of Hindi is not because of Mr Modi’s oratory, or Mulayam Singh Yadav’s imprecations, or the assiduous efforts of the parliamentary committee on the promotion of Hindi. It is, quite simply, because of Bollywood, which has brought a demotic conversational Hindi into every Indian home. South Indians and Northeasterners alike are developing an ease and familiarity with Hindi because it is a language in which they are entertained. In time, this alone will make Hindi truly the national language.

But it would become so only because Indians freely and voluntarily adopt it, not because some Hindi chauvinist in Delhi thrusts his language down the throats of the unwilling.

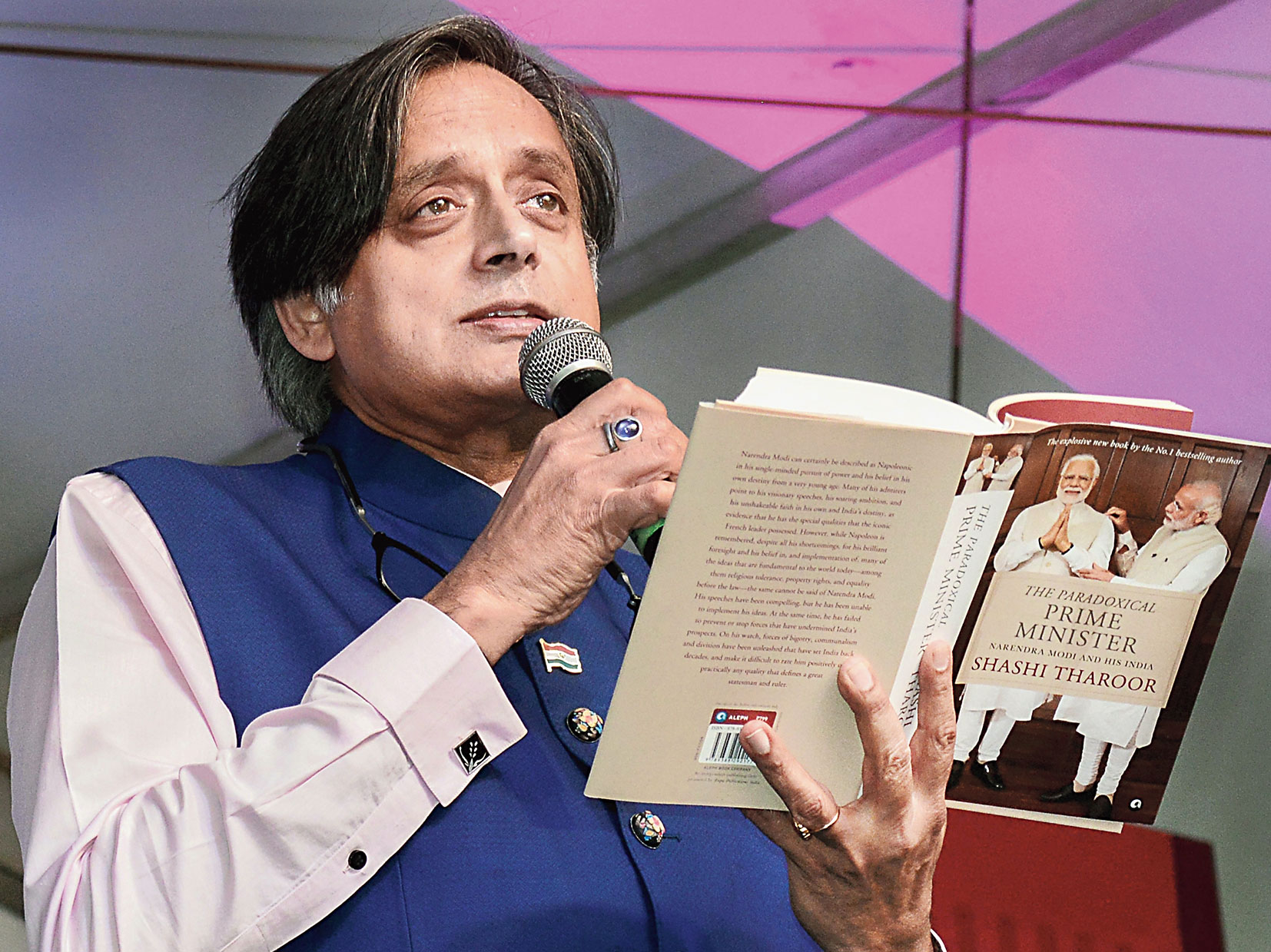

Extracted from The Paradoxical Prime Minister by Shashi Tharoor, with permission from Aleph Book Company

Congress Member of Parliament and writer Shashi Tharoor's latest book, The Paradoxical Prime Minister, on PM Narendra Modi, is getting the expected amount of attention - a lot. It has already stirred a controversy with his analogy - attributed to an RSS source - between Moditva and Hindutva and 'a scorpion on a Shivling' The book has more than scorpions, shivlings and floccinaucinihilipilification. In this excerpt, Tharoor takes on Hindi chauvinists.