Further, Uday Chandra analyses the complicated negotiations in the somewhat politically marginal Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. Also, the Aam Aadmi Party remains in contention as a welfare-oriented centrist plank in Delhi and Punjab, in spite of various blunders committed by its inexperienced leadership, as indicated in contributions by Nissim Mannathukkaren and Pritam Singh. The troublesome situation in Jammu and Kashmir, where communalism has reached new depths, is reported on by Aijaz Ashraf Wani.

However, it is in the cow belt that divisive politics has got a free hand. Zoya Hasan has argued that the Congress completely vacated the field, instead of offering a challenge on ideological grounds. Sudha Pai and Avinash Kumar further relate that the BJP was transformed in Uttar Pradesh into an election machine, whereas key Opposition parties meekly surrendered. The serious repercussions of the communal onslaught have been studied in chapters by Harsh Mander and Rudolf C. Heredia. Charu Gupta examines the aggressive deployment of ‘love jihad’ and ghar wapsi by non-State actors who now have access to power to promote their agenda. The shift to strong-arm Hindu nationalism can also be seen in foreign policy posturing, as highlighted by Arndt Michael. Amidst all these, Mujibur Rehman reminds readers that Muslims will remain staunchly committed to broad-based national-secular politics, in spite of occasionally succumbing to some lollipops.

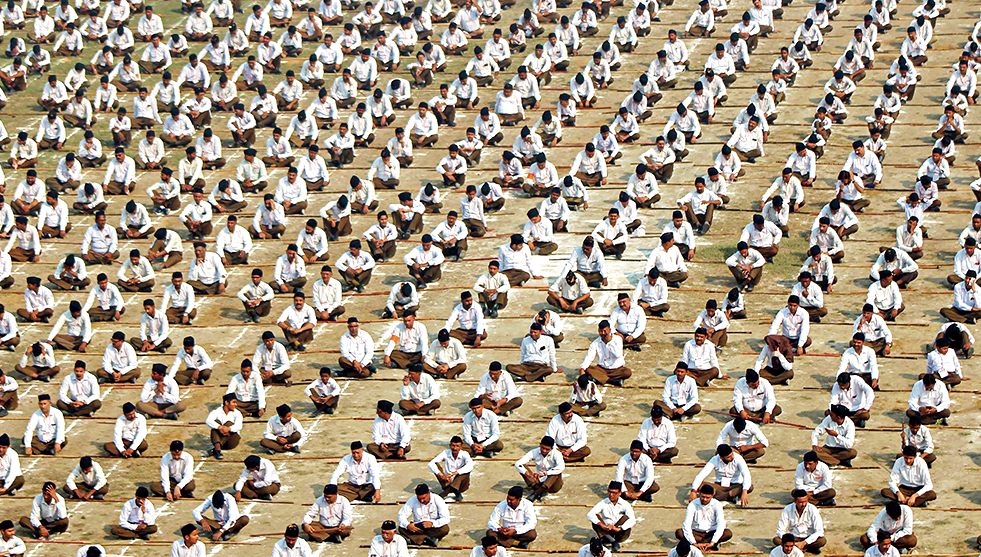

The 2014 electoral landslide deserves to be recognized as a majoritarian blitzkrieg on the country’s political landscape. Operating somewhat surreptitiously and exploiting massive anti-United Progressive Alliance sentiments, built on a crescendo of an India-against-corruption campaign, the BJP walked away with all the power and glory, although the AAP, led by Arvind Kejriwal, also benefited in Delhi. Seeking to change the character of the polity, the right-wing will now push for its long-standing dream of Hindu rashtra. The resultant setting aside of constitutional safeguards will cause severe ruptures in social and political relations across castes, regions and religions.

The Indian State has been able to manage the diversity with considerable success, but the deadly mix of violence and exclusion of minorities and Dalits can put an enormous strain on the political system. Even if the aggressive saffron ideology cannot be sustained through successive electoral victories, it will have considerably damaged the pluralistic fabric of society. A course correction, therefore, appears necessary. In Rehman’s opinion, the plausibility of a setback to the BJP’s juggernaut is higher in the destabilization of the current leadership through internal sabotage rather than from any challenge that Opposition parties could orchestrate.

Prominent Opposition leaders are often seen making smart moves, but they are eventually working at cross purposes. A credible countrywide Opposition is still a far cry, although the regions are continuously signalling that cooperative federalism is the way forward. Besides, on the national scale, the public is not yet entirely disgusted with the BJP to dump it if there is no united Opposition. Such has been the power of hatred generated by the Hindutva brigade that even the symbolic shutting out of Muslims is enough for the strong leader to remain secure in his position. Elections are also approaching; the Ram Mandir pitch must be raised again. In the make-believe world of popular politics, something great is going to happen to the nation soon. Of course, when control goes haywire, the last resort can sway a billion or more. The volume under review offers enough material and insights as an ominous portent.

As many as 16 fine scholars have come together to shape this voluminous collection of essays - Rise of Saffron Power: Reflections on Indian Politics - on the historic 2014 general elections, the aftermath of which continues to rattle a vast country of subcontinental scale. The traditional Gandhian principle of non-violence and modern Nehruvian style of inclusive governance, which served as the model to run the country during the past 71 years, are now being systematically abandoned.

The larger picture could be disturbing, but specific details from different regions reveal thought-provoking propositions. James Chiriyankandath illustrates how the southern Indian states almost wholly bucked the Narendra Modi wave where regional parties continue to thrive. Ritu Khosla further shows that the Telangana Rashtriya Samiti and the Telugu Desam Party ensured that the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Indian National Congress had little appeal in undivided Andhra Pradesh. Maidul Islam notes that Mamata Banerjee’s Trinamul Congress is fully entrenched as a dominant regional party in West Bengal, marginalizing the Congress, pushing Left parties into terminal decline and thwarting the BJP’s relentless inroads. Cornelia Guenauer has also pointed out that in Meghalaya, and in the Northeast generally, the political discourse hinges on feelings of alienation from the Indian State and concerns over the influx of outsiders. The BJP was able to achieve some success through strategic alliances with local outfits, but there was no wave as such.

Rise of Saffron Power: Reflections on Indian Politics, Edited by Mujibur Rehman, Routledge, Rs 1,250