The story could have been very different last week when the Swedish Academy named the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Literature for 2018 and 2019. It could have, as the Nobel committee head, Anders Olsson, loftily claimed, been a chance to go beyond the “more Eurocentric perspective on literature,” that the award has always taken, and instead “[look] all over the world.” Moreover, after postponing the 2018 award in the wake of a sexual harassment scandal, it was expected that the academy would honour writers who could be appreciated for their literature and their politics.

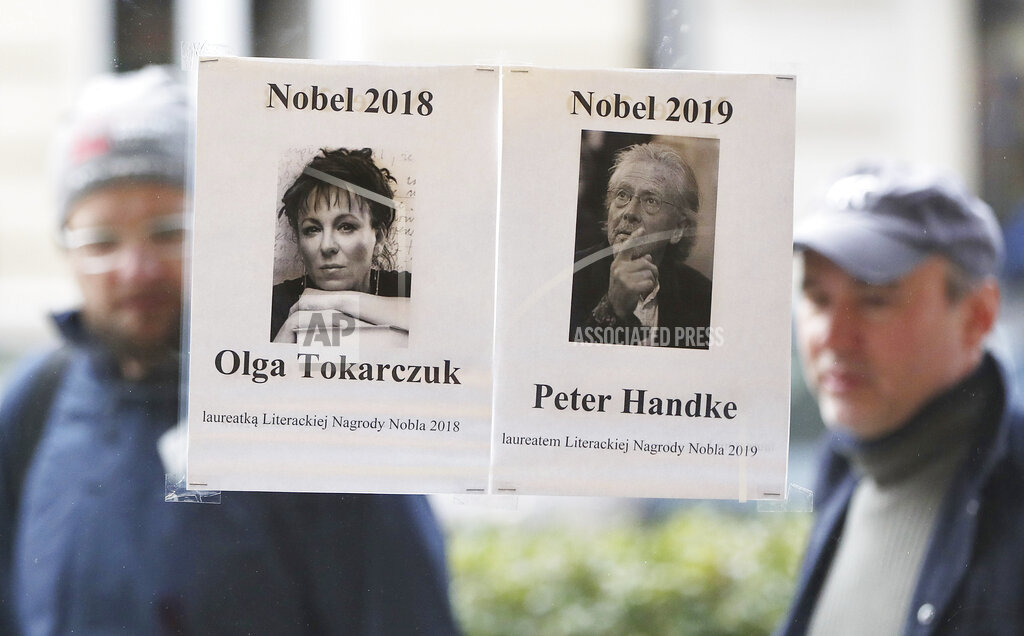

The story, of course, remained much the same, even after a year of purported introspection. The prize went to two European authors, one of whom is a well-known apologist of the Bosnian genocide. Olga Tokarczuk’s work, to be fair, could not be more different from Peter Handke’s: her writing rebels consistently against border nationalism, questions the jingoistic narrative of Polish history and explores literary bridge-building. This has earned her not only the wrath of the right wing in Poland, but also enough threats to her life for her publisher to get bodyguards for her. Her win is also, in a way, a triumph for women, given that she is only the 15th woman to get the prize since 1901.

Then there is Handke, who gave a speech at the funeral of the Serb dictator and war crimes accused, Slobodan Miloševic, and in whose play, Voyage by Dugout, a character speaking in defence of Serbs — and, by extension, the mass killings they carried out — says, “You know it was we who protected you from the Asian hordes for centuries. And without us you would still be eating with your fingers”. It is clear that the authors’ literary output is a study in contrasts.

This leads to the question that the academy seems to have answered: even if the intellectual rigour is undisputed, can all moral positions be equal and deserving of the same admiration? In picking both Tokarczuk and Handke, the academy has implied that there exists a moral equivalency between their positions. The part of Alfred Nobel’s will that pertains to the prizes says that “the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction” shall be awarded. Is the outcome of this year’s prize an exercise in that idealism, in any way?

There is no doubt that all literature awards are different. Unlike the Booker, which goes to the best English-language novel, the Nobel recognizes an author, and is therefore an observation on a whole body of work. It is also true that these awards do not clearly define the guidelines that authors must follow to win. However, without compromising on literary quality — this is entirely subjective anyway — is there not a case to be made for giving the ideas and values of the writing more prominence? And while authors are free to say whatever they please, should not ‘good literature’ evoke feelings and ideas that are not fuelled by hate and violence?