When I was about 8 years old I wrote my first fan letter, to Roald Dahl, for “Danny, the Champion of the World.” Not knowing where to find the author, I addressed the envelope to “Roald Dahl, England,” and added extra postage stamps.

I never heard back.

Years later, I learned that Dahl was an anti-Semite. “There’s a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity toward non-Jews,” he said in 1983, adding, “even a stinker like Hitler didn’t just pick on them for no reason.”

It’s a despicable view. But I would never purge Dahl’s books — arguably the finest children’s literature in English — from my shelves. People with wretched prejudices can still be great writers. People who restrict their literary tastes to authors whose moral and political convictions they approve of are nearly guaranteed to have no taste at all.

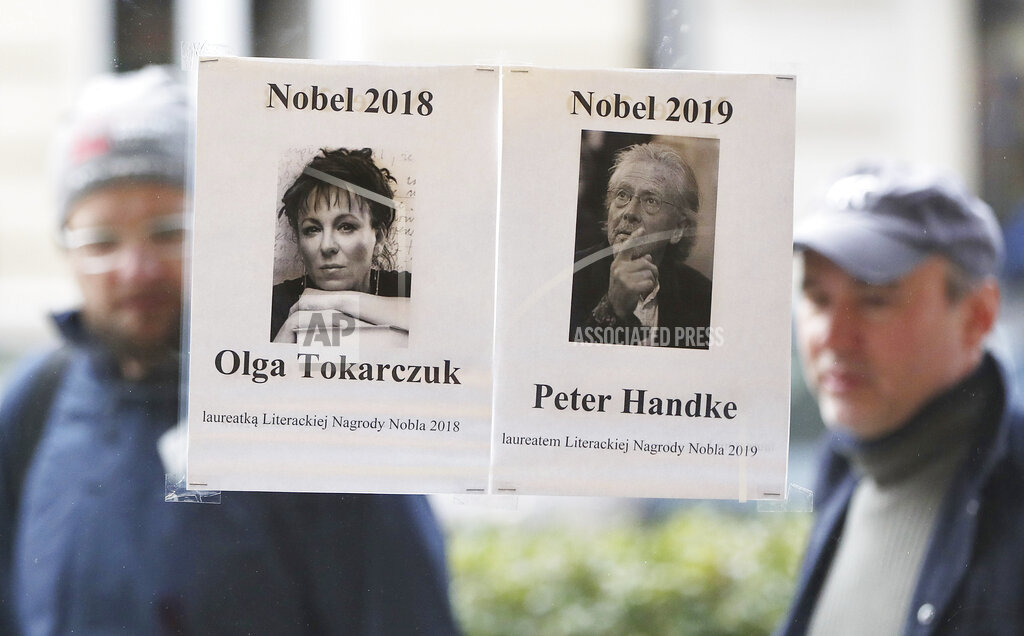

That’s something to consider following the furor that’s greeted this year’s Nobel Prize in literature, awarded last week to the Austrian novelist and playwright Peter Handke. Wolfgang Ischinger, a former German ambassador to the U.S., called the choice “Shameful!” PEN America said it was “dumbfounded by the selection of a writer who has used his public voice to undercut historical truth and offer public succor to perpetrators of genocide.” In The New York Times, Bosnian-American novelist Aleksandar Hemon wrote that “Handke’s politics irreversibly invalidated his aesthetics.”

Handke’s politics are indeed shameful. He became politically notorious in the 1990s for defending Serbia’s conduct during the Balkan wars — a defense that included equivocations, nearly to the point of denial, regarding Serb war crimes. In 2006, he eulogized Slobodan Milosevic, the Serbian dictator principally responsible. Asked about the corpses of Muslims massacred in Srebrenica in 1995, Handke replied, “You can stick your corpses up your arse.”

Then again, if Handke’s opinions were a cause of outrage, it was, in part, because he specialized in outrage: One of his earliest works is a play called “Offending the Audience.” That and subsequent works (most famously, “The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick,” later made into a film by Wim Wenders) made him one of Europe’s most celebrated writers long before his Serbia obsession. Like other artists before him — Colette comes to mind — Handke turned scandal into fame and fame into scandal.

Handke also resembles other writers, Nobel laureates in particular, in his awful political judgment. The late British playwright Harold Pinter (Nobel, 2005) was only slightly less zealous than Handke in his defense of Milosevic. Günter Grass (1999) opposed Germany’s reunification and spent most of his life chiding his countrymen for their failure to confront their Nazi past, only to confess late in life that he had been a member of the Waffen SS. Portugal’s José Saramago (1998) was an unrepentant hard-line leftist who, as a newspaper editor, purged and abused journalists who did not tow the Communist Party line. Gabriel García Márquez (1982) was a close friend of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. Jean-Paul Sartre (1964) visited the Soviet Union in 1954 and praised it for its “complete freedom of criticism.”

Given these precedents, why has the reaction to Handke’s Nobel been so neuralgic?

Part of the answer, surely, is that Handke is considered a fascist (though his full political views are hardly clear), whereas Pinter, Grass and the others were all men of the left, whose fellow traveling with despots could glibly be excused, at least by other leftists, as an excess of idealism. After Saramago died in 2010, PEN America — an organization explicitly dedicated to protecting free expression — paid him fulsome tribute, with no mention of his censorious past.

But part of the answer, too, is that we live in an age that is losing the capacity to distinguish art from ideology and artists from politics. “I’m standing at my garden gate and there are 50 journalists,” Handke complained on Tuesday, “and all of them just ask me questions like you do, and from not a single person who comes to me I hear they have read any of my works or know what I have written.” He has a point. He didn’t win a Nobel Peace Prize or some other humanitarian award. His art deserves to be judged, or condemned, on its artistic merits alone.

What’s the alternative? Those who think that a core task of art is political instruction or moral uplift will wind up with some version of socialist realism or religious dogma. And those who think that the worth of art must be judged according to the moral and political commitments of its creator ultimately consign all art to the dustbin, since even the most avant-garde artists are creatures of their time.

For myself, I plan to add one or two of Handke’s books to my shelf, at least the nonpolitical ones. They’ll sit alongside Pinter, Saramago, Grass and, of course, Dahl — writers to whom I will always feel grateful, not least because they did not choose politics as their vocation.