It’s a self-hating exercise when a critic loves a novel despite her inability to untangle why she loves it so. Love, after all, can be critical — and, perhaps, should be — when we love someone through the form of criticism.

In Anton Chekhov’s short story Love, a man recounts his relationship with his wife, Sasha, from infatuation to marriage. At the beginning, he’s desperately in love, unable to see past the honeymoon phase of their relationship. By the time they’re married, he can’t help but see how dull she is, how far she is from the woman he had idealised. He admits that Sasha embodies all the things that put him off: scatter-brained, unintellectual, even a little vacuous, and then adds: “I forgive it all almost unconsciously, with no effort of will, as though Sasha’s mistakes were my mistakes… The explanation of this forgiveness of everything lies in my love for Sasha, but what is the explanation of the love itself, I really don’t know.” In love, this is precisely where the narrator succeeds, but in criticism, this point of unrecognition is exactly where the critic falters, even fails.

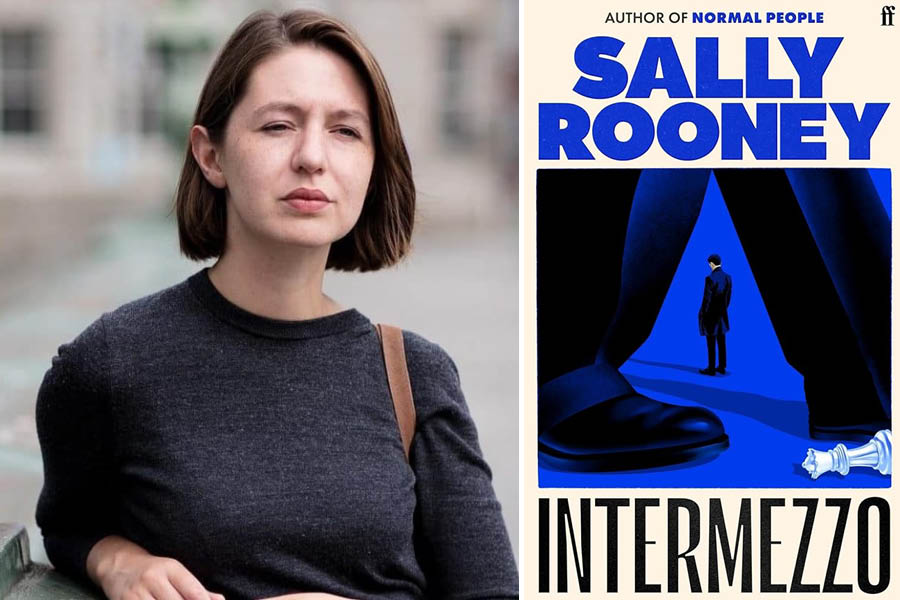

‘Intermezzo’, Rooney’s longest book ever, makes a clearer attempt at growing up than any of her past novels

Sally Rooney’s latest novel, Intermezzo (Penguin Random House in India), is out today. The Rooney reader now shares the same reputation as the listener of Taylor Swift or the reader of Sylvia Plath — privileged women who can’t see past themselves and the platitudinous problems in their own bite-sized worlds. The Rooney reader, and sometimes the Rooney reviewer, can’t help but see Rooney in her characters. And what do you do when you see yourself in something? You defend it.

Intermezzo, Rooney’s longest book ever, makes a clearer attempt at growing up than any of her past novels. For one, her characters face an undeniably terrible event — the novel follows the aftermath of a father’s death on his two sons, Peter and Ivan. Peter, a lawyer, finds himself caught between wanting to rekindle a relationship with his ex-girlfriend, Sylvia, who no longer wants him after a traumatic accident, and navigating a casual but intense connection with 20-year-old Naomi. Meanwhile, Peter’s younger brother, Ivan, a brilliant but socially awkward chess prodigy, falls in love with Margaret, a woman 10 years his senior. As Peter and Ivan grapple with their individual romantic entanglements, their fraternal relationship remains fraught, filled with long-standing resentment and a fundamental inability to understand one another.

In Intermezzo, Rooney is explicitly intertextual, incorporating many quotations from other texts, almost all canonical. Unless you’re an expert, you wouldn’t even notice that she is quoting them, considering the finesse with which she weaves them into her own narrative. In this excerpt from Peter’s perspective, there is a reference to Edna St. Vincent Millay’s 1920 poem What Lips My Lips Have Kissed, and Where, and Why:

She lies face down with her head in her arms. Familiar choreography, rehearsed together and with others, both. What lips my lips have. There is no one else, he could say. Someone, but not. I’m sorry. I love you. Her. Both. Don’t worry. Don’t say it. Christ no. Christ commands us universally to love one another.

‘Intermezzo’ is a first in Rooney’s oeuvre, where the female perspective is entirely abandoned

As in her previous novels, each of Rooney’s characters in ‘Intermezzo’ hesitantly fits into a trope Getty Images

Does Rooney want to move beyond commercial fiction? It’s unclear, but Intermezzo invites that reading. Some critics already praise her concise, exacting prose. They might even cite lines like “He turned her over on her back, gently, easily, and lying down on top of her he smoothed her hair from her face, and they kissed again” as proof of a style beyond genre conventions. Yet, this sentence, and much of Rooney’s writing, still shares stylistic elements commonly found in commercial fiction.

I can’t tell if Intermezzo was exhausting to read because Rooney’s writing was shedding its adolescence. But the more I read the novel, the more languorous it became, much like her earlier works. There’s something so simple about the way Rooney writes that it all ends up in perfect symmetry, like a little puzzle box that readers have to put together and eventually be pleased with the picture. But it’s so effortless precisely because there is a picture on a puzzle box you can use as a reference. Like in all her other novels, each of Rooney’s characters hesitantly fits into a trope. Peter is the older man gone rogue after a bad break-up, Ivan the wunderkind who struggles with his fallibility, Sylvia the woman who doesn’t want to let go, Margaret the older woman who hates herself for wanting what’s not conventional, and Naomi the run-of-the-mill manic-pixie-dream-girl the reader is forced to encounter through the male narrator’s eyes.

This novel is written in the third-person limited perspective, alternating between the viewpoints of Peter and Ivan. This is a first in Rooney’s oeuvre, where the female perspective is entirely abandoned — the only exception being a short interlude where Margaret takes over for a smidge. (It is also her first book where none of the characters are writers.) Intermezzo is almost difficult to read from Peter’s perspective, where the narrative drives the reader through a brain fog. Receding into the almost logical but disarmingly plaintive perspective of Ivan afterwards seemed just as lonely and sad as other Rooney characters we’ve previously known, like Marianne from Normal People, Alice from Beautiful World, Where Are You and, most notably, Frances from Conversations with Friends.

Everything typical of Rooney predictably finds its place in Intermezzo. Her characters continue to grow with her and the times, with Gen Z now officially part of her authorial stamp. Some of the female characters still seek degradation in bed, and communication remains elusive, as characters consistently fail to address what’s truly bothering them. The familiar distance Rooney creates between a character and their desires, as well as between the characters themselves, never quite closes in. In fact, Intermezzo might be the first novel where Rooney’s characters themselves acknowledge this inability to talk to one another. When Peter and Ivan finally confront each other after a period of silence — caused by Ivan blocking Peter — the latter demands, “When I was the one who needed help, where were the two of you?”, referring to Ivan and their father. He follows with, “No, you didn’t want to talk, you didn’t want to know.” Ivan responds by shoving Peter, who slaps him in return, knocking him to the ground as Ivan cries out in pain.

Rooney forces one to distinguish between the selves of the critic and the reader

Why is Intermezzo not Rooney’s best? It relies too heavily on everything that makes Rooney her, failing to push her already familiar characters in new directions. It’s too simple and too predictable, all while pretending to be otherwise. Most of all, it’s the projection of Rooney from her last three novels — as if an algorithm had predicted this is where her fourth novel should go.

Intermezzo forces us to confront whether, as critics, we should love Rooney’s novels, even if we do so as readers. I don’t have to look far to run into critics who will argue that even when Rooney’s subjects are frivolous, elements like repetitive plotlines or seemingly vapid characters are actually intentional choices, reflecting broader thematic concerns about relationships, identity and modern life. This penchant of contemporary criticism raises a larger question: is there a tendency to over-intellectualise flawed works simply because we enjoy them? Can a novel’s perceived weaknesses, such as repetitiveness or superficiality, be redeemed by simply claiming artistic intentionality? If we can find meaning in a work, does that mean its execution is no longer open to criticism?

Inadvertently or otherwise, Rooney forces the reader to distinguish between the selves of the critic and the reader. I admit that she’s more complicated than a ‘guilty pleasure’, but to say that a novel is good because it depicts what’s bad about the form of the novel, the commercialisation of the said form and what it has done to readers — instead of for them — is to say nothing at all. Like most people who love Rooney, I want to assert that the book itself makes no claims about what it is. The book is perhaps not all bad, but the way it has been read is. Don’t fool yourself into criticality when even your subject herself is opposed to a pedestalised reading: “I don’t need to be over the reader’s shoulder, saying, ‘What do you think of that page?’” Rooney said in a recent interview with the New York Times.

When will we tire of this charade, excusing a novel’s flaws with witty book summaries? Can’t we love a book and still acknowledge that it’s probably a bad one? Will we always be bad readers? Rooney doesn’t care for these affectations. Perhaps that’s why she gets away with being the better writer.

Diya Isha is an editor at a Delhi-based publishing consultancy. You can find her on Instagram @contendish