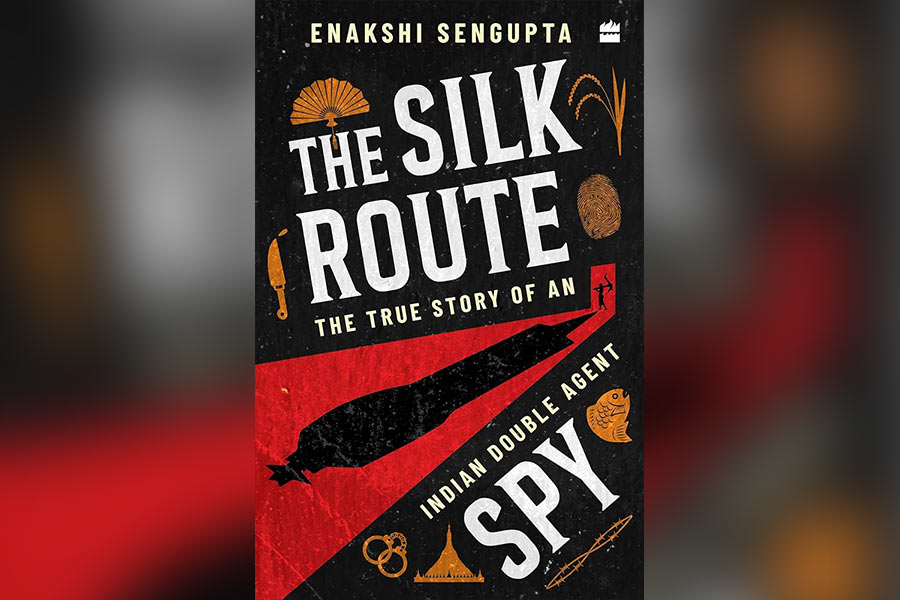

A question I asked myself while reading Enakshi Sengupta’s The Silk Route Spy: The True Story of an Indian Double Agent (HarperCollins) is what makes someone worthy of literary posterity, of being immortalised by a biographer. ‘Worthy’ suggests a stringent morality, but is it that simple? Think of Sherlock Holmes, and the act of posterity that John Watson undertakes as he narrates his subject’s cases to us. Holmes is hardly a perfect character. He’s as jagged as they come — blunt, perhaps too forceful, not to mention his rankling arrogance. But it’s perhaps this jaggedness that draws us to him, that makes him larger than life — the simple capacity to be imperfect.

Sengupta’s The Silk Route Spy does not seem to acknowledge this reality of characters. The story of Nandlal Kapur, a double-agent working for the British empire while colluding with the revolutionaries of the Freedom movement, is a story that could write itself. With such an intriguing premise opens a question that parries the subject it attempts to unspool: “Was Nandlal Kapur a traitor or a patriot?”

Telling, not showing, is Sengupta’s preferred option

The Silk Route Spy opens in 1920s Punjab, where Kapur, the eldest of his family, is recruited by the British. As he trains for the job, he lives in his family house, going to work while hiding who really employs him. His personal conflict arc begins the first time a piece of information he relays leads to the arrest of a group of revolutionaries building grenades. Nandu, as the character is anointed, turns from a boy who wants to see the world to a man conflicted about realising his desires. While this foundation holds promise, the novel doesn’t show us how the character changes. Instead, it tells us, and we’re expected to believe:

The boys were brutally beaten and then dragged out. Nandu noticed their eyes, full of loathing and defiance. Those eyes haunted him for a long time. As they were forcefully put into the police van, they turned around to look at him with aversion and hatred. Perhaps they knew that he had been instrumental in getting them caught. Something stirred inside him. Was he doing the right thing? The thought refused to leave his mind as he pedalled his way to the cantonment and then back home.

Some might argue that the adage “show, don’t tell” falls short when applied to contemporary literature, which emphasises the interiority of its characters. But that comes with the caveat that the characters’ point-of-view or narration must captivate the reader. Unfortunately, The Silk Route Spy doesn’t achieve either. What the book seems to be concerned with instead is telling a perfect story of a conflicted but nonetheless almost perfect man — the adjective ‘almost’ so waifish it might disappear.

A non-fiction book written in the style of a novel cannot and should not shrug off the burden of pacing

Marketed as ‘non-fiction’, Sengupta writes the book from memory of the stories her husband has told her about her grandfather, who also speaks from memory of the stories that his grandfather told him, who also — you can see where I’m going — spoke from memory. This triple rebinding of Nandu’s story doesn’t seem to affect the book at all, which is a missed opportunity. A narrator who doesn’t insist on a neatly packaged approach is far more interesting.

Each part of the novel is divided into the many places that Nandu lived in during his tenure as a spy, from Amritsar to Kolkata to Kobe (in Japan). And although Sengupta can transport the reader to some of these locations, the descriptions don’t go beyond what you might know of the place from an internet search. They’re not lived in, even when the narrative insists that Nandu is a spy who knows his way around, making the reader a tourist and not a traveller.

A non-fiction book written in the style of a novel cannot and should not shrug off the burden of pacing. In the chapter where Nandu confronts and pushes Asit, a junior clerk he suspects of foul play, the tension falls flat. When Asit admits to working with the revolutionaries, Nandu “tells him a story”, stating that their goal is the same. I say ‘state’ because the dialogue is sparse, and wherever it’s present, it’s overbearing, with characters often slipping into pseudo-monologues. There are, of course, a few exceptions, like the sentimental moment between Nandu and his father, who buys him a coat before he leaves for Amritsar:

Papaji cleared his throat and said, ‘I am not a rich father, or else my son would not have to travel far to earn 30 rupees a month. He would be preparing to go to a college in the city or abroad. I couldn't give you much, but here is a gift from me. It is a coat. It may not be the best or latest cut, but it will keep you warm. Whenever you wear it, you will feel our arms around you. I hope you like it. It is brown and will match your trousers and shirts.'

Although the prologue carries an urgency to narrate the story of a man long ignored by history — a familiar trope for this genre that loves to ‘unearth’ and ‘unmask’ — this approach turns into haste, where the author’s proximity to her subject restrains the rendering.

When Nandu arrives in Shanghai, he’s introduced to Lily, the owner of his boarding house and his guide to navigating high society. This training inevitably involves seduction from Lily, but what precedes it is Lily’s admission that she was “feeling disturbed”. This is almost lost against the foreground of the section, where sex with Lily necessitates dipping into the pool of nostalgia, thinking of Vimla, his first love, as if to attest that he’s not engaging in a plain one-night stand. Nandu can’t have sex casually because that would rupture the hagiographic portrait. In this instance, the non-fiction becomes a parable when it could have been something else altogether. What makes the sanctimony evident is that within the next four chapters, Lily is dead, murdered by the gang members who own the city.

Then there are the plot points that are quickly skipped over. Right after Nandu’s future wife, Aiko, is introduced, the reader watches him marry her within a few pages. A few pages later, we see him having children with Aiko. The question of how he has changed across these milestones isn’t considered. We are left in the dark. (Aiko, too, is subjected to a comparison to Vimla, and I suppose men do cling to their first loves, but it makes her come across less like a doppelganger — which I would have welcomed — and more like a superimposed character.)

Fiction as the perfect act of espionage

The Silk Route Spy ends with the explanation that the reader knows of Nandlal Kapur only because he told his grandson about his double life. Sengupta, perhaps without realising it herself, admits to her and her husband’s embellishments:

Nandu’s world was his grandson. He used to sit for hours and narrate to him tales of his colourful past. The child understood only some of it, but he waited patiently for his grandfather to finish the story and give him a one-rupee note that would fetch him ice-cream lollies or roasted corn cobs.

What is the perfect act of espionage? I think it might be fiction. The form disguises profound answers within an often compelling narrative, either through plot or style. Like a covert operation, its full impact is only realised after the story’s stakes have been unravelled and possibly resolved. The Silk Route Spy is a compromised mission. Sengupta’s insistence on a sanitised, almost fable-like approach to her grandfather-in-law’s life undermines the potential for a truly gripping narrative, despite having all the right ingredients. You have a compelling historical context, a family mystery, and a double life shrouded in intrigue, but you still find it wanting.

Diya Isha is an editor at a Delhi-based publishing consultancy. You can find her on Instagram @contendish