Song Binbin, a student leader of China’s Red Guards who in 1966 was embroiled in the beating death of her high school principal, one of the most notorious killings of the Cultural Revolution — and who publicly apologised for her actions almost a half-century later — died on September 16. She was 77.

Her death was reported by a brother, Song Kehuang, on the Chinese app WeChat, saying she had died in the US. He provided no other details.

News of her death set off a renewed debate on Chinese social media about the adequacy of Song’s tearful apology in 2014, as well as the Communist Party’s failure to acknowledge the true toll of the Cultural Revolution, the decade-long rampage that Mao Zedong unleashed in the 1960s, claiming more than one million lives, and that remains a heavily censored topic in China.

Daughter of a prominent general in the People’s Liberation Army, Song was enrolled at Beijing Normal University Girls High School when she and classmates responded to Mao’s call for young people to turn against intellectuals, educators and others who supposedly held bourgeois values.

On August 5, 1966, students attacked Bian Zhongyun, a 50-year-old mother of four who headed the school. She was kicked and beaten with sticks spiked with nails. After passing out, she was thrown onto a garbage cart and left to die.

Her death has been widely described as the first killing of a teacher during the Cultural Revolution, a violent spasm establishing Mao’s cult of personality, with masses waving the Little Red Book of his writings.

In August and September 1966, nearly 1,800 people died in attacks by Red Guards, a militant youth group, and other zealots across Beijing, according to party estimates published in 1980.

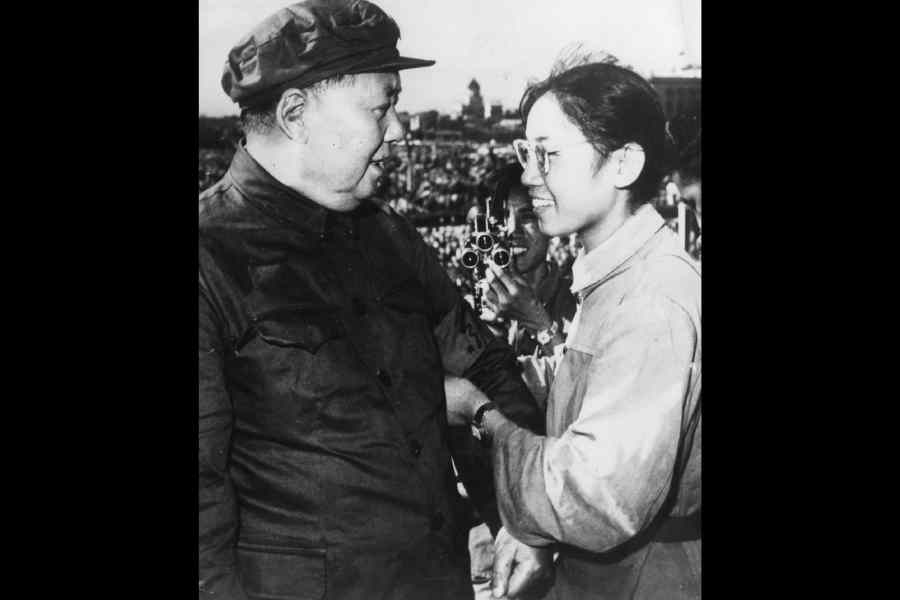

Two weeks after Bian’s death, more than one million young Red Guards thronged Tiananmen Square, where Song had been selected to pin a red armband around Mao’s

left sleeve as they stood atop the towering Gate of Heavenly Peace. A photograph of the moment appeared across the country. Praised by Mao, Song, at 19, became a kind of celebrity in China.

But the whirlwind of the Cultural Revolution soon turned on Song’s family. Her father, Song Renqiong, was purged from the Communist Party in 1968, and Song Binbin and her mother were put under house arrest. The Cultural Revolution ended only when Mao died in 1976.

Song, whose family regained its prominence among China’s elite, travelled to the US, where she earned a master’s degree in geochemistry from Boston University in 1983 and a PhD from MIT in 1989. She changed her name to Yan Song, married, became a naturalised US citizen and worked for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection.

She moved back to China in 2003.

For many years, Song kept quiet about her days in Mao’s Red Guard, reflecting the official silence about the period. But given her former prominence, she faced pressure to speak as a trickle of other former Red Guards began apologising.

On January 12, 2014, Song visited her old school and expressed remorse, bowing before a statue of Bian and delivering a 1,500-word speech. “I am responsible for the unfortunate death of Principal Bian,” she said, according to The Beijing News. (Bian’s title was officially deputy principal, but she was referred to as the principal because she was serving in that role at the time in an acting capacity.)

In 2004, Wang Youqin, a schoolmate of Song’s who later became a historian at the University of Chicago, published Victims of the Cultural Revolution, a book that included a description of the death of Bian and of Song’s role in the turmoil at the girls’ high school.

After Bian’s death, Wang wrote: “Every school in China became a torture chamber, prison or even execution ground, and many teachers were persecuted to death.”

Song denied that she had participated directly in the beating; she said, in fact, that she had tried to stop others who did. But she acknowledged that she and a fellow student were Red Guard leaders and that they were among the first to post so-called big-character posters — publicly displayed signs handwritten in a large format — denouncing teachers.

“The Cultural Revolution at Beijing Normal University Girls’ High School began when I participated in posting the first big-character poster on June 2, 1966,” she told The Beijing News.

Her apology prompted mixed reactions. Some Chinese welcomed her gesture; others said it was inadequate, too late or needed to be accompanied by a true reckoning from the Communist Party.

Some commenters stressed that Song should bear a greater burden because of her prominence among the Red Guards. “It’s meaningless to say you witnessed a murder and then say you don’t know who the killers were,” said Cui Weiping, a retired professor of literature who writes about China’s past, as quoted by The New York Times in 2014.

One person who was unsatisfied was Bian’s widower, Wang Jingyao. He had taken photos of his wife’s battered body after her death as well as of the posters that her tormentors had hung in their apartment after breaking in. One sign threatened to “hack you to pieces”, another to “hold up your pigs’ ears”.

“She is a bad person, because of what she did,” Wang told The Times in 2014, when he was 93. “She and the others were supported by Mao Zedong. Mao was the source of all evil. He did so much that was bad.”

Song Binbin was born in 1947, one of eight children of Song Renqiong and Zhong Yuelin, according to a family tree published by Bloomberg in 2012. Her father was one of the “eight elders” of the Communist Party who led the country’s economic opening after Mao’s death, acquiring wealth and influence.

Song Renqiong supported the Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping during the violent crackdown on protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989. Three of his six daughters left China in the 1980s for the US and became American citizens, according to Bloomberg.

Song Binbin married Jin Jiansheng, who was president of a Massachusetts company. He died in 2011. Her survivors include a son, Yan Jin.

At the time of her apology, when she was in her mid-60s, Song said that she had been anticipating it for some time.

“Failure to protect the school leaders is a lifelong pain and regret,” she said.

New York Times News Service