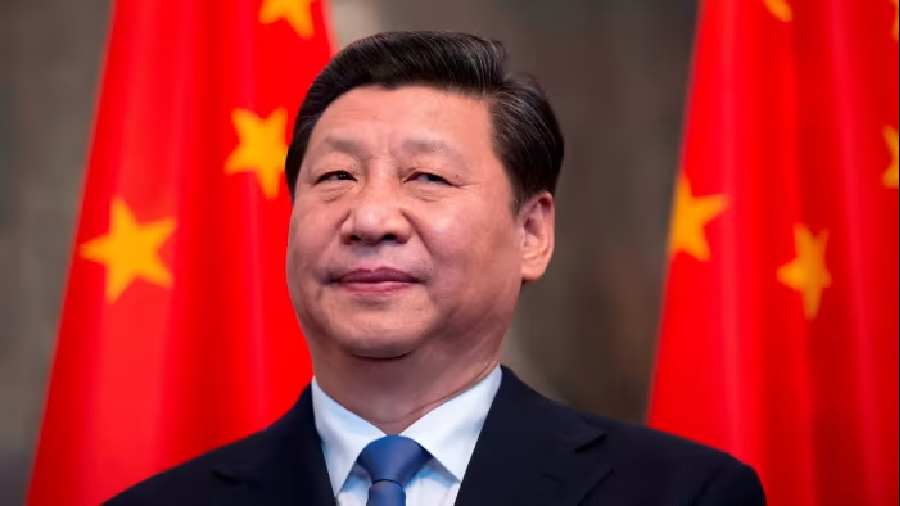

Under swarms of security, beneath clouds threatening rain, China’s leader, Xi Jinping, marked the 25th anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China with a showcase of just how thoroughly he had transformed and subdued this once-freewheeling city.

The police goose-stepped in Chinese military fashion at a flag-raising ceremony and showed off new mainland-made armoured vehicles.

The city’s streets were empty of the protesters who traditionally gathered by the thousands each July 1.

And Xi delivered a stern admonition that the open dissent and pro-democracy activism that had roiled — and, in many ways, defined — the city in recent years are things of the past.

“Political power must be in the hands of patriots,” he said, after swearing in a new leader for the city, a former policeman who led the crackdown on huge anti-government protests in 2019.

“There is no country or region in the world that would allow unpatriotic or even treasonous or traitorous forces and people to take power.”

The day’s ceremonies would have been momentous in any case, marking the halfway point in the 50 years that China promised Hong Kong would remain unchanged after the end of British colonial rule.

But they took on special significance as the first time that Xi had visited the city since the furious, at times violent protests of 2019, and since he launched a sweeping and successful assault on civil liberties in response.

In the last three years, the authorities have arrested thousands of protesters and activists, imposed a national security law criminalising virtually all dissent, and barred government critics from running in elections.

The anniversary also coincided with one of the most fraught geopolitical moments China has faced in recent history.

Its relations with western democracies have become badly frayed, including over its treatment of Hong Kong and friendly relationship with Russia. And tensions over Taiwan, which China claims as its territory, are escalating. Xi is only months away from an important Communist Party Congress when he is expected to claim an unprecedented third term and cement his status as China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

In that sense, Xi’s visit was at once a declaration of victory over the opposition in Hong Kong, an assertion of power to viewers at home, and a warning to his critics abroad.

“The case of Hong Kong makes clear that challenges and subversions of China’s core national interests inevitably will meet with serious counterattacks, and ultimately will fail,” Tian Feilong, an assistant professor of law at Beihang University in Beijing, and a prominent hawkish voice on the central government’s Hong Kong policy. Xi has taken a far harder line on Hong Kong than his predecessors had done. Hong Kong had long been home to vibrant civil society and protests — many directly critical of the Chinese government — but during Xi’s last visit, on the 20th anniversary of the handover in 2017, he for the first time laid out a “red line”. Any perceived threat to the central government’s sovereignty would “never be permitted”, he said.

New York Times News Service