Jane Goodall nursed a glass of neat Irish whiskey. It was the end of a long day of public appearances, and her voice was giving out.

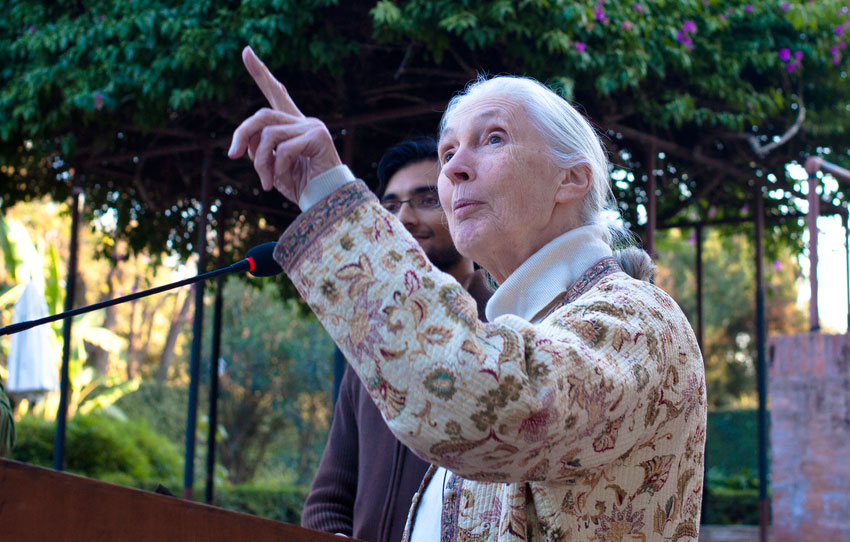

That’s what Goodall does these days. She talks. To anyone who will listen. To children, chief executives and politicians. Her message is always the same: the forests are disappearing. The animals are going quiet. We’re running out of time.

Goodall, the celebrated primatologist, was in New York as part of her ongoing efforts to raise money for her institute and its affiliates. The non-profit organisation raises money for conservation efforts across Africa, and works with local communities to promote economic self-sufficiency and improve public health. It’s proven to be an effective model for preserving chimpanzee habitats, yet Goodall is worried it’s not working fast enough.

“One million species are in danger of extinction,” she said.

Her faltering voice was the result of arduous travel and relentless campaigning. Yet her energy didn’t flag. For more than an hour, Goodall, 85, spoke about her family history, her unconventional career path and how business leaders — and consumers — can make a difference. This interview was condensed and edited for clarity.

Where’s home for you these days?

Mostly hotels and airplanes. But I’ve got a home in England. It’s that house I grew up in. It belonged to my grandmother, she left it to her three daughters and they left it to me and my sister. The condition is that if any of the family doesn’t want to inherit the house, it can’t just be sold. Everybody has to agree for it to be sold.

What did your parents do for work?

My father was an engineer. As soon as World War II was declared, he joined up and went to build Bailey bridges in Burma. My mum looked after us. For some reason, Pa wanted me and my sister to grow up learning French. So he hired a house in Le Touquet. We’d been there about three months and war broke out. So that was the end of learning French. I think we got the last civilian boat out.

What was your first job?

My very first job was with my aunt who was a physiotherapist. She had a clinic, and I would go there and take down the notes when the doctors were examining her patients. I learned a lot there about how lucky I was to be born healthy.

And I’m so glad I grew up in the war. Children today, they take everything for granted. We had two little squares of chocolate — that was our ration for a week. One egg. We used to get food parcels from Australia, and the only time we were allowed to eat any of them was when an air raid lasted longer than an hour. I can remember opening a tin of peach halves.

In the war, you learned to take nothing for granted. Even continuation of life. My father’s brother, Rex, joined the air force and he was killed. That was a big blow to Mom, because they really liked each other a lot. I sometimes think she’d rather have married him than my father. One day we were in Bournemouth in the evening and suddenly she screamed, “Rex!” and started sobbing hysterically. And it was the very moment he was shot down over Egypt.

The war clearly affected you quite deeply.

I remember seeing the pictures from the Holocaust, and that completely changed my whole understanding of humans. It was shocking, shocking. I remember climbing my favourite tree in the garden, a beech, and looking at these pictures and thinking, How could anybody do this?

But here again, my mother was clever. Of course we hated the Nazis, and thought everything to do with Germany was horrible and evil. But after the war, my father’s sister married someone who was sent out to be in control of the British sector of Germany. So Mom sent me off to live with a German family, because she wanted me to understand Germans weren’t evil, it was the regime.

When did you know you wanted to make working with chimpanzees your life’s work?

I don’t know that I thought of it quite like that. There was no thought of becoming a scientist, because girls weren’t scientists like that in those days. And actually, there weren’t really any men going out there, living in the wild. So my model was Tarzan. I saved up my pennies, and spent hours and hours in this little second-hand book shop, and had just enough to buy this little book, and that was when my dream began. I will grow up, go to Africa, live with wild animals and write books about them.

How did you make it happen against such long odds?

When I dreamed of Africa, everybody laughed at me at school. How would I do that? We didn’t have money. Africa was far away. It was the Dark Continent in those days, and I was just a girl. But my mom said, “If you really want this, you’re going to have to work really hard. Take advantage of every opportunity, and don’t give up.”

When you finally got into the field, how did you approach the work?

I didn’t have any academic training, and so I didn’t have this reductionist way of thinking. But fortunately I just applied common sense. I knew that to find out about the chimps, I would have to get their trust. And that took months. They ran away. They’re very conservative.

I came to understand how like us they are. I knew their different personalities, almost like members of my family. I’d seen them using tools and making tools, and it was clear they had emotions like happiness, sadness, fear. That they had a dark and brutal side, but also love, compassion, altruism.

Did working with chimps teach you anything about humans?

That we’ve been very arrogant in thinking that we’re so separate. Chimps turned out to be, not only behaviourally so like us, but also biologically like us, sharing 98.6 per cent of DNA, similarities in immune system, blood composition, anatomy of the brain. We’re not, after all, separate from the animal kingdom. We’re part of it.

Did becoming an activist come naturally to you?

No, I was very shy. It happened because I helped organise this conference in 1986. The purpose was to find out if chimp behaviour might differ in different environments, or is it so innately chimp that you find it everywhere.

But we also had a session on conservation. And in all of these sites, forests were going, chimp numbers were dropping. It was the beginning of the bush meat trade, of chimpanzees caught in wire snares, losing hands and feet. Poachers shooting mothers to steal babies to sell as pets overseas, or training for circuses. The human population was growing, moving deeper into the forest with their diseases, to which chimps are susceptible, but haven’t built up resistance.

We also had a session on how chimps are trained for the circus, medical research, labs. After seeing that secretly filmed footage from a medical research lab, I couldn’t sleep. I went to the conference as a scientist, and I left as an activist.

What have you found to be some effective strategies to promote conservation?

When we went to find out about the chimps’ problems in Gombe, Tanzania, we also learned about the suffering of the people — poverty, lack of health care and education. They needed to find ways that they could make a living without cutting down the last trees in their desperate effort to either grow food or make charcoal.

So we set up micro credit, based on the work of Muhammad Yunus, and we quickly saw the effect on the women. We then got money for scholarships to keep girls in school, during and after puberty. We started restoring fertility to the overused farmland, bringing in better health education and family planning information.

Now they love us, and they have agreed to put up a buffer zone between Gombe and the villages, and now they’re creating corridors for the Gombe isolated chimps to interact with other chimpanzee groups. And if you fly over Gombe today, there are no bare hills anymore.

What’s your message to business leaders today?

One million species are in danger of extinction. So what I say to the business community is: Just think logically. This planet has finite natural resources. And in some places, we’ve used them up faster than Mother Nature can replenish them. How can it make sense if we carry on in the way we are now, with business as usual, to have unlimited economic development on a planet with finite natural resources, and a growing population?

But consumers, at least if they’re not living in poverty, have an enormous role to play, too. If you don’t like the way the business does its business, don’t buy their products. This is beginning to create change. People should think about the consequences of the little choices they make each day. What do you buy? Where did it come from? Where was it made? Did it harm the environment? Did it lead to cruelty to animals? Was it cheap because of child slave labor? And it may cost you a little bit more to buy organic food, but if you pay a little bit more, you waste less. We waste so much. And eat less meat. Or no meat. Because the impact on the environment of heavy meat eating is horrible, not to mention the cruelty.