The year was 1982. The Mithun Chakraborty-starrer, Disco Dancer — a film about a street performer who goes on to become a big star — was the season’s big hit. Manik Das, all of 10, devoured it at a street corner, off a VCR (video cassette recorder). The number, Goron ki na kaalon ki/Duniya hain dilwalon ki, sung by Suresh Wadkar got burnt in his brain. Says the 47-year-old, “I started to dream about becoming a singer.”

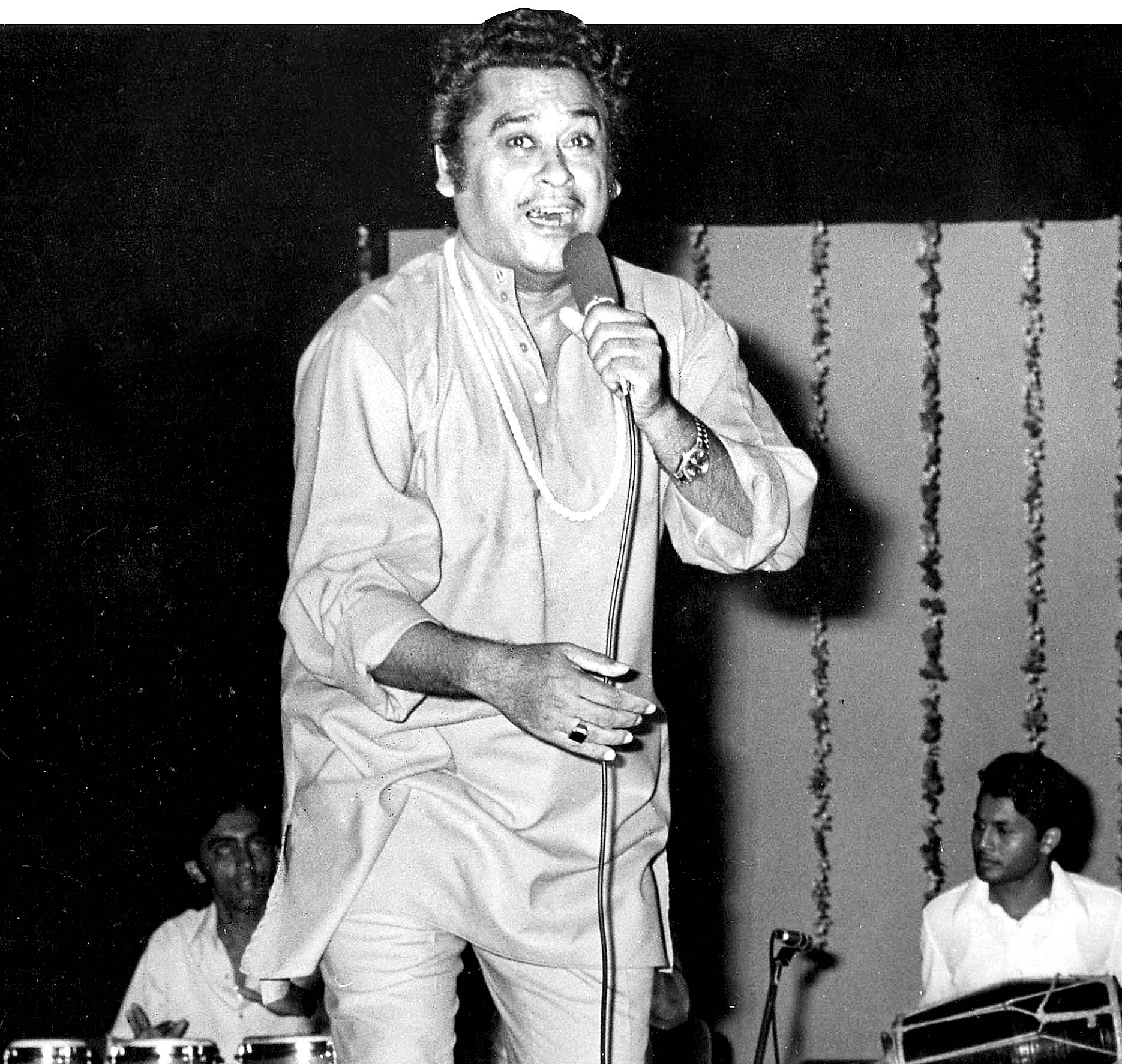

Manik is a chai-wallah or tea-seller in north Calcutta’s Tala Park. No, he does not own a shop or a kiosk, instead he makes several rounds of the park with his bucket full of paraphernalia and three flasks between 3 in the afternoon and 7 in the evening. Rs 5 a cup. Occasionally, he is invited to sing the golden numbers of Mohammed Rafi or Kishore Kumar at social and religious dos, mostly conducted by local clubs.

Manik was born into a lower middle-class family in Calcutta in the early Seventies. His father owned a small pen factory and his mother was a housewife. He had two brothers — one older and another younger. Bengal was in a state of turmoil those days, what with the Naxalite movement and the corresponding social unrest and joblessness.

This cha-wallah is clearly not in the habit of talking about himself, so when he does begin to, he tends to be overwhelmed by the memory of specifics. Specifics branch into more specifics. The storyline has to be rescued time and again, chronologies have to be sorted out, tales within tales disentangled.

Manik could not complete his education. He says, “I studied up to Class IV and then I shifted to a night school.” But he appears to have no regret for this. “Music has given me all the calm and happiness I could have ever asked for.”

Raring to venture out into the city, life itself was an education for Manik. Days passed and Manik started working in his father’s pen factory. “We used to make pens, create the labels, everything. In a small room adjacent to our house, we had installed the pen-making dice made of cast iron.” The small business was enough to feed a family of five. The Das family supplied the products to the wholesale market in Burrabazar. But then technology changed. And the entry of the use-and-throw pens decimated the family business.

Next, Manik landed a contractual job with the fire services department. “We had to carry those giant pipes. It was a strenuous job, but it fetched us a moderate earning,” says Manik. Then, one day he injured himself while carrying the pipes — fractured the hip bone. He says, “I understood I wouldn’t be able to do such strenuous jobs any more.” This time, he got himself a job to bind books at a printing press.

All along, it was clear that Manik had a gift, a musical gift, but there was no scope to indulge it. Nevertheless, when every other job turned out to be a dud, Manik thought of joining a music school. It is not clear from his responses if he did so with a career option in mind. Once again, specifics crowd the narrative. Time. Place. Venue. Finally, after scratching his head for a good while, Manik says, “I cannot remember his name, but there was one particular teacher who told me to get a harmonium.”

Manik managed to get one from a para dada, and after a couple of lessons he shifted to a more reputed school. And it is there that his musical journey, at least the training bit, came to an abrupt halt very soon after it had begun. “One evening I just couldn’t wrap my head around a certain tune and the teacher said, ‘You are the most dull-headed person I’ve ever come across. Music is not your cup of tea’.” Traumatised by the harsh reprimand, Manik never went back to any music school again.

For as far back as he can remember, Manik’s mother was ailing. From his details of behavioural specifics, I gather she had some kind of degenerative psychological issue. She was admitted to a mental home, but despite medical intervention things went from bad to worse. Recalls Manik, “The doctor suggested electroshock therapy, but she didn’t respond to the treatment.”

And then one day, after she was brought home, she went missing. He says, “It was 1993. I looked for her frantically, registered a missing diary, spent days visiting police stations and morgues — but in vain. To date, there is no trace of my mother.” The loss was a blow to the family, and for a while Manik became musically impaired as well. He says, “Eventually, I realised, music alone can solder the vacuum in my life.” Around the same time, he started to sell tea for a living.

I have heard Manik sing in front of a Shitala temple in Paikpara. The day I approach him for this interview, he is singing a Kishore Kumar number from the Eighties film, Sharaabi. He is sitting on a bench, eyes closed, singing: “Manzilon pe aa ke lutte hain dilon ke kaaravaan/Kashtiyan saahil pe aksar doobti hain pyaar ki/Manzilein apni jagah hain raaste apni jagah…” It has just drizzled a bit, and the trees in the area look scrubbed clean.

Manik has a good voice. His Hindi diction is surprisingly clear, there is not a shadow of a Bengali accent, not in this case at least. But perhaps most importantly, there is a pathos that imbues his rendition and catches the bystander’s attention.

It seems, so long as Manik was chasing the stage, he had no takers. He met local dadas and politicians and solicited for opportunities, but nothing seemed to work. He continued to be the butt of jokes in his immediate social circle for even harbouring such a tall aspiration. And then one day, just like that, opportunity knocked. He got a chance to sing on a makeshift stage in Paikpara.

Says Manik, “I sang Ke pagh ghungru bandhe Meera nachi thi... That day, when I heard the audience clapping and cheering, I realised I had not been wrong about myself. I realised that I may not be Disco Dancer, but I could sing.”

I ask him why he sings mostly Kishore Kumar songs — he also sings several Rafi and Hemanta Mukhopadhyay numbers — and he starts to talk about his style, his ability to capture the mood of a song, his voice throbbing with emotion. He speaks of the late singer as if he were less man more god. And yet it will be wrong to call him a Kishore Kumar clone.

Soon after the Paikpara show, Manik started to receive calls from many clubs in north Calcutta. Now he has a regular clientele. But no, this is no rags-to-riches story. Manik’s mainstay is the tea business, it is what feeds his family — wife and two daughters — and his younger brother’s. But he is not cribbing.

As will sometimes happen, from singing the songs of a hero, Manik has unconsciously taken on his heroism. He tells me how much he charges for an evening’s performance, and with a flourish adds, “Money is no bar.” He then breaks into a song, “Main zindagi ka saath nibhata chala gaya/Har fikar ko dhuen mein udata chala gaya…”