On Sunday, FM radio, social media slickers, TV reality show experts and many more would be celebrating the 90th birth anniversary of Kishore Kumar. Nothing unusual about it, just that for someone who died at 58, the 90th anniversary celebration will not exactly be through nostalgia-coated glasses. Occasional exceptions apart, Kishore Kumar the singer-actor-entertainer-human being never became part of the nostalgia gravy train. His legacy — especially his songs — has survived his life and times many times over. Like Chaplin, Hitchcock or Ray, Kishore remains one of the few who gave the term “generation gap” a deflated ego. And it continues to be like that. As Vir Sanghvi had put it while talking about the 1970s — “There is little nostalgia for the playback singers of the Sixties, but Kishore Kumar remains as popular today as he was during the Seventies.” Period.

The popularity Kishore gained in early 1970 with the graph rising steadily till his sudden demise in 1987 was not without precedence. While Kishore had struggled, and literally so, for two full decades before suddenly hitting the jackpot to success, the 1950s had him at his zaniest, running from studio to studio, working in multiple shifts as a part comedian, part hero, in films that would do well commercially then but would mostly be termed as inconsequential by critics. Kishore was no fool, he knew that Bombay cinema was all about being in the rat race. So even when a few of his songs got dubbed by Mohammed Rafi and Manna Dey, Kishore refused to contemplate beyond a point. He continued acting. And singing the one-oft song, for Dev Anand and himself —mostly.

However, he was still not viewed as a serious singer. The number of songs he sang in the 1950s was less than 170, though one might note that he had cut down his singing assignments considerably starting 1957.

Maybe he knew his time would come.

He also tried the not-oft-trodden rule by singer-actors with a moderate amount of success. Filmmaking. His films had the proverbial disclaimer — avoid it. Forget reassessing his work, few viewed a Kishore Kumar production — barring Door Gagan Ki Chhaon Mein (1964) — with any seriousness. It was probably the accumulated hurt which made him pay a tribute to his first Hindi production Chalti Ka Naam Gaadi (1958) with the mad sequel Badhti Ka Naam Dadhi (1974). This meaningless mockery in the name of cinema was actually what he wanted to say — look, this is how films are made in Bombay. Forget any semblance of logic. This is something I had to do as an actor working under irresponsible, inept filmmakers.

No wonder he had confided to Pritish Nandy in the famous Illustrated Weekly of India interview, published in April 1984, that he did not have the good fortune of working under respectable filmmakers barring Bimal Roy and Satyen Bose.

The 1960s started on a bad note. A divorce which happened in 1958-59, followed by marriage to a terminally ill Madhubala, something which demanded his time, energy, and infinite patience. His films, both good and bad, started failing. No longer the comic in him was saleable. The only viable alternative was to go back to his first love — singing. It was probably providence that forced him out of the self-inflicted hibernation. The Anands (Dev and Vijay) were eager to have him sing in Guide (1965). Gaata Rahe Mera Dil relaunched his career as the voice of Dev. Later, Vijay Anand and SD Burman both gave press statements that they wanted Kishore to sing for Dev. Always. From Teen Deviyan (1965), he was back on track.

He had other well-wishers too. The singing fraternity — Lata, Asha, Rafi, Manna, Hemanta, et al — loved him. And Rahul Dev Burman would remain his biggest fan for life.

It was around the latter half of the decade that composers Kalyanji and Anandji gave him a suggestion. Kishoreda, you are such a good singer. Who don’t you concentrate on singing? Why waste time standing in front of reflectors sweating and shooting trivial stuff?

The words stuck. Probably this was something Kishore actually wanted to hear somebody telling him.

And then Aradhana (1969) happened. Sachin Dev Burman had spoken his mind. Javed Akhtar, a die-hard fan, in his conversations with Nasreen Munni Kabir mentioned that Kishore was the voice of the city slick, driving motor bikes. While it was not a bike, but a jeep on the road to Darjeeling which took his fortunes to Himalayan heights, Mere Sapno Ki Rani became the anthem of the bike-riding early 1970s. The elusive hit which Rajesh Khanna was waiting for happened in his sixth film. The impact was too strong for any conventional, tried and tested adjectives. The word “Superstar” was coined. And when the superstar drove a bike, lip-synching to Kishore’s melodious and fun-laden yodelling-scatting Zindagi Ek Safar Hai Suhana (Andaz), it was almost that the old guards — Shammi Kapoor and Md Rafi — were catapulted out of the frame of stardom. Kishore Kumar had become an overnight sensation.

The reaction to this unexpected and extraordinary rise was not very cool.

Film magazines received readers’ letters complaining about a certain Kishore Kumar who used to sing nice-to-hear songs at times in the 1950s and the 1960s now having become the toast of the mikes around the entire geography of the country. Unfortunately, the propaganda did little to deter Kishore from achieving superstardom.

Almost overnight.

Incidentally, detractors hardly had a clue about the conditions in which Kishore had recorded the songs which celebrated the creation of two super powers in Hindi cinema. Most of the songs of Aradhana were recorded when Madhubala was critically ill (Roop Tera Mastana on June 17, 1968; Mere Sapno Ki Rani on August 28, 1968, and Kora Kaagaz Tha Yeh Man Mera, July 30, 1968). Kishore’s first concert-trip to the US, planned for April 1969, almost got cancelled when Madhubala passed away in February of that year. Kishore’s recordings came to a grinding halt. This led to complications with huge financial implications. One such delay led producer-director Raj Khosla to request Kishore to sing for a film which was in the pipeline — a day before Kishore’s trip to the US. Subsequently, Film Center was booked for a day. Kishore came down, rehearsed a tune created by Laxmikant to the lyrics of Anand Bakshi, and sang to the arrangement of Pyarelal. All of this happened in a day. The song is the evergreen classic Mere Naseeb Mein Ae Dost (Do Raaste, 1969).

Today, Kishore’s songs in Aradhana (1969), Do Raaste (1969), Khamoshi (1969), Safar (1970), Kati Patang (1970), Amar Prem (1971), Haathi mere Saathi (1971), Dushman (1971), Apna Desh (1972), Mere Jeevan Saathi (1972) etc. are as popular as they were then. If Rajesh Khanna was the superstar, Kishore was the super-singer. Khanna’s crown would be soon dismantled. Kishore remained the superstar singer ever after.

After that, Kishore sang around 2,000 songs.

The total count is estimated to be between 2910-2950. Going by statistics received from RJ Arvind of 94.3 FM, Kishore Kumar’s popularity does not indicate any decline. He gets requests for over 100 every day.

Nostalgia? Forget it. He is current.

The writer is co-author of the National Award winning book R.D. Burman — The Man, The Music

RD Burman, Lata Mangeshkar, Kishore Kumar and Asha Bhonsle at a gathering From The Telegraph archives

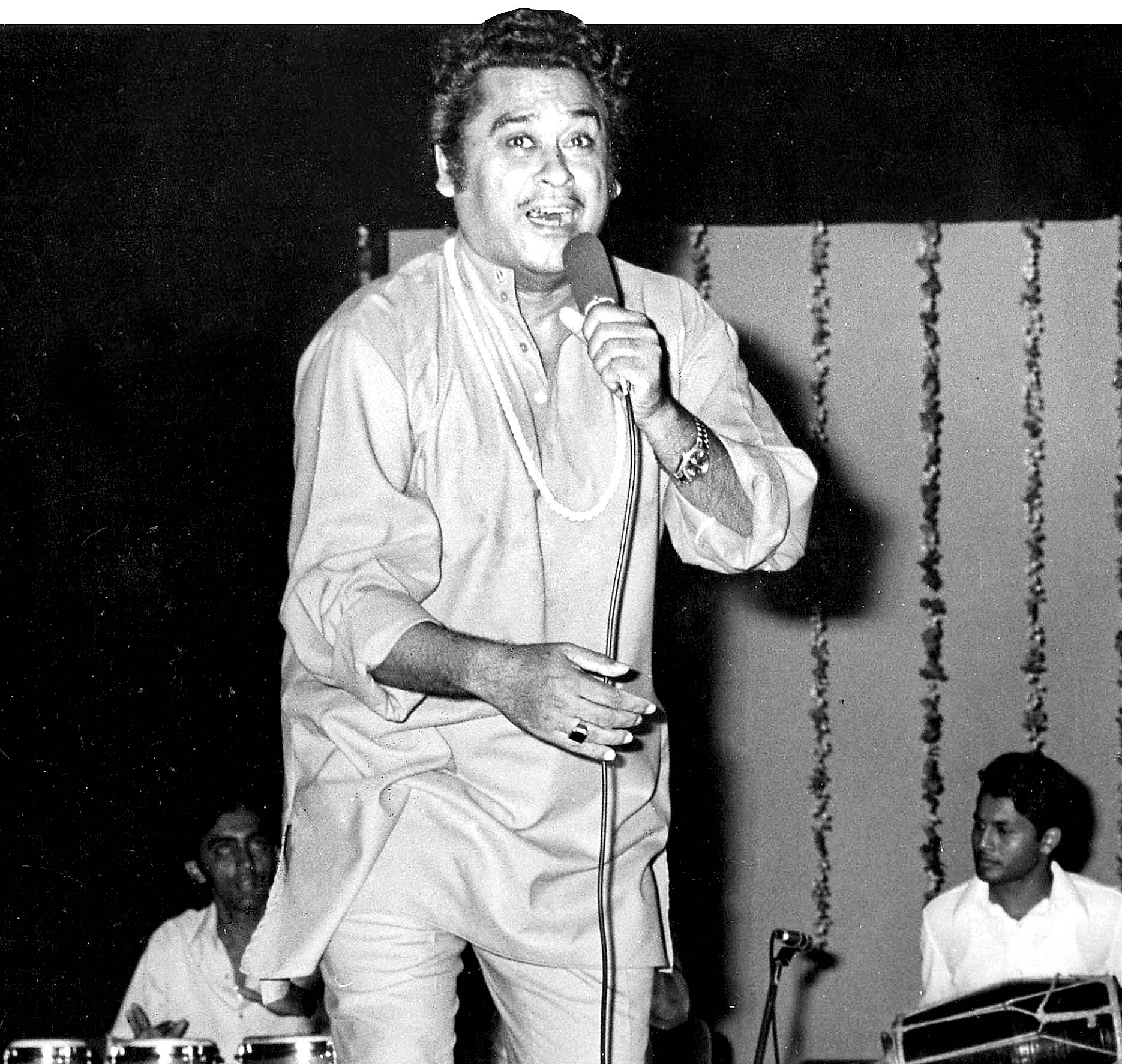

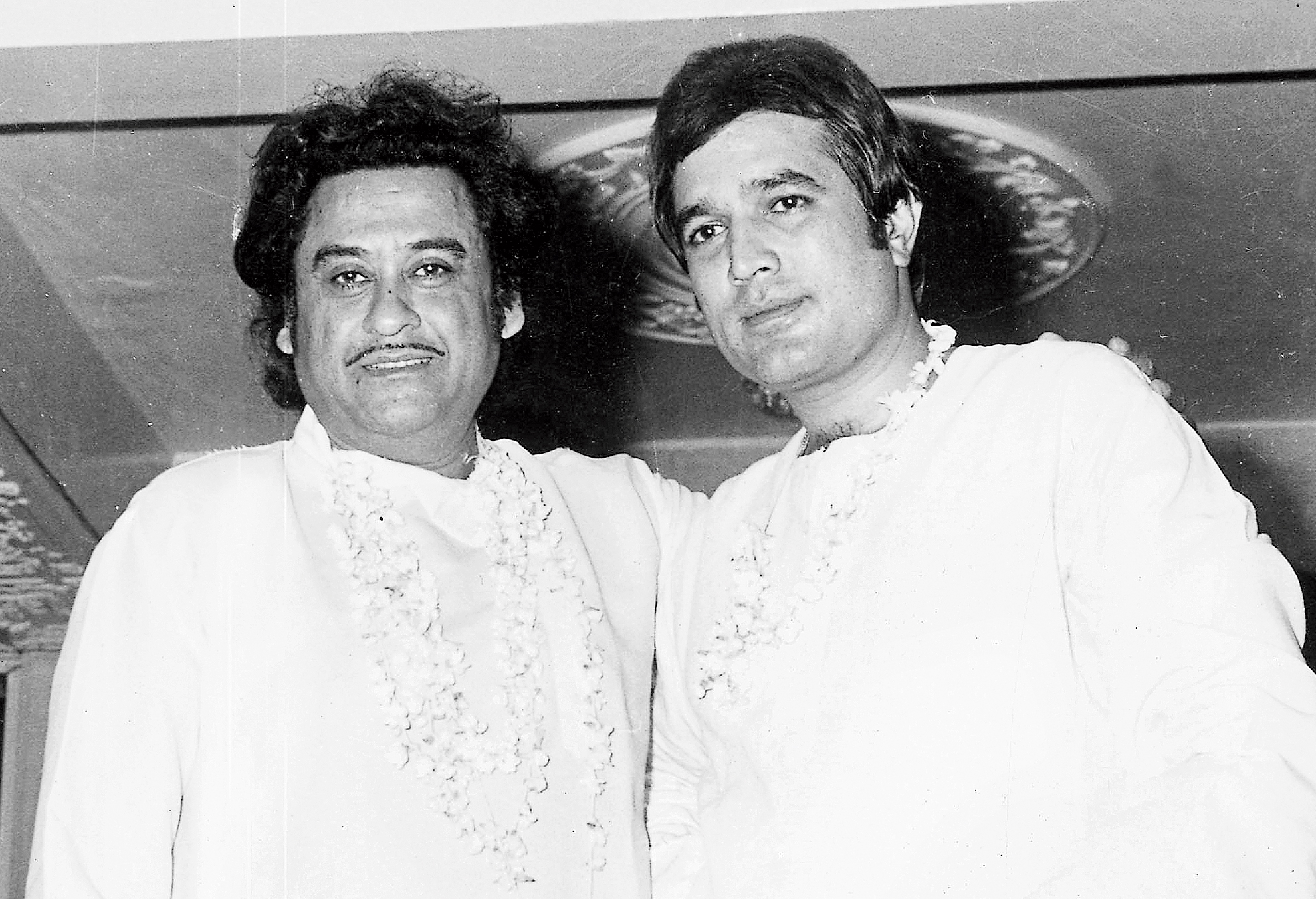

Kishore Kumar with Rajesh Khanna From The Telegraph archives