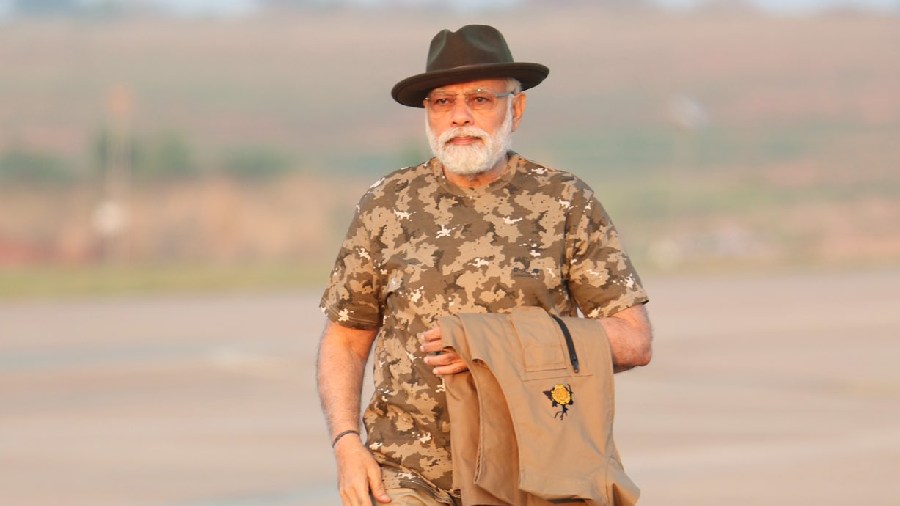

Commemorating 50 years of Project Tiger — India’s first species-centric, inclusive, conservation endeavour — recently in Karnataka, the prime minister, Narendra Modi, underlined his government’s steadfast adherence to the fine balance between ecology and economy. Mr Modi has perhaps based his claim on the findings of the latest tiger census. The quadrennial counting exercise revealed a rise in the minimum tiger count by 200 to 3,167. India now carries 75% of the global tiger population. Fittingly, Mr Modi also announced the launch of the International Big Cats Alliance, a 97-nation bloc that will focus on the conservation of seven big cat species in the wild — tiger, leopard, jaguar, lion, snow leopard, cheetah and puma.

Yet, the success must not make conservation policy indifferent to the challenges ahead. The findings in the census indicate several worrying anomalies. While the Shivalik range, Gangetic plains, and northeastern hills have witnessed substantial growth in big cat populations, local extinctions have been recorded from central India and the Western Ghats, even though the latter is one of India’s biodiversity hotspots. This can be attributed to the fragmentation of forest cover and the loss of prey base. The tiger population is expected to touch 5,000 in the course of this decade but most tiger reserves — the Sundarbans are an example — have reached their carrying capacity. This only heightens the possibility of sustained man-animal conflict. Moreover, heavy concentration of the species in specific sites also puts them at the risk of epidemics. The redistribution of tigers should be looked at. But this would require the creation of forests that are suitable to sustain new populations. Given the shrinking of dense forest cover — a manifestation of Mr Modi’s government prioritising economy over ecology — the relocation of India’s national animal would encounter significant problems. Saving the tiger or, for that matter, any wild animal cannot be looked at in isolation. It requires comprehensive, overlapping interventions involving the regeneration and protection of forests, their inhabitants as well as communities that share a symbiotic bond with the wild. It is a massive, layered challenge. India’s conservation policy must be ready to meet it.