It was a blistering day in 1982. The ground of the Boys School at Harippad, an agrarian town in Alappuzha district in Kerala, and its surroundings were flooded with people braving the raging summer. Suddenly, the roar of an approaching helicopter was heard, which was immediately overwhelmed by the loud cheering of the crowd chanting, “Indira... Indira... Indira...” The enthusiasm of the crowd had hit a crescendo.

As Indiraji alighted from the chopper and waved at the mammoth gathering, the effect was magical. That was my first glimpse of a Gandhi. I was 26, and it was the first time I was contesting an assembly election. Indiraji had come to campaign for me. I still cherish those fond memories of the charismatic leader who then spoke in a language of love and determination. When I left for Chennithala, my village, after the meeting was over, I had no idea that the event would turn out to be a milestone in my life; I also had no idea that Indira Gandhi would be instrumental in changing my destiny from then on.

It was by chance that I became an active worker of the Kerala Students Union during my college days, and my rise up the organizational ladder was phenomenal. Though professionally trained to teach Hindi in schools in Kerala, politics and serving humanity have always fascinated me. I became president of the KSU in 1980 with the backing and blessings of Kerala’s Congress strongman, K. Karunakaran, fondly called ‘Leader’. And it was in those days that I started interacting with the national leaders of the Congress Party and its various feeder organizations, especially Rajiv Gandhi, who was in charge of the National Students’ Union of India and the Youth Congress in his capacity as general-secretary of the All India Congress Committee.

I vividly recall that morning in 1982 when Karunakaran contacted me through emissaries while I was attending a KSU meeting at Koothuparamba in Kerala’s northern district of Kannur. ‘Leader’ conveyed the message that Rajiv Gandhi wanted to meet me in New Delhi immediately. I left for the national capital without any clue as to what would be discussed in the meeting.

In Delhi, I met Rajivji at his small but elegant residence where there was nothing extraordinary to indicate that it was the residence of the son of the country’s prime minister. Rajivji, clad in blue jeans and a white T-shirt, was looking out of the window of the drawing room. He spoke to me very lovingly for a few minutes. The talk mainly included queries about my journey and accommodation as well as the organizational work in Kerala.

Then, all of a sudden, he revealed to me his plan to appoint me president of the NSUI.

“I know you can do it and I will be with you,” Rajivji said as he held my hands. He said he was confident about my ability to handle Hindi and English and to work hard to rebuild the organization across India.

I was spellbound for a moment after hearing what Rajivji said. But soon I told him that I was ready to take up the task. Then he told me that he had already apprised Indiraji of the decision, which must be ratified directly between her and me. Until then, I had had no personal meetings with Indiraji; I had always watched her from a distance.

Then Rajivji took me to Indiraji. He drove the car straight to her residence. When we reached her residence, Indiraji was about to leave for the airport to board a flight to the erstwhile USSR. She was in a hurry. The AICC general-secretary in charge of the party organization, G.K. Moopanar, was there at the residence.

“Are you Ramesh Chennithala?” Indiraji asked me. I nodded my head.

“I know. Rajiv has already told me about you. I’m happy that you are ready for the task,” Indiraji said. Then she told Moopanar to prepare my appointment order quickly. While the stenographer started typing the appointment order, Indiraji left for the airport, directing me to reach the airport with the typed appointment order for her signature. It was at the airport lounge that she signed the order appointing me president of the NSUI.

I knew I was the personal choice of Rajivji for that crucial post — it was a time when he was initiating a big revamp of the NSUI and the Youth Congress.

As directed by Rajivji, I travelled the length and breadth of India, revamping the NSUI. I had mainly focused on Central universities.

It was in those days that we conceived the idea of organizing a huge student conference in Nagpur, Maharashtra, with an expected turnout of over half-a-million young workers of the Congress Party. Our idea was to make it India’s largest-ever youth meet. Even from distant Kerala, the southernmost state of the country, we chartered a train to carry over 1,500 party workers. The meeting was well-planned, and the preparations had begun well in advance. Great care was taken regarding food and accommodation for all participants. The announcement that the prime minister, Indira Gandhi, would address the concluding rally of the youth meet boosted the morale of the cadre considerably. Rajivji, who was present at the conference all the time, was ready to perform even humble tasks.

However, right from the beginning, we noticed a sort of an unrest among a section of the gathering. Things started getting out of our control when a sizable portion of the assemblage started complaining about inadequate accommodation and food. I doubted that somebody was wilfully provoking unrest to defame the NSUI in particular and the Congress Party in general. When I shared my suspicion with Rajivji, he took a vehicle parked outside the conference venue and asked me to board it. We went to the office of the person in charge of Nagpur railway station, and from there he contacted the Union railways minister and requested him to help us by providing the available accommodation and catering facilities of the railways in Nagpur. With the railways schools, guest-houses and empty buildings being turned into accommodation facilities, and with the railways canteens serving food, the unrest among the participants subsided and the conference turned out to be a huge success. The AICC paid the railways for the food and the accommodation facilities.

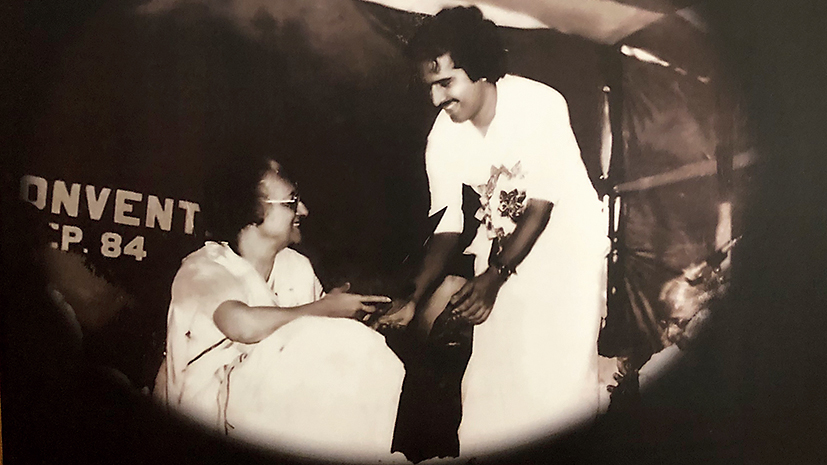

Indiraji reached the conference venue on the final day, and I welcomed her with a speech in Hindi. She congratulated me saying that a person from a non-Hindi-speaking state making a powerful speech in Hindi was a sign of national integrity and unity. Her vibrant speech infused a novel enthusiasm and vigour in all those present there.

Years later, the Thakkar Commission, which investigated the assassination of Indiraji by two of her security guards, said there were several attempts earlier to assassinate her, and one of them was in Nagpur. There were wilful attempts to create unrest and assassinate her during the road show amidst chaos, the Commission said. Only then did I realize the gravity of the risk involved at the Nagpur event.

Indira Gandhi was a noble soul with strong secular and pluralistic credentials. When the Intelligence wanted to keep the members of the Sikh community away from her personal security detail, Indiraji disagreed, saying that such a move would further alienate the community from the government, the party and the nation.

At 9.20 am on October 31, 1984, when her bodyguard, Beant Singh, fired from his gun into her body, Indiraji would not have felt disillusioned or chagrined. By not avoiding bodyguards of a particular community, she had chosen to risk her life rather than endangering the unity of the nation and she had chosen to die for the cause of unity. She always stood for the unity, integrity, solidarity and amity of the nation. Communal and casteist feelings were alien to her. She was a leader with truly pluralistic perspectives.

When the nation and its Constitution are facing threats from different sides, when a large section of society is being alienated in the name of citizenship, the memories of Indiraji are more relevant now than ever before.

My humble homage to the fond memories of Indiraji.

The author is a senior leader of the Congress Party and the leader of the Opposition in the Kerala legislative assembly