The world is perilously close to a nuclear conflagration.

Closer to it than it ever has been.

If it does not blast itself out in the coming days, weeks, and months, it will not be because great good sense has prevailed but because of that funny and fantastic thing called luck.

Am I a loonie to be saying this?

Read, please, dear reader, a book that appeared in March of the year that has just ended, Nuclear War: A Scenario by Annie Jacobsen. Or at least about it through various digital pathways, as I have done. The book is not about science, it is not a nerve-thriller. But it is not fiction. It is as much about things as they are, as the words you are reading are. The narration is not about some distant date of horror. It is about today, about the here and now.

North Korea, in the book, believing it is about to receive a fatal attack from the United States of America, decides to show its steel. It decides to unleash a missile strike against that country. Washington cannot but respond and does, by despatching 50 Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles to hit North Korea. One serious snag is that the US missiles, in order to reach in time, have to overfly Russia.

The US president wants to get through to his counterpart in Moscow but is unable to. No time is to be lost, so the missiles go hissing. The Russian president, outraged, does what he must: he orders a nuclear attack on the US. The rest should be read in Jacobsen’s words. It is beyond nightmarish because it is utterly real, totally as it could well be.

Last November, the lame-duck US president, Joe Biden, granted Ukraine permission to strike targets deep inside Russia with American-made weapons. Two days after Biden’s ‘permission’, on November 19, Dmitry Peskov, press secretary to the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, announced that Russia had revised its nuclear doctrine. Not that it was going to, or intended to, but that it has actually revised it. He was telling the world to take note of this. By this revision, said Peskov, if a non-nuclear country allied to a country with nuclear weapons was to hurt Russia, it could well get hit by Moscow with nuclear weapons. Russia’s chief of general staff, Valery Gerosimov, said on December 18, 2024 that, following increased activity by the US-led NATO military, arms control is for Russia now “a thing of the past”.

Ukraine’s penetrations into Russian space have escalated, Russia’s hits on Ukraine have multiplied. Action and reaction are on a par. If a Ukraine strike hits Russia where it hurts more than it has so far, then the new doctrine can unravel.

In less than ten days from now, Donald Trump will ascend to the office of president of the United States of America. Let me not burden the reader with my views on the subject and quote, instead, what in its end-of-year editorial The Guardian (London, December 27, 2024) has said: “Mr Trump admires strongmen like Russia’s Vladimir Putin, who has recklessly threatened nuclear strikes and hinted at restarting tests during the Ukraine war. But it would be a catastrophic mistake if the pair decided not to exercise self-restraint. It would mean that for the first time in more than 50 years, the US and Russia — holders of 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons — could begin an unconstrained arms race.”

The Ukraine-Russia war is not the only theatre of death today. The ballistics of the Israel-Palestine or the Netanyahu-Hamas logjam are a cobra’s hood over the world. The risk of escalation in and from Gaza, with non-State players sneaking into the scenario, is sky-high. No one in that theatre vows anything less than the imminent and total annihilation of the other. Is that zone nuclear weapons-free? Of course it is not.

Jacobsen’s scenario was never fictional. It is now about more than reality. It is the truth that stares us in the face, like any clock might, any clock that is ticking away to the midnight of devastation, where it may well ring ten… eleven… twelve before we can say ‘stop’.

What has India to say about this?

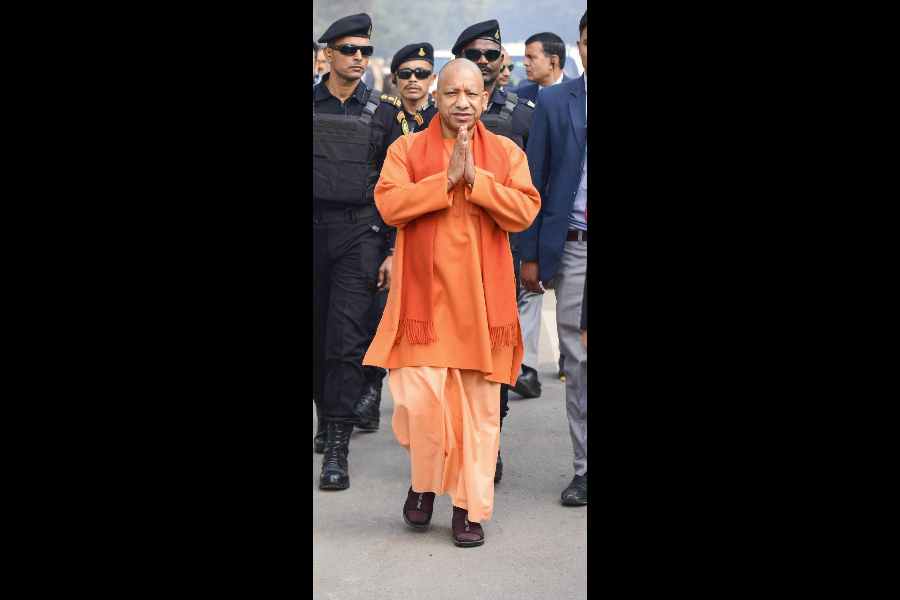

To be sure, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has spoken to all the relevant world leaders about the need for restraint, the criticality of dialogue, the dangers of escalation. But ‘India’ is not just the government. It is Indian thought, Indian opinion, Indian feeling. In other words, India’s pulse.

And what does that pulse tell us, what does it tell our government?

India’s pulse, rapid and emphatic on so many matters, is, on this subject of global life and death, feeble.

India is not fretting about the need to prevent a nuclear apocalypse.

To go by books sold in the English-speaking market in India, let us be sure William Dalrymple’s hugely readable The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World will outsell Annie Jacobsen’s hugely crucial Nuclear War: A Scenario by a margin so large as to make the latter almost invisible.

The fact that the Nobel Peace Prize for 2024 going to Nihon Hidankyo (The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organisations), for its activism against nuclear weapons, assisted by victims/survivors (known as hibakusha) of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in1945, has made no news in India astonishes me.

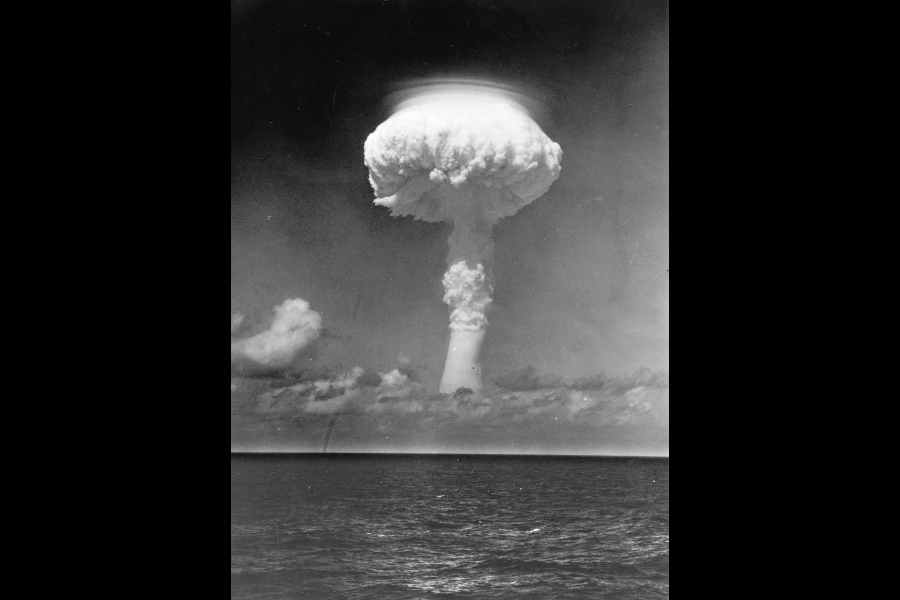

Is the fact, the burnt bone-hard fact, that what happened to the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with ‘the excoriated survivors envying the dead’, can happen to us, to our children, any moment, lost on us?

As to India’s engagement with Ukraine, as Indian students imperilled there by the war returned home to safety — a great feat of Indian diplomacy — that country’s war became for us ‘a war out there, somewhere’. There was a certain concern again when reports came of Indians working in Russia getting billeted into the war by Moscow, but when that — again by skilful Indian intervention at the highest level — was addressed, Ukraine lapsed into Indian inattention.

And when it comes to the dangers to all human life as a result of the war in Gaza, so hard-wired is India’s sentiment about international terrorism that the Israel-Palestine conflict is seen by it in unshakeably phobic terms.

The world is teetering towards possible nuclear suicide but we, in India, have seated ourselves in a posture of stoic detachment about that.

Arms control, whether on the subcontinent of India or in the world at large, is not a subject that occupies even a fraction of our attention as a people.

If a random set of us, the people of Bharat, was asked whether India should engage with its neighbours in talks on arms control, or go ahead, regardless, to weaponise to deter attacks, including terror attacks, the answer would most likely be, ‘Of course, weaponise’.

Will no one from among us, like scientists, strategists, and social philosophers, explain to us that a bomb dropped on belligerent ill-wishers in our neighbourhood will decimate them and us, not just by way of retaliation, but radiation? Einstein, Bertrand Russell, and about 10 other leading scientists addressed all the leaders in the Manifesto that goes by their names on July 5, 1955. They asked the nuclear-empowered and nuclear-able leaders to cease that perilous activity. “Remember your humanity, forget the rest,” they said.

This year, 2025, is the 70th anniversary of that Manifesto and the 80th anniversary of Hiroshima-Nagasaki. Can India not convoke a world conference of scientists and Nobel laureates to issue a fresh Manifesto, prompted by the new perils of an ‘un-constrained arms race’ and worse, of an actual nuclear Armageddon?

If India would like to be regarded as a ‘Vishwaguru’ (world teacher), it would.

But there is something more important (and less egotistical) than wanting to be ‘Vishwaguru’. And that is wanting to be and actually being a 'vishwarakshak' (world protector).