Sometime back, I found myself at a party, arguing with some friends about the the work of a certain documentary film-maker, X. Like me, one of the friends was also a maker of documentary and non-fiction films, and the discussion went into X’s craft and his engagement (or lack thereof) with form in his films. We agreed that X was an old-fashioned docu-activist whose only concern over the decades had been with the content of what he was documenting and the message, the political argument, conveyed by his films. It wasn’t that X lacked technical skill, it was just that he was supremely uninterested in using that skill to experiment with cinematic structure. At the end of a particularly challenging year, the pervasive feeling was that all sorts of things we had taken for granted were coming to abrupt termination. Looking a few decades ahead we came to the conclusion that people seeing the films of our time might well have very different criteria from ours. We accepted that X’s films would be extremely valuable for what they reveal about the realities through which we have lived and their formal aesthetics might not be very relevant. A couple of days later I got the news that Mrinal Sen had passed away and I found myself rewinding through this conversation.

Of the four fiction film-makers Bengali cinema has produced, to whom the over-used descriptors ‘towering’, ‘eminent’ and ‘great’ can be attached, Mrinal Sen was the last one surviving. Wikipedia reveals that all four directors were born just short of a century ago, Satyajit Ray in 1921, Mrinal Sen in 1923, Tapan Sinha in 1924 and Ritwik Ghatak in 1925. The youngest, Ghatak also died the earliest, at only 51; Ray followed, a too-early passing at 71, whereas Sinha (who, for some strange reason, people tend to exclude, concentrating only on the ‘triumvirate’) and Sen can both be said to have had a full innings. At the time of Ray’s death, people kept trotting out the cliché about it being the end of an era, but arguably this cinematic era could be defined from the first day’s shooting of Pather Panchali to the day Mrinal Sen completed his last film in 2002. Why not from when Ghatak made Nagarik in 1952, or Sinha’s Ankush of 1954? Because it was Pather Panchali that pushed serious Indian cinema to another level and forced the other three in the cohort to raise their game, though each in his own way. As for the end-point of the era, Ray-centric people would variously argue that the ‘golden period’ was over with Charulata, 1964, or stretch it to Shatranj ke Khilari, 1977 (in Hindustani, yes, but an honorary Bengali film, and often labelled as ‘the last good film Ray made’); Ghatakistas would stop at Ritwik’s last completed film, Jukti Tokko aar Goppo; yet others would point out that Tapanbabu continued to work till 2000; many would hold up the flag for Mrinalbabu, who continued to work till 2002.

The shortest of these four careers — Ghatak’s — lasted 21 years while the longest — Sen’s — stretched across almost half-a-century. During this time, each of these directors made films of varying quality, going through different influences while dealing with different historical and political moments. During this time, a favourite pastime of the Calcutta kinophile was to match up one director against the other as if they were tennis players or boxers. The directors themselves (with the possible exception of the reticent Tapan Sinha) were also quite outspoken about each other’s work, definitely in conversations if not always in print. This candour led to many apocryphal stories that reached the level of lore. Even though people of my generation missed out on the peak-period of the 1950s and 1960s owing to mistimed childhood, I’ve myself seen drunken brawls break out between people pulling for Satyajit and people backing Ritwik or Mrinal. With the departure of Mrinal Sen we can say that that period is now definitely over.

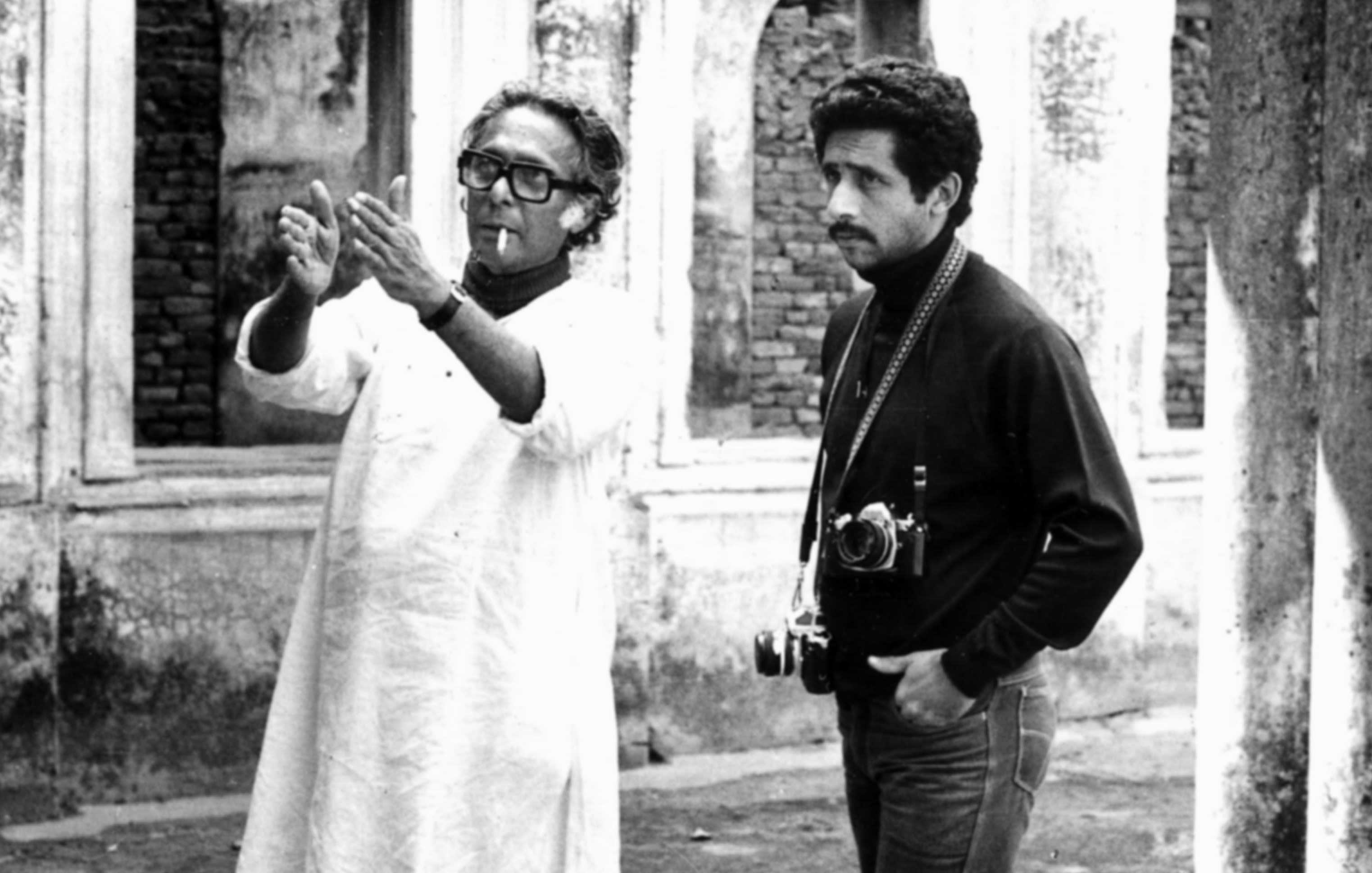

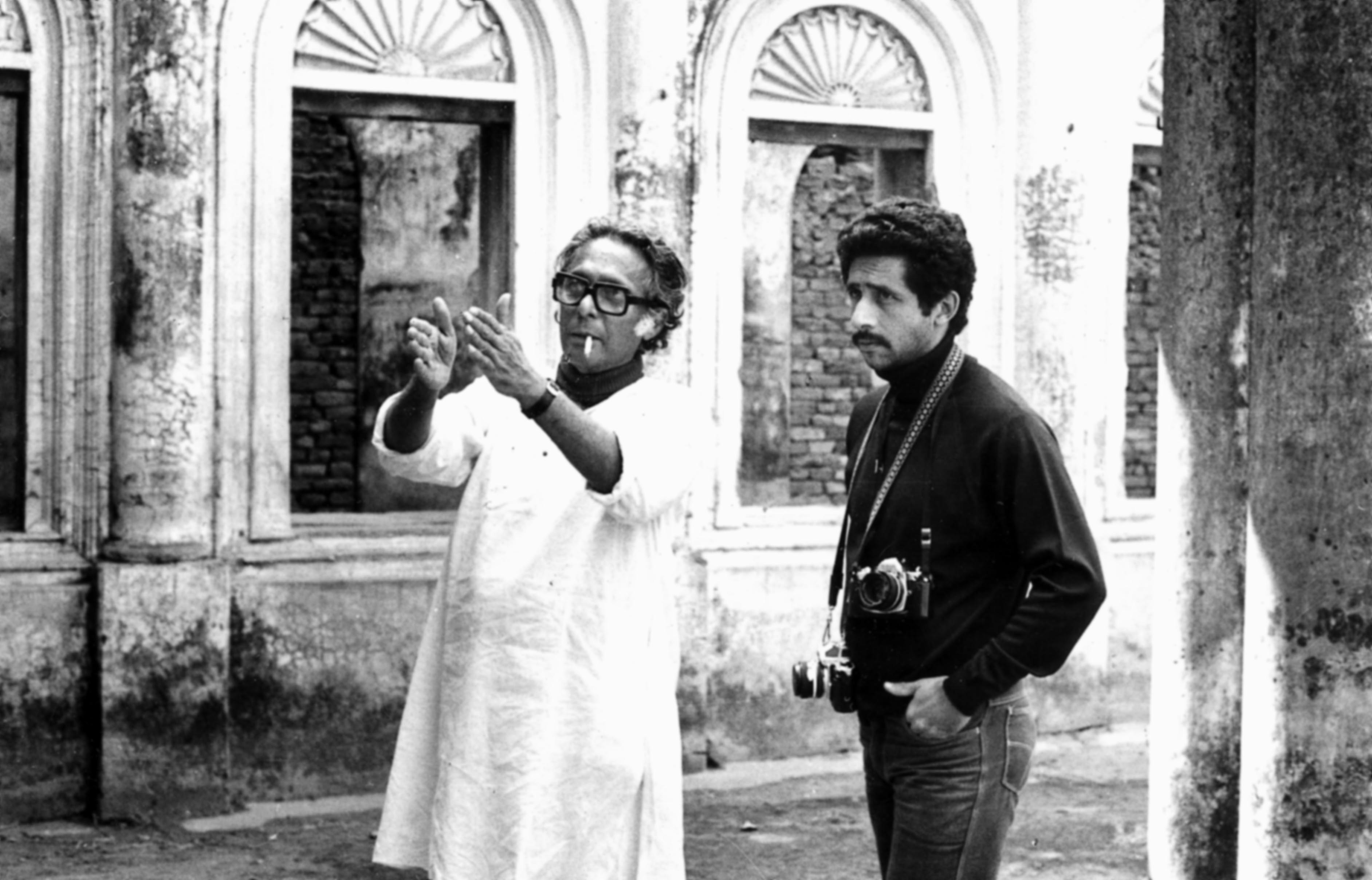

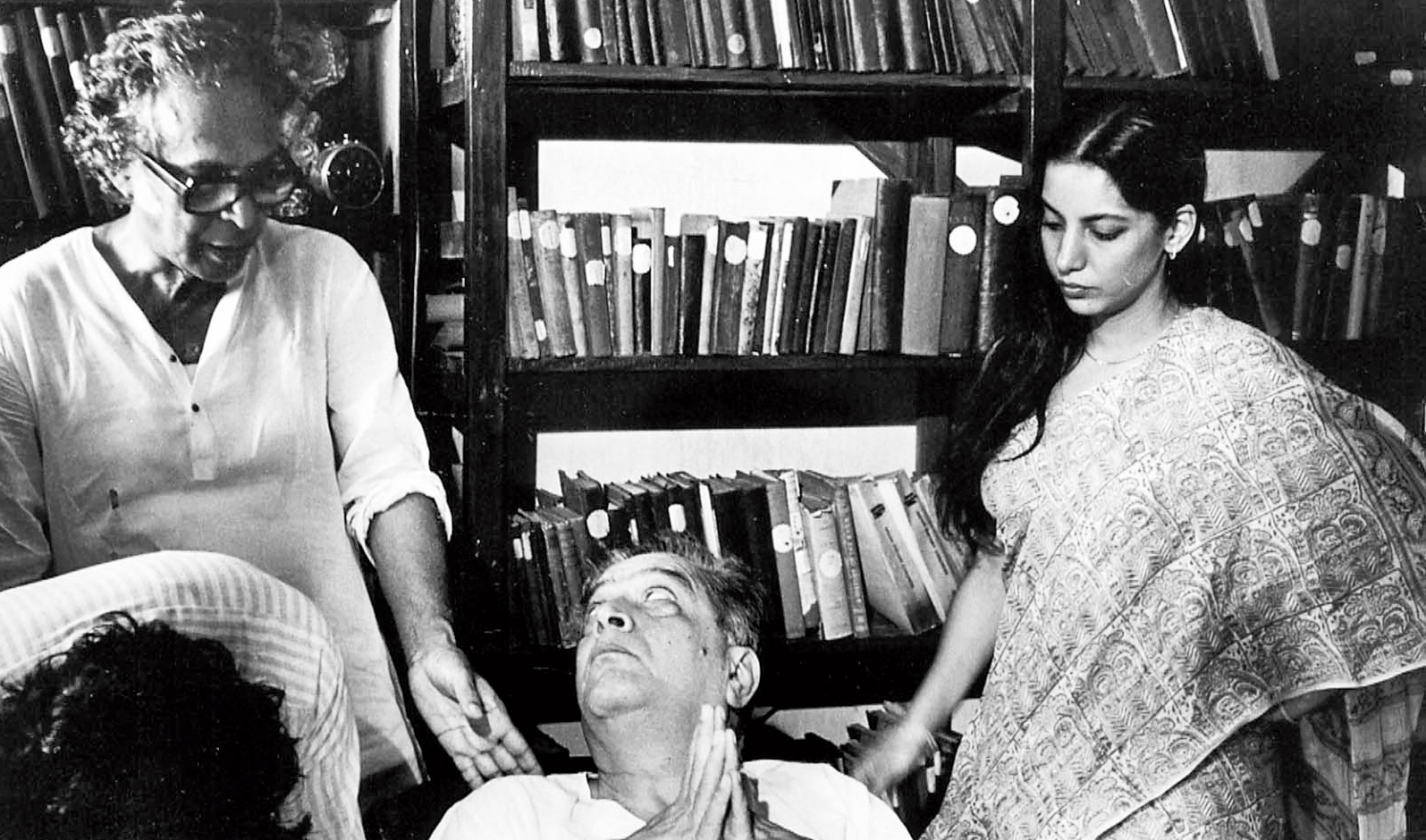

Of the four, Mrinal Sen was the only one I got to know a little bit. I met him in 1982, when he came to visit my father about filming one of his novels. The project never reached fruition but the introduction allowed me to attend a few days of the Khandahar shoot, and after that it was ‘Mrinalda’, always full of stories, their branches hanging heavy with famous international directors’ names, always ribbing me about whichever film I was working on, whether as assistant or directing my own. What I liked about the man was that he completely eschewed what I call the ‘great-man-persona’. Mrinalda was approachable, you could ask questions of him, within limits say critical things about his work, rib him back. If you were a smoker, around him you watched your ignition equipment like a hawk; towards the end of a day’s shoot he would be striding around, his bulging kurta pockets rustling with borrowed matchboxes and lighters while the rest of the unit was going crazy without a light. He wasn’t without ego or a sense of self, but he wore this lightly. Unlike so many other famous, senior practitioners of the arts, he was actually, genuinely curious and interested about the work younger people in his field were doing. He could be extremely serious but he was never very far from laughing at himself, and in this he was rare.

Satyajit Ray is often quoted as having described Ritwik Ghatak as being “the most Bengali of our film-makers”. It is not clear whether Ray was provincializing Ghatak or praising his rootedness, but if Ghatak was the most Bengali then Mrinal Sen was definitely the most international of the four, with his self-deprecation the most open to whatever was going on in world cinema. With Sen you could constantly sense the excitement of someone who was discovering new colours to add to his palette, Italian neo-realism, the New Wave of Truffaut, the New Wave of Godard, then the different political engagements of Gutiérrez Alea, Solanas or Güney, and then the delicately lensed intimacies, the micro-dramas of the great Czechs and Poles. If Ray, centrifugal, pulled the world in to himself, if Ghatak and Tapan Sinha didn’t care one way or the other, then Sen was centripetal, constantly taking his wares — himself and his Bengal — out to trade in the bazaar of cinematic ideas.

This is obviously not the space for discussing the merits and nuances of Mrinal Sen’s work in any detail. What one can do here is to join in the celebration of a long life of hard work well lived, join in the recognition of a career full of ups and downs that was conducted with no little grace and honesty, join in the memory of the camaraderie and laughter that one found on his sets, join in acknowledging a life conducted under the pressure of some fame and accolades yet without any of the usual pomposity and bombast that accompany constant recognition.

As time passes you realize that there is no quarter-final between Bhuvan Shome and Aranyer Din Ratri, no semi-final between Devi and Meghe Dhaka Tara or Jatugriha and Ek Din Pratidin or a three-way play-off between Ashani Sanket, Titash Ekti Nadir Naam and Akaler Shondhane. With the passing of Mrinal Sen you realize that the period, at least between 1955 and 1985, was a special passage of time, one from which future generations will receive from Bengal and Calcutta a layered, four-channelled chorus, a complex cinematic tapestry woven in four distinct threads of black and white and colour. And, having received this, if someone were to make the mistake of removing or reducing any of the different elements it would be their loss and the loss would be great.