Kozhikode, called Calicut by the English, has long been known as the acclaimed spice port where the Portuguese sailor, Vasco da Gama, stepped foot in 1498, opening the five-century-long Western colonial invasion of Asia. But since 2018, Kerala’s third-largest city has been in the news for repeated outbreaks of the Nipah virus, a zoonotic pathogen with a high mortality rate of up to 75% compared to the 2-3% for Covid-19. Kerala has faced Nipah outbreaks four times in five years with three of them in Kozhikode and one (2019) in Ernakulam.

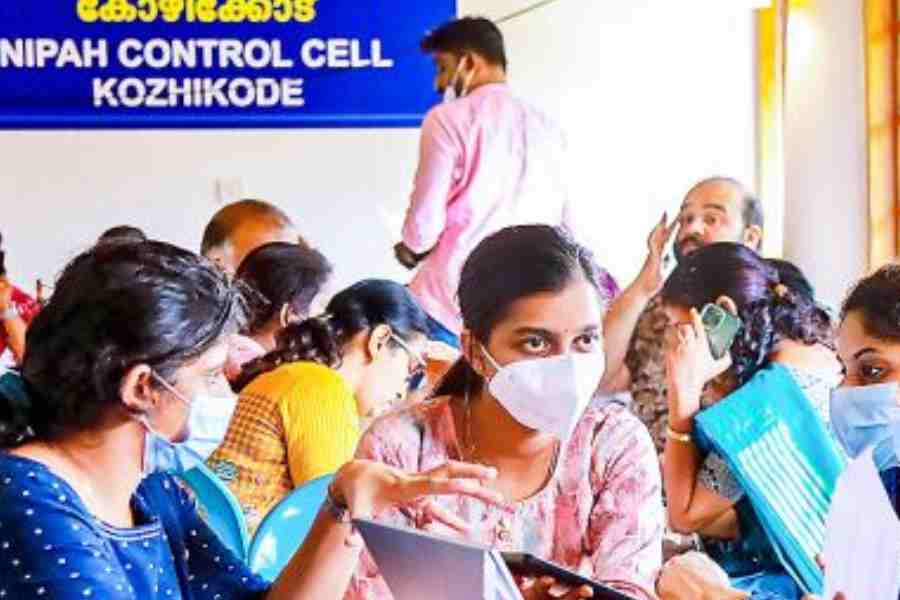

The latest outbreak in Kozhikode in late August killed two men in their forties before the state government declared it contained after a fortnight. With shops and schools immediately shut down, roads deserted and face masks making a return, panic had spread across the state, bringing back dreaded memories of Covid-19. Kerala was the first state in India to report Covid in early 2020.

On September 16, the state government declared the infection contained with no new cases being reported and discounted the chances of a second wave. According to the health minister, Veena George, a total of six persons had tested positive for the virus, with two deaths and four patients under successful treatment with monoclonal antibodies imported from Australia by the Indian Council of Medical Research. Body fluid samples of more than 15 high-risk contacts of the deceased had tested negative for the virus at ICMR’s National Institute of Virology, Pune.

All patients, including the second deceased, had contracted the infection from the first patient (E. Mohammedali, 47) who died on August 30. The second person (M. Haris, 40) died on September 11 and had contact with Mohammedali, whose nine-year-old son and brother-in-law were also infected and treated. The virus was detected after the second death.

The Nipah virus causes highly fatal respiratory and encephalitic infections in humans with fever, headache, muscle pain, convulsions and so on. According to George, the virus strain found in Kozhikode was a deadly Bangladeshi variant. Nipah can be transmitted to humans through primary hosts like bats or intermediaries like pigs. Infection occurs when humans or intermediary animals eat fruits contaminated by bats.

Seventeen people had died when Nipah broke out for the first time in South India in Kozhikode in 2018, presumably transmitted from fruit bats, also known as flying foxes, that carry the virus. The virus hit Kozhikode again in 2021, causing no deaths. In between, a single case was reported in 2019 in the Ernakulam district (200 kilometres south of Kozhikode) with full recovery. In Kozhikode, all three times the infections occurred in the panchayats neighbouring the biologically diverse slopes of the Western Ghats.

Even though the outbreak was contained within a fortnight, many questions remain. Why does only Kerala, known for its impressive public healthcare system as was evidenced during the Covid outbreak, face recurrent viral outbreaks, even though Nipah has been found in nine states and one Union territory? Why does Nipah target Kozhikode frequently when viral circulation has been found in many districts? Another key unanswered question is how was the first patient — index case — infected during each outbreak? Although Nipah-carrying fruit bats (Pteropus medius) have been found in Kozhikode’s affected areas, it is not yet conclusively proven how they infected the first victim. It is only assumed that it was from eating fruits contaminated with bat saliva.

Criticism mounted against the state government, once universally praised for its management of Covid-19, especially during the early stages. Many asked why a comprehensive epidemiological study of the Nipah infection, including bat surveillance, has not yet been done and why an effective preventive mechanism was not in place even five years after the first outbreak. The Opposition blasted the government for its inability to prevent the recurrence and deaths. Critics accused authorities of knee-jerk reactions, waking only after the virus strikes and returning to slumber once the threat recedes. The World Health Organization and ICMR had flagged the entire state’s susceptibility to such infections and stressed the need for precautions.

An ongoing, nationwide ICMR-NIV survey found evidence of the Nipah virus-carrying bat population across nine states and one Union territory. They are Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, Meghalaya and the Union territory of Pondicherry.

The Nipah virus first surfaced in the world in Malaysia in 1998, where it was transmitted to humans through pigs infected by bats that dropped partially eaten fruits near pig stalls in a village on the banks of the Nipah River. The virus got its name from this river and the humans who were infected first were pig breeders. Singapore reported Nipah infections next, again through pigs. In India, Nipah was first reported in 2001 in Siliguri, West Bengal, taking 45 lives. Siliguri’s neighbouring Bangladesh has reported the Nipah outbreak almost annually since 2001, mainly among those who consumed raw date palm sap contaminated by bats. Malaysia and Singapore reported no outbreak since 1999 after Nipah killed 100 persons, prompting the culling of one million pigs.

According to George, various measures and facilities have been implemented in Kozhikode since the first outbreak. This includes a protocol for diagnosis and training of health workers, including senior doctors. After the outbreak was reported in 2021, the ICMR set up a mobile lab at Kozhikode’s Government Medical College. In 2019, the Institute of Advanced Virology was set up by the state government in Thiruvananthapuram with Bio-Safety Level 3 facilities to handle high-risk viruses and is expected to be upgraded to BSL-4. Pune’s ICMR-NIV is Asia’s first institute to have BSL-4 facilities and it has a unit in Alappuzha since 2008. Only ICMR-NIV is legally entitled to declare the incidence of a virus outbreak, says George, in answer to a question about why samples continue to be sent to Pune despite having facilities in the state. George has also announced the setting up of a State Centre for Disease Control with an Interdisciplinary Centre for Epidemic Forecasting and Mitigation, along the lines of the United States of America’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Experts believe that urbanisation and bats’ spillover from nearby forests are the key reasons for the outbreaks. Many also feel that Nipah is being reported recurrently only from Kerala and Kozhikode owing to the state’s better healthcare system, with superior monitoring and diagnosing in place since the first outbreak in 2018. In other states which have the presence of virus-carrying bats, the infection and casualties could be going undetected.

The absence of vaccines has made Nipah even more dreaded. Last year, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the US announced clinical trials for an investigational preventive vaccine for Nipah. The ICMR also has announced starting work to develop a vaccine. However, some observers feel that most major global drug companies do not appear keen on investing on a vaccine for an infection affecting only a few in Asia.

M.G. Radhakrishnan, a senior journalist based in Thiruvananthapuram, has worked with various print and electronic media organisations