July is the perfect month to watch Loving Vincent. Three days from now, on July 27 — but 130 years ago — Vincent van Gogh shot himself in the chest with a Lefaucheux revolver. There were no witnesses to the ‘suicide’, but it is believed that the bullet had been fired either in a wheat field — van Gogh used to paint there — or inside a barn. Vincent died two days later; “The sadness will last forever,” were his last words to his brother and confidante, Theo.

In Loving Vincent, Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, the directors, decide to leave a few splotches of paint on the rather neat canvas of Vincent’s death. There are suggestions that an ugly row between Dr Paul Gachet — Vincent found him “eccentric” — and the artist in which the medical man had accused van Gogh of being a burden on his beloved brother may have led to Vincent pulling the trigger. The needle of suspicion also turns, briefly, towards a local lad who bullied Vincent and was known to possess a firearm. But Loving Vincent, while following each suspicious trail, leaves it to the viewers to draw their conclusions on Vincent’s demise.

Where Kobiela and Welchman are far less ambiguous is in their interest in exploring Vincent’s fascination with stars. Loving Vincent is a stunning example of technological and artistic wizardry: every single frame — 65,000 of them — used in this animated, experimental film is, in fact, an oil painting, put together with care and skill by over 100 artists emulating the techniques used by Vincent. These cinematic frames recreated from Vincent’s artworks form many of the backdrops of scenes, with two significant conversations taking place under starry, starry nights. In the first, Joseph Roulin, van Gogh’s friend and drinking partner in real life, is seen — well — drinking with Armand, his son, outside Café Terrace at Night, the first of the three paintings that comprise van Gogh’s Nocturne series. Loving Vincent ends with another conversation between father and son, this time under a Starry Night over the Rhône. Vincent finished this painting, a sublime portrayal of gaslights shimmering on the Rhône’s royal blue waters, in September 1888, a few days after he had completed Café Terrace at Night.

Vincent’s interest in the depiction of stars and the interest of Kobiela and Welchman in this aspect of van Gogh’s artistic sensibility merit closer scrutiny. A cursory glance at some of the most astonishing, enduring portrayals of the night in Western art at least in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would reveal that artists usually paid scant attention to stars. Claude Joseph Vernet (Night: Seaport by Moonlight), Henry Fuseli (The Nightmare), J.M.W. Turner (Fishermen at Sea), Francisco Goya (The Third of May,1808), Jean-François Millet (Hunting Birds at Night), Henri Rousseau (A Carnival Evening and The Sleeping Gypsy) J.A. Grimshaw (Nightfall on the Thames), among others, focused on a diverse set of elements — clouds, moon, sky, sea, dreams, iridescent torches, even war and revolution — but stars, inevitably, are either absent or appear as an afterthought on their canvas. When they do cast their distant light, such as in Lieve Verschuier’s painting of a night in Rotterdam or in Rousseau’s A Carnival Evening and The Sleeping Gypsy, these specks of light seem to serve — predictably — an ancillary function. A blazing comet mesmerized Verschuier’s artistic eye; while the eye of the viewer is drawn towards man, beast and moon in Rousseau’s creation. Millet’s Starry Night, as the title suggests, is perhaps a rare exception.

The relative obscurity of stars, as opposed to such other celestial beauties as the moon, within the artistic vision of the time is all the more peculiar because of the developments that were taking place in the world of astronomy then. Historia Coelestis Britannica, John Flamsteed’s magnum opus comprising an impressive catalogue of stars, shone brightly in 1725; William Herschel — he discovered Uranus — came up with a catalogue of star clusters in 1781; the discovery of asteroids and spectroscopy followed in the next century. These advances, of course, have to be seen as a continuum; stellar astronomical work had been accomplished by the Ancient ones too. The Babylonians discovered the lunar eclipse; the first whiff of the Heliocentric model came — centuries before Copernicus — from Greece; the Islamic world contributed the first astronomical observatories. Yet, art retained its blind spot.

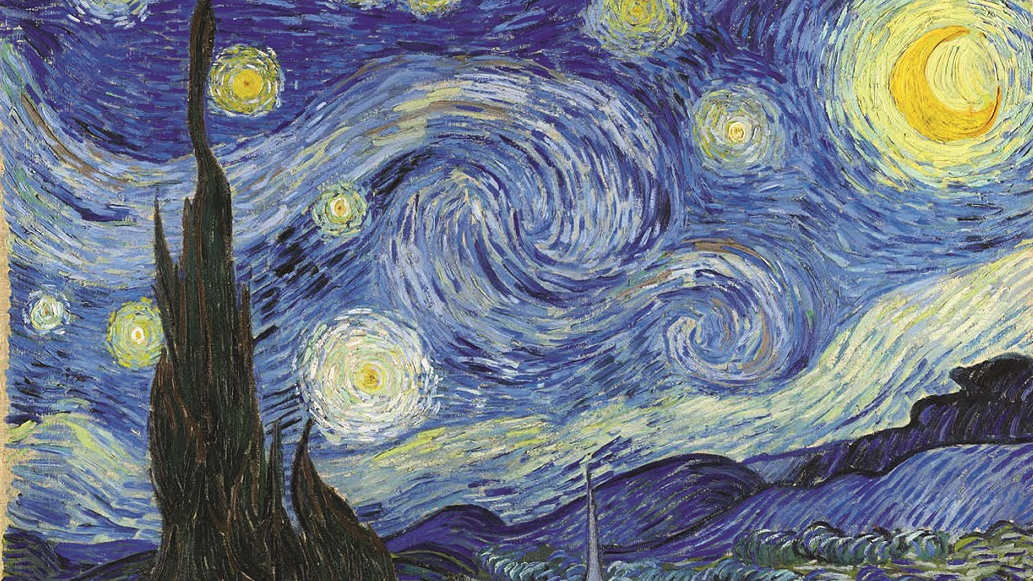

What did our man, Vincent, make of stars? Or of his three paintings with those bejewelled night skies? His letters to his brother, wonderfully edited by Irving Stone in Dear Theo, drop sporadic, cryptic, but profound hints. In an oblique reference to Café Terrace at Night, Vincent confessed to his brother that “… [H]aving a terrible need for — dare I say the word — religion... I go outside at night to paint the stars…” A letter to his sister offers a more detailed, but also prosaic, description: “I was interrupted precisely by the work that a new painting of the outside of a café in the evening has been giving me these past few days. On the terrace, there are little figures of people drinking. A huge yellow lantern lights the terrace, the façade, the pavement, and even projects light over the cobblestones of the street, which takes on a violet-pink tinge. The gables of the houses on a street that leads away under the blue sky studded with stars are dark blue or violet, with a green tree. Now there’s a painting of night without black.” Indeed, colour and luminescence — gaslights were in vogue — are also critical to comprehend Starry Night over the Rhône that van Gogh described in another letter to Theo in which he made his excitement with kindred and contrasting tones quite evident — “The sky is aquamarine, the water is royal blue, the ground is mauve. The town is blue and purple. The gas is yellow and the reflections are russet gold descending down to green-bronze…” He was rather economical about The Starry Night (picture), only alluding to his enchantment with the “morning star” and describing the painting as a “new study of a starry sky” in a pithy note written from Saint-Rémy, a year before his death.

Vincent’s reticence has been compensated somewhat by studies of these very paintings by art historians. Café Terrace at Night, arguably, has undertones of the Last Supper. The hallucinatory forms of the stars in The Starry Night have been attributed to Vincent’s turmoil that was at once mental and spiritual.

Yet, there may well be another explanation for Vincent and his stars. Tormented by a crippling, recurring mental condition, by his seclusion in an asylum, his anonymity as an artist, financial strain as well as physical exhaustion brought about by prolific creativity and always — always — aware of time slipping, Vincent — having turned his gaze away from the cornfields, sunflowers, cypresses, thistles, hills, peasants — may have looked up for deliverance and spotted (and empathized with) a sky full of stars whose light was yet to reach the world of art.