In 1931, the annual meeting of the Indian National Congress was held in the port city of Karachi. Vallabhbhai Patel was elected president. Early in his address, Patel remarked: “You have called a simple farmer to the highest office to which any Indian can aspire. I am conscious that your choice of me as first servant is not so much for what little I might have done, but it is the recognition of the amazing sacrifice made by Gujarat. Out of your generosity you have singled out Gujarat for that honour. But in truth every province did its utmost during… the greatest national awakening that we have known in modern times.”

In 1931, the Congress had been in existence for more than four decades. Yet in this time, it had never before elected a person born in a peasant household to head the organization, this despite Mahatma Gandhi’s own claim — and exhortation — that “India lives in her villages.” All past presidents of the Congress had been city-bred and city-raised.

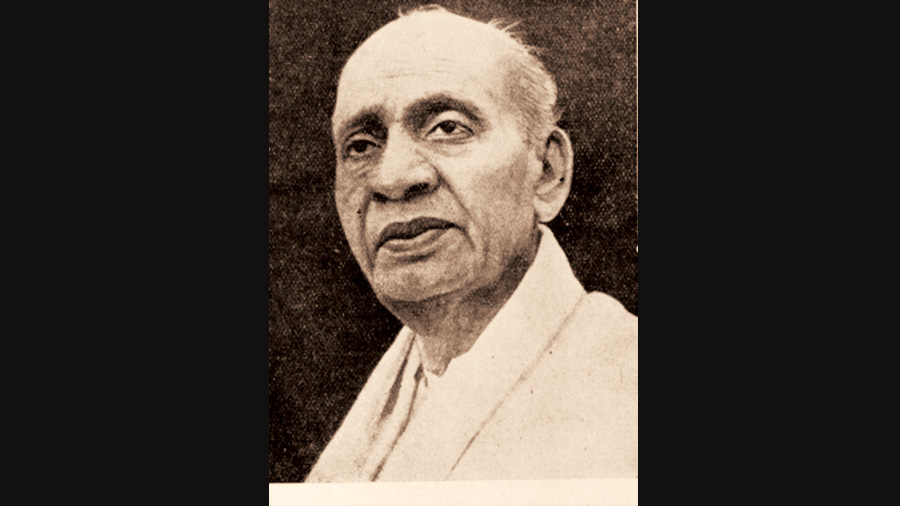

Vallabhbhai Patel was the first major leader of the freedom movement who came from a rural background. Notably, it was as a mobilizer of peasants that he first made his mark on the national stage. Recent discussions of Patel’s historical legacy have stressed his crucial role in the integration of the princely states and in furthering national unity in the aftermath of Independence and Partition. Those contributions were indeed substantial, but it would be a pity if an exclusive attention to them obscures his formative work as a peasant organizer. Indeed, it is Patel as a Sardar (leader) of the kisans who seems most relevant to us today when, for more than a year now, peasants in northern India have sustained a satyagraha against the Narendra Modi government.

The Bardoli Satyagraha of 1928, which was led and organized by Vallabhbhai Patel, emphatically demonstrated the power and potential of non-violence in the cause of peasant self-respect. In this struggle, kisans in rural Gujarat mobilized against the oppressive agrarian policies of the colonial State. Rich details of their movement are contained in the records of the Bombay Presidency, now housed in the Maharashtra State Archives in Mumbai.

Patel’s speeches in Bardoli during the months of the satyagraha make for riveting reading, even in translation. In one, he asked the peasants to show courage and sacrifice: “What are you afraid of?” he said in Gujarati: “Confiscation? You waste thousands after marriage ceremonies, then why worry if the [government] officers take away goods worth Rs. 200 or Rs. 500?” “In this struggle,” said the Sardar to the peasants of Bardoli, “it is better to have five persons who are ready to die instead of having five thousand sheep.” In another speech, Patel sarcastically observed that “the Government has kept a steam-roller to suppress the farmers of Gujarat.” In a third, Patel remarked that “a pro-government newspaper says that Gujarat is suffering from Gandhi fever. Let’s hope that everybody gets such a fever.” A police report commented, with some alarm, that Vallabhbhai was consulting “the leaders of almost every village in the [Bardoli] taluka”.

Supplementing the archival records of the colonial State are the old microfilms of that splendid (but now sadly defunct) newspaper, The Bombay Chronicle. In the last week of April 1928, the Chronicle reported as follows on a kisan sabha: “At a cultivators’ meeting at Varad yesterday night enthusiastic scenes of devotion and worship showered upon Mr. Vallabhbhai Patel were witnessed. Women dressed in Khadi, with garlands of hand-spun yarn and offerings of flowers, cocoanut, red powder and rice were paying their respects and making obeisance in unending chains. Songs composed by pious matrons among women-folk, in some places altered to suit the present occasion, invoking God to bless them in their holy struggle for truth were recited by about five hundred women, which gave a religious turn to the congregation consisting of about 2,500 souls.”

In August, the Chronicle reported on a settlement between the satyagrahis and the State, whereby the government agreed to an enquiry “by a Judicial Officer associated with a Revenue Officer the opinion of the former prevailing in all disputed points”. The State released all satyagrahis from jail and reinstated village headmen who had resigned.

In his book on the Bardoli Satyagraha — published in 1929 — Mahadev Desai writes that Sardar Patel’s “apotheosis of the peasant has a twofold basis — his keen sense of the very high place of the peasant in a true social economy, and his poignant anguish at the very low state to which he has been reduced”. “He is the producer, the others are parasites,” said Patel of the Indian peasant. The satyagraha succeeded in Bardoli, writes Desai, because the Sardar taught his fellow peasants two fundamental lessons — the lesson of fearlessness, and the lesson of unity.

Almost a hundred years separate the peasant struggle that Patel led in Bardoli with the kisan andolan of today. Yet the parallels are hard to miss. On the one side, the role of women in sustaining the movement, and the quiet heroism of the satyagrahis, who have braved winter, summer, monsoon and a pandemic and kept their struggle going. On the other side, the attempt by the State to stall and delay, to divide the movement, and to spread falsehoods about its leaders. Thus, in a note dated July 28, 1928, the Bombay Government claimed that Patel had “kept Gandhi out of the movement … because he does not want it to be controlled by a man who would stick at blood-shed and who would cloud the issue by laying stress on spinning, untouchability and so on.” The report went on to make the staggeringly libellous remark that “Vallabbhai [sic] himself is fond of the bottle and in many ways not unlike Rasputin.”

Back in the 1920s, the collaborators with the raj included Brahmin revenue officials and hired goons brought in from outside Gujarat. Now, in the 2020s, it is the police and the godi media that aid the postcolonial State, the first in suppressing the peasants, the second in distorting their message and defaming their leaders. Indeed, in the range of repressive methods used against the farmers — water cannons, the installation of metal spikes on roads, internet shutdowns, hate-filled propaganda — the Modi-Shah regime has exceeded even the White Man’s raj.

Vallabhbhai Patel’s early biographer, Narhari Parikh, quotes him as telling the peasants: “Remember that you who are prepared to lose your all for the sake of truth must win in the end. Those people who have joined hands with the officers will regret their action.” As a follower of Gandhi, Patel hoped that the force of truth and non-violence would in the end compel the government to see reason. “There will be a satisfactory settlement,” he said in one speech, “only when the Government’s attitude changes. When there is a change of heart, we shall immediately find that bitterness and hostility, which now move the Government to action, have been replaced by sympathy and understanding.” Today’s kisan leaders have been animated by the same spirit of hope, although past experience suggests that sentiments of sympathy and understanding may be even more foreign to this regime than they were to the British.

I shall end this column as I began it, by quoting from Sardar Patel’s Congress Presidential Address of 1931. Here, while speaking of the great national upsurge led by Gandhi, he remarked that “it is a fact beyond challenge that India has given a singular proof to the world that mass non-violence is no longer the idle dream of a visionary or a mere human longing. It is a solid fact capable of infinite possibilities for a humanity which is groaning, for want of faith, beneath the weight of violence of which it has become almost a fetish. The greatest proof that our movement was non-violent lies in the fact that the peasants falsified the fears of our worst sceptics. They were described as very difficult to organise for non-violent action and it is they who stood the test with a bravery and an endurance that was beyond all expectations. Women and children too contributed their great share in the fight. They responded to the call by instinct and played a part which we are too near the event adequately to measure. And I think it would be not at all wrong to give them the bulk of the credit for preservation of non-violence and the consequent success of the movement.”

These words of 1931 make for moving reading in 2021, when, once again, peasants in India have offered dignified and resolute resistance to an unfeeling and possibly uncaring administration.

ramachandraguha@yahoo.in