The Right to Education must be upheld under all circumstances, including emergencies. Education in emergencies has emerged as a field of knowledge that brings together principles and strategies that have worked in helping reach quality education to children in times of disaster. This knowledge is based on decades of work by educators and humanitarian aid workers who have worked through a number of disasters like earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, conflicts and pandemics. The lessons from educational interventions in Kutch after the earthquake of 2001, the tsunami of 2004, and education emergency work during the conflicts in Afghanistan, Somalia and Syria could be useful while thinking about school education during the Covid-19 crisis.

Anganwadis, schools, universities and other educational institutions have been closed in India since March 16. The education of many is going to be disrupted and the school dropout rate would rise. What would India’s response be for education during this emergency? How are the states going to enable children’s right to education? There is much to learn from the education in emergency experience.

Years of conflict had disrupted the education system in Afghanistan. During the Taliban regime, girls were not allowed to attend school. Several NGOs initiated community and homeschooling for girls. Many educated women volunteered to facilitate learning in these home schools. Millions of girls benefited with this intervention. We are not espousing alternative schools, but we are certainly advocating ways of reaching children. NGOs have a vast presence on the ground in India and their volunteers can offer critical support to children during the crisis.

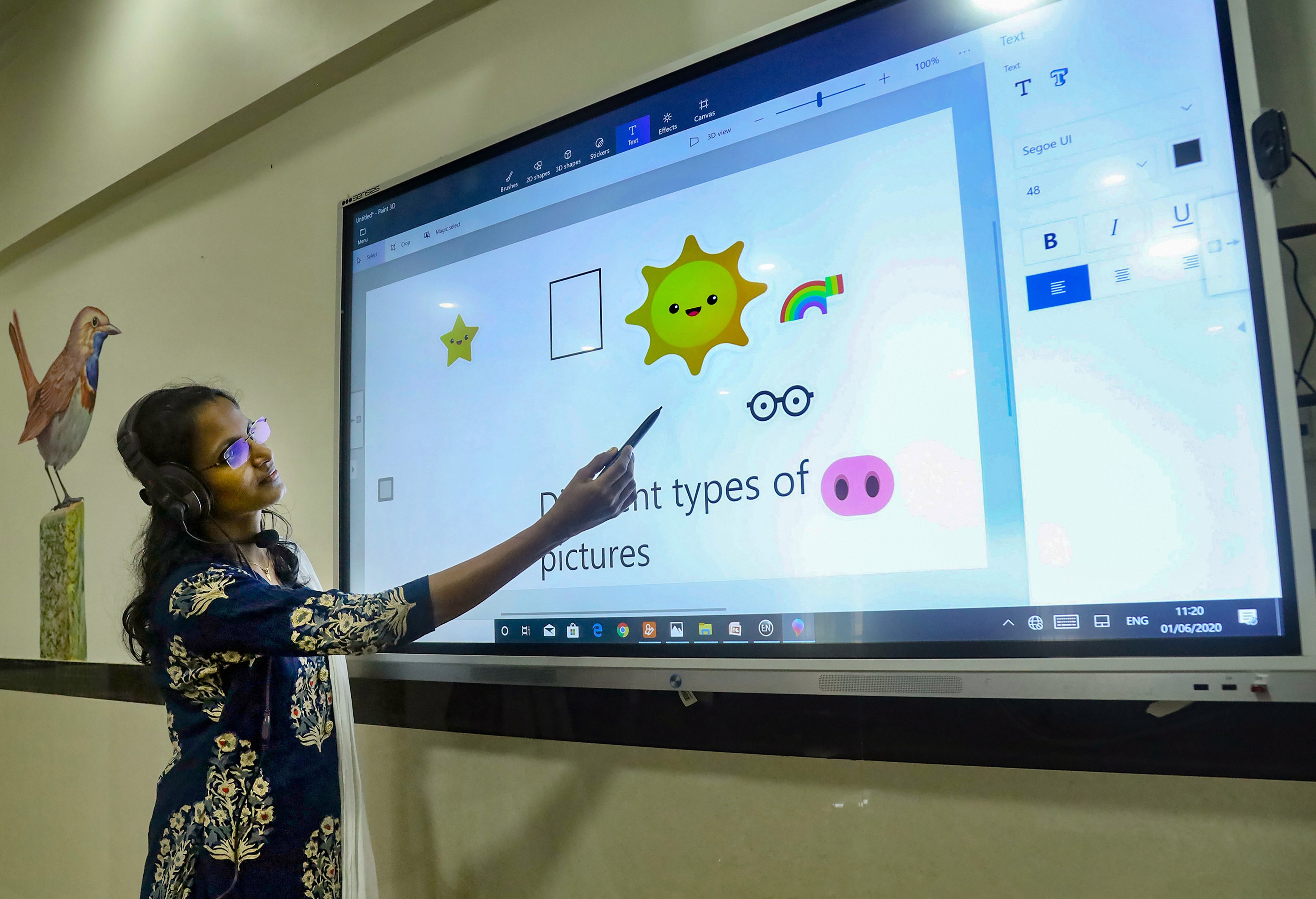

Online education has emerged as an all-encompassing solution. Government agencies and private school managements have joined the bandwagon, with minimal reflection on the challenges. The potential of technology is enormous, but harnessing it requires substantial groundwork. In a country like ours, neither teachers nor textbooks have been prepared to run online classes. Unless the objectives of online learning are made clear, we will not do justice to children’s education.

The disaster that comes closest to the present crisis was the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. The lessons that emerged for education from the Ebola crisis in Liberia were as follows: it makes sense to use communication channels and technologies that teachers and students are familiar with. In Liberia, they made extensive use of the radio; second, the propensity of governments and NGOs to pile children with available learning resources must be tempered so that they are aligned with the curriculum; third, it is important to reach out to and build trust with students, parents and communities; finally, the reopening of schools must adhere to a plan that would look into health and safety issues for children, teachers and other staff.

There are two critical principles that are integral to all the work of education in emergencies: ‘do no harm’ and ‘build back better’. The long-term plan needs to be based on the second tenet. In fact, social distancing could be used to create less congested, clean classrooms and schools.

The ‘do no harm’ principle is critical too. Even well-intended interventions can be damaging. For example, the enthusiasm for online learning could exclude many children who do not have access to computers and the internet. How are we going to make technology inclusive? Social distancing can also be used to discriminate children along the lines of caste and religion.

The Central and state governments need to work with NGOs and other stakeholders to develop short and long-term plans in education in emergency situations that will ensure that learning policy remains well-budgeted and responsive to mitigate risks.