It has to do with the fact that Kamala Harris (b.1964), the vice-president of the United States of America, is fighting for that country’s highest office.

It has to do with that, else the name, Kamala, derived from the Sanskrit for ‘lotus’, which is our national flower, would not be occupying my thoughts as it has been these last few days.

This column is about those whose name is Kamala. Many readers, not some, but many, may groan and exclaim: has the man no sense of priorities? Absurd, they would say, an absurd subject. They would be right, of course. But the human mind is notorious for being just that — absurd. The etymology of ‘absurd’ says it comes from the Latin, absurdus, meaning incongruous, out-of-tune. Being ‘in tune’ is standard. Being out-of-tune, like the celebrated crack in S.D. Burman’s singing voice, can be a not entirely unwelcome change. So, despite several competing ‘issues’ of vital urgency demanding a columnist’s attention, I have let ‘Kamala’ prevail.

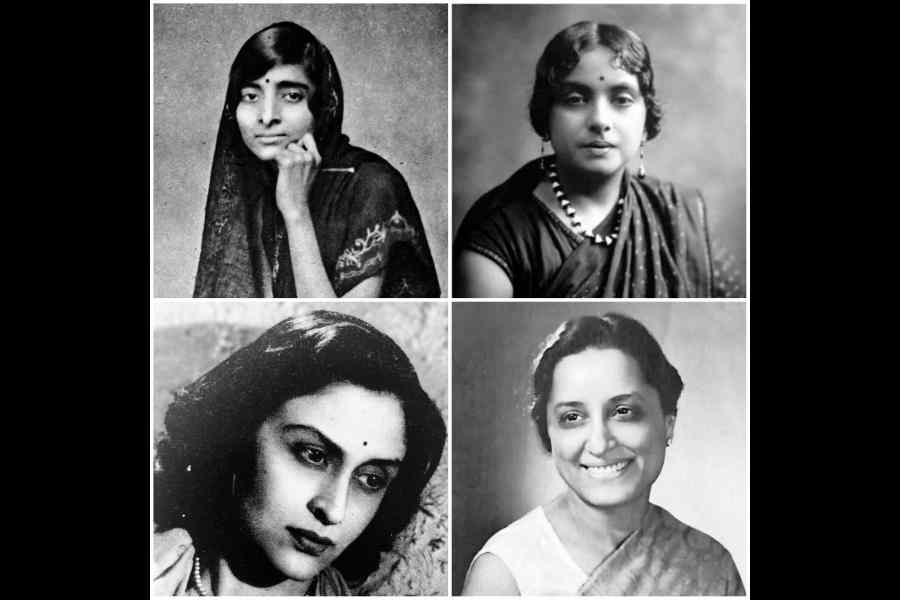

The first Kamala that came to my mind’s recall was Kamala Nehru (1899-1936), immortalised, ironically, by the words in her husband Jawaharlal Nehru’s dedication of his An Autobiography (1936) — “To Kamala who is no more.” The book had been written over many months preceding but published just after Kamala died. Theirs was an uneasy marriage, partly because the Nehru household was very different from the simpler background of the Kauls that she came from. Her closest friend was Prabhavati Narayan (1904-1973), whose own marriage to the revolutionary, Jayaprakash Narayan, cherished as ‘JP’, was not without tensions for the opposite reason. It was he who had to do the difficult adjustments. ‘Adopted’ by Kasturba and Mohandas Gandhi, Prabhavati had been reared in the ashramic tradition of celibacy — no recipe for marital bliss. A sheaf of letters written by Kamala to Prabhavati over the years of their abhinna (inseparable) friendship, was handed over, in his typical trusting generosity, after Prabhavati’s death, by JP to Kamala’s daughter, Indira Gandhi. They are not in the

public domain.

Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay (1903-1988), after whom, we are told, Kamala Harris’s mother named her daughter, was born between Kamala Nehru and Prabhavati Narayan, both of whom she knew well. And apart from being famous as a woman of uncommon intelligence, independence and even insouciance, Kamaladevi was the best MP, cabinet minister, ambassador, governor, vice-president and president India never had. Reason: she did not lobby for those positions and when sounded out for some of them, ‘couldn’t care less’ for the offers. Apart from the best this-and-that she was not, the list of the great things she was included being a dancer, a catalyst for India’s artisanal integrity, a champion of gender justice without any cultivated slatternliness, a socialist without the ism, a Congresswoman apart from the herd. But she too was, like Nehru’s, Harindranath Chattopadhyay’s very differently-wired wife. So different from her husband (who was five years older and lived two years longer) that one hesitates to use the term, ‘wife’, for her.

The third Kamala to come to mind is not just the most beautiful of all Kamalas I have known of or known but, with Rajmata Gayatri Devi of Jaipur, one of the most beautiful women I have beheld. Kamala Markandaya (1924-2004), who would have been 100 this year, wrote a clutch of novels centred on India, from her gentle but not always consoling perch in London. I saw her first in that city when I was eleven and she thirty-two. Her great novel, Nectar in a Sieve, (title drawn from Coleridge’s eponymous poem with the line: “Work without Hope draws nectar in a sieve,/ And Hope without an object cannot live.”) had just come out, making waves. I saw her last, once again, in London, where I was working, when I was fifty-one and she a stunning seventy-two. By this time, another dozen novels by her had been published, all of them of the highest quality but not as successful as her first and she was now almost as silent as she was beautiful. Other novelists and novels had hit the market which had hit new technologies of promotion and marketing. A Silence of Desire (1960) was — is — a high-class work, about, at its core, marriage. A bureaucrat with the very likely name of Dandekar suspects his wife of disloyalty — nothing new! — as she notices her going away quietly on afternoons. But he is soon chastened by the knowledge that a tumour caused her to go on those afternoons to a witchdoctor for cure. By 1994, when she still had ten years ahead of her, Kamala Markandaya said to me she was curtailing her visits to others. A private person always, she was now a recluse. Coleridge’s lines seemed to imbue her inner life.

Another Kamala I cannot forget spelt her name without the middle ‘a’ — Kamla. Her married surname was Chaudhry which, as the scholar of medieval and modern Hindi, Rupert Snell, tells us in his remarkable new book (The Self & The World, Rajkamal, 2024) “has more than twenty variations”. But Kamla Chaudhry (1920-2006) had no ‘variations’; she was singular in every way. Married to a civil servant, she should have had what is the stuff of nuptial blessings — ‘a long and prosperous married life.’ But Khem Chaudhry, as Wikipedia tells us, was murdered one night “as the couple slept” in the north-western province where he was posted. A letter from Tagore, who had known her as a young student at Santiniketan, saved her from despair and she decided to study psychology in the United States of America and work, which is when another singular person, Ahmedabad’s most famous son, the astrophysicist, Vikram Sarabhai, came into Kamla’s life. Giving her a prized and tough responsibility at Ahmedabad Textile Industry’s Research Association, Vikram, who was married to the famous dancer, Mrinalini Sarabhai, embarked on a beautiful and original equation with Kamla. The word for relationships in Hindi is rishta. The novelist, Amrita Pritam, has said famously “rishton ko koyi naam nahin de sakta” (you cannot give relationships a name).

R.K. Laxman, the brilliant cartoonist was married twice, serially, and to a Kamala each time. The first Kamala (b.1924) to be Mrs R.K. Laxman, ‘Baby’ and, later, ‘Kumari’ Kamala the celebrated dancer, turns ninety this year. My generation remembers her with admiration. After his divorce, Laxman married his niece, a writer of children’s books, also a Kamala — a felicity of which one might tell the great man, adapting his pocket cartoon’s title, ‘You Said it — Twice.’

I will round off with a Kamala whom our generation has not seen. Daughter of the polymath, Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, this Kamala (1895-1923) was given in marriage at the age of nine, only to be widowed within a year. Remarkably for those times, Sir Asutosh had Kamala married again at age thirteen only to be widowed yet again within a year. Kamala was herself to die at age twenty-eight. Sir Asutosh’s agony recalls Lear’s indictment of death in Shakespeare’s great tragedy about his daughter, Cordelia.

The story of the great Calcuttan’s daughter has to bring to mind the agony of Abhaya’s parents in Calcutta and Sunil Chatterjee’s heart-churning rendering of Lear’s lines: “Keno ekti kukur-er, ekti ashwar-er, eedur-er-i thakbe jibon, aar tumi… aar tumi... shudhu niswas rohito?”

All names are precious, Kamala among them. I have lingered on it for the persons it evokes in me and their stories which are not just about them but about life.