A distinguishing feature of birth and death is that both elude first-person experience, a possible reason for death’s mystery. However, the reception of death can vary across cultures. For instance, the portrayal of death in Ingmar Bergman’s film, The Seventh Seal (1957), based on his play, Wood Painting (1955), differs significantly from the depiction of death in the tale of Savitri in the epic, the Mahabharata. Further, Sri Aurobindo’s modern rendering of Savitri and other characters in his poem, “Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol”, can be used to highlight the distinguishing feature of women’s engagement with death.

The Seventh Seal’s first conversation, set against the devastation of plague in medieval Sweden, is between Death and the protagonist, Antonius Block, a knight. While returning from the Crusades, the disillusioned knight finds the country devastated by the plague. He challenges Death to play chess, hoping to use the game to delay his demise. Towards the end, Block returns to his castle with his fellow travellers and is received by his wife, Karin. She begins reading from the Book of Revelation about the opening of the Seven Seals by the Lamb. As she finishes reading about the third angel, Death appears. In the last scene, Jof, an actor, reports to his wife, Mia, about seeing Death dancing with Block, Jöns, and the other travellers. But Mia dismisses this as a dream.

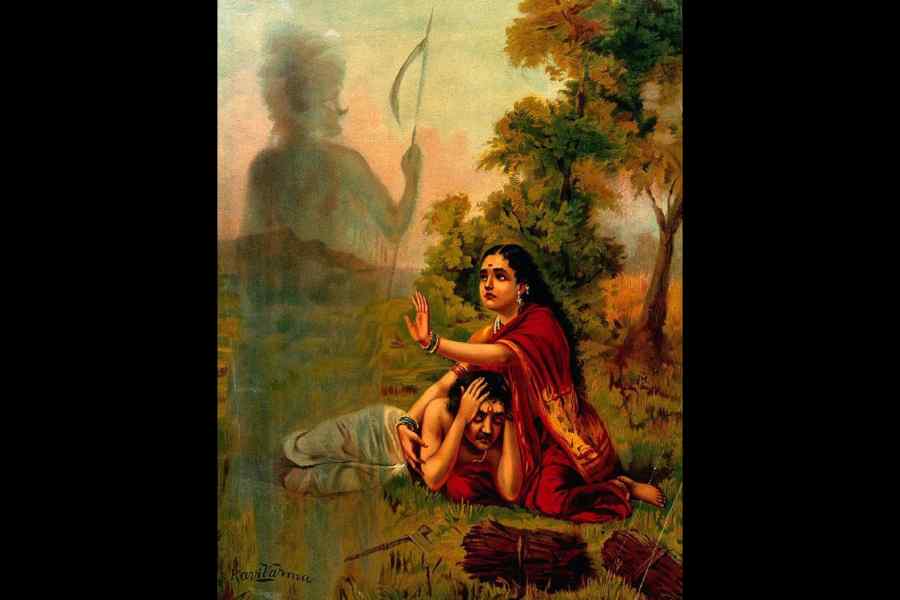

In the film, Death, despite being inescapable, comes disguised as a priest to Block’s confession to surreptitiously and deceitfully find out about the tactics being planned by the knight. Hearing from Block that he uses a combination of the bishop and the knight, Death shows “his face at the grille of the confession booth for a moment but disappears instantly.” Thus, we have Block, the male protagonist and an upright knight, contending with the morally-tainted Death. In contrast, Savitri, a woman, pursues the Lord of Death, Yama Dharmaraja, with persistent requests to bring her dead husband, Satyavan, back to life. Yama does not relent, as this is against the divine norm, the Dharma. However, as compensation, he bestows three boons, anything except the life of Satyavan. For the third and last boon, Savitri asks that she be the mother of a hundred sons. As soon as Yama grants the wish, she reminds him that she cannot bear children without her husband. Yama, being honourable, concedes that Satyavan must be restored to life if the boon is to be fulfilled and grants her request.

Despite the variance in the depiction of Death as victor and vanquished in the film and the epic, a careful reading of both reveals that the film is perhaps closer to reality than Savitri’s story. Sri Aurobindo’s storytelling can be used to make subtle but substantial changes in addressing this difference. He transforms Savitri’s story into a symbol, thus making it universal. Through the symbolic nature of the epic poem, he portrays Satyavan as an embodiment of the “divine truth of being within itself” who has, however, “descended into the grip of death and ignorance”. On the other hand, Savitri “is the Divine Word, daughter of the Sun, goddess of the supreme Truth” who descends upon earth and is “born to save”. Aswapati, her human father, symbolises concentrated spiritual energy that “helps us to rise from the mortal to the immortal planes.” Dyumatsena, the father of Satyavan, is the “Divine Mind here fallen blind, losing its celestial kingdom of vision, and through that loss its kingdom of glory.” Aurobindo concludes that the tale is not merely allegorical; the characters are “emanations of living and conscious Forces”. In his rendering, the fantastical nature of mythology is considerably modified and brought closer to real life, making this story more relatable for readers. In his book, Sri Aurobindo: A biography and a history, K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar discusses some compelling reasons for Aurobindo choosing the theme of Savitri. He mentions that although Aurobindo began writing about Nala and Damayanti, only “about 150 lines have survived.” However, the story of Savitri “gripped” him.

Unlike in The Seventh Seal or mythological stories like Nala and Damayanti, the protagonist in Aurobindo’s epic poem is a woman. But both in the film and the epic, there is an active engagement with Death, whether playing chess or arguing with him. However, in the film, Death cheats to win, whereas, in the story, Yama is the upholder of Dharma, hence the name, Yama Dharmaraja. The uniqueness of Savitri lies not only in being a woman but also in her ability to engage with and win the battle of wits against Death.

Savitri has two distinguishing aspects to her persona. In her hours of deep sorrow, she manages the difficult transition from the emotive to the cognitive level, from grieving to vigorous argumentation, with Yama, which requires a high level of intellectual competency. Two, at one level, her seeking male children as a third boon can smack of promoting patriarchy. However, at another level, she can be seen as central to the lives of two types of men: her husband, who gets his life back because of her, and her male children, who would not have been born without her clever request. There is also another male, Yama, against whom she wins the argument. The combination of woman and death, a unique pairing, remains unparalleled in world literature. Bergman’s film and Aurobindo’s modern epic are discussed to highlight this uniqueness.

A. Raghuramaraju teaches Philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati