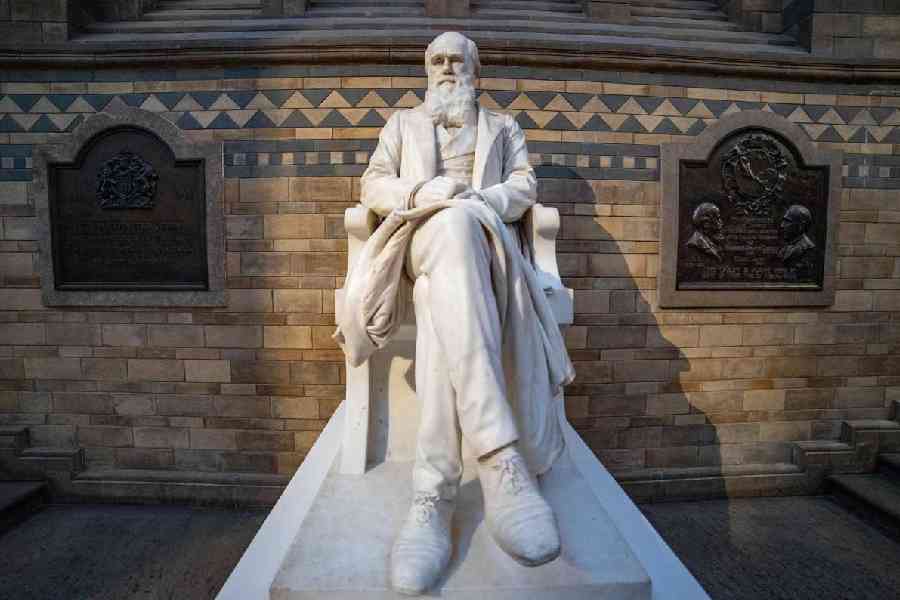

Charles Darwin died a hundred and forty one years ago in April 1882. Of his various publications, two are most well-known. The first is based on a long voyage he undertook on the HMS Beagle as a young naturalist at the age of 22. His diary of 770 pages was published as a journal under the title Journal of Researches into the Geology and Natural History of the Various Countries Visited by H.M.S. Beagle (1839). It created a reputation for him as a cutting-edge naturalist. Although he had almost settled on the theory of evolution by the early 1840s, he kept postponing the publication of his most important work until he noticed that another naturalist was ready to publish a somewhat similar theory. So in 1859, at the age of 50, Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. This was as important a publication in the entire history of science as Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (1687). It changed forever the human perception of the past of animal and plant species as radically as Newton’s treatise did the perception of matter and motion. In his later years, Darwin wrote his autobiography, primarily for his children and grandchildren. Between Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin, they managed to reduce the status of scriptural accounts of the cosmos and life to pure myth and blind belief. Darwin was aware of the wrath of the Church caused by his scientific thesis. Therefore, in the autobiography, he described himself as an “agnostic”. When he died in 1882, the question of his burial came up. To the credit of the Anglican Church, it must be mentioned that the ecclesiastical authorities in England allowed for his burial at Westminster Abbey with full pomp. But the consent for Darwin’s burial did not stop the anti-evolutionary ideas in relation to the past of all species.

In the United States of America, pitched courtroom battles had to be fought to get schools to accept Darwinism. Historically, the most important among these was the case that the schoolteacher, John Scopes, fought when Darwin was banned from the school curriculum in several states in 1925. Orthodoxy remained unmatched in the US over the next four decades, until in the 1960s, when the Supreme Court decided against teaching the mythology of creation as science. However, Darwin’s theory has not had entirely smooth sailing even after the legal success. The year bringing back the memory of the title of Orwell’s dystopia, 1984, saw the publication of The Mystery of Life’s Origin: Reassessing Current Theories, which was co-written by the creationist and chemist, Charles B. Thaxton. Since then, the idea of an ‘intelligent design’ has attracted pseudo-scientists to promote the view that the complexity and diversity of species is far too overwhelming to allow a simple Darwinian formula of evolution and natural selection. This, too, has been argued in the American courts. In 2005, the district judge of Dover, John Jones, ruled that ‘intelligent design’ is merely a religious argument. He reminded the petitioner, Kitzmiller, that the Supreme Court of the US had made it unconstitutional to teach ‘creation science’ (the Biblical myth of genesis) in public schools.

India has now joined the debate. The National Council of Educational Research and Training recently decided to keep Darwin out of Indian school texts. It is surprising that teachers of science in schools and lecturers in science colleges have not tendered resignations in protest. Does it mean that they are no more than mere ‘science labourers’ rather than being scientists? Some courageous scientists protested; but will the government that did not show any sensitivity towards lakhs of farmers who sat on dharna for a year pay heed to protesting scientists? Article 51A of the Constitution has laid down, as a fundamental duty, the fostering of a ‘scientific temper’. But it does not state what scientific temper is. If one were to go by the ‘intelligent design’ thesis, in the Indian context, one has to go back to the Purusha Sukta of the Rig Veda and its ham-handed successor, the Manusmriti. The Purusha Sukta describes the Purusha, the universe (of whom are born the Rig and the Saman — the Vedas), and later the horses and other animals and goats and sheep. The gods divided Purusha. From the mouth of the divided Purusha came the Brahmin; from the arms came the Rajanya; from the thighs came the Vaishya; and from the feet came the Shudra. Such genesis myths mark early literature, particularly the literature that comes to be seen as scriptural, in every civilisation. In the oral literature of tribal communities in India, we come across a variety of such creation myths and stories of the rise of the human species with a certain moral responsibility to keep the universe going. Every religion is based on its unique genesis story, and every culture or nation finds it nourishing to have its own version of how or where it began in some mythical time. Some claim to have emerged from the sun; others claim their origin in the moon; yet others in some distant ocean, or a mythical mountain or forest. What is astounding is that in ancient India, the story of genesis was used as a basis for laws governing inter-community relations. The hierarchy of the vocationally high and the low implied in the Purusha Sukta of the Rig Veda was taken to mean a prescription with legal sanction. Thus any attempt in thought, move or gesture to change the hierarchy came to be seen as a sin against Purusha. Later, at whatever date the Manusmriti came into circulation, Purusha of the Rig Veda was replaced by Brahma, a deity with whom Vedic lore would not have felt at ease.

If this particular myth or other myths prevalent in India regarding the emergence of the cosmos and the species on the earth come to be positioned as the ‘intelligent design’ proposed by India in the remote past, and if these myths are pressed into the vacuum created by shunting Darwinism out of the curriculum, modern India can straight be freed from its Constitution and be delivered to Manusmriti as the ‘Saffron Book’ à la the Red Book in China. Even a cursory reading of B. R. Ambedkar’s Who Were the Shudras? can show how utterly nonsensical the formulation of the Manusmriti was. But leaving aside the question of its implications for the Constitution and its fundamental duties, let us remember that at the last count (since reliable data are on a sabbatical), India had 22,000 science colleges, over 1,000 universities with various science departments and nearly 60,000 doctoral scholars in science streams. If they are required to discard Darwinism as an insult to India’s cultural past, to what great intellectual future is this entirely anti-science government taking them? The NCERT’s dropping of Darwin from the textbooks is, in my opinion, a suicidal aberration without a parallel in modern India’s history.

G.N. Devy is the Obaid Siddiqi Chair Professor, National Centre for Biological Sciences, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research