Nearly 100 years ago, The Register, the first newspaper to have been published from South Australia, had a perceptive subeditor on its rolls. In November 1921, this anonymous desk-hand had given a rather illuminating headline. “Gandhi’s Grief” — the headline — accompanied a news report that talked of M.K. Gandhi’s lamentations about the communal fire that had singed Bombay that year. The choice of the word, ‘grief’, on the part of that subeditor, is revealing. For it fuses the personal with the political unambiguously, corroborating the propensity of the public discourse on Gandhi to fasten the Mahatma’s emotional register to the ebb and flow of the politics of a subjugated nation.

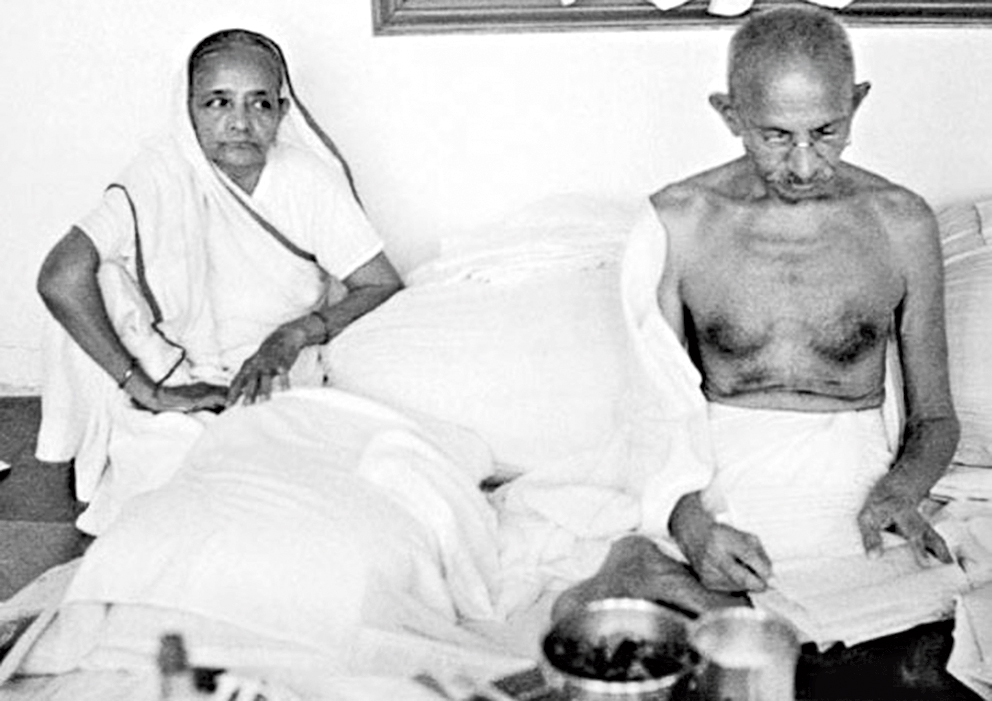

But did Gandhi also grieve in a mundane, altogether human, way? How did he cope with, say, bereavement? February, in fact, is an ideal month to explore Gandhi’s experience of, and confrontations with, grief. Kasturba, his wife of 61 years, died this month in 1944 during her incarceration along with her husband and some others in the aftermath of the Quit India proclamation at Poona’s Aga Khan Palace. Kasturba’s death had been preceded by the passing of Mahadev Desai — Gandhi’s Boswell or, in Kasturba’s words, Bapu’s “right hand and left hand” — by a little over a year.

Several literary accounts of this season of mourning in Gandhi’s life survive. Among these, The Spirit’s Pilgrimage (Madeleine Slade), The Diary of Manu Gandhi: 1943-1944 as well as the diary entries made by Sushila Nayar are particularly instructive, primarily because each of these works is a first-hand account of that time compiled by those who were present on one or both of these solemn occasions. The pull of these works on the researcher is magnetic. Slade, Manu Gandhi and Nayar not only offer rare, rich glimpses into a world that lay inside the gilded prison that was the Aga Khan Palace but their perspectives on similar events also appear to differ quite often, illuminating the chroniclers’ singular contemplations on life and loss. Consider the accounts of Kasturba’s moment of demise in the eyes of Slade. “On the 22nd the last crisis came. Bapu held her in his arms. As the breathing began to change he said to her gently, ‘What is it?’ And she answered in a sweet clear voice, with a tone of wonder in it, as if she were experiencing something totally new and wonderful: ‘I don’t know what it is.’” Manu Gandhi’s observations of what was unfolding in front of her eyes echo Slade’s, save for one perceptible divergence. Gandhi’s grandniece had found Kasturba’s final words “tragic and sad”. Nayar’s diary, Ramachandra Guha writes in Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World, demonstrates an almost clinical tone, bearing assiduous, hourly notes of every single mark of deterioration in that ailing body.

Where such retellings converge, however, is in their depiction of Gandhi’s unequal battle with grief. In a poignant essay on Kasturba’s final days, Devadas wrote this of his father: “He was looking... fagged... But he maintains a philosophic calm... when my brothers and I parted company with the camp... he cracked his customary jokes as a substitute for tears.” Slade, on her part, mentions the daily, sombre rites that took over Gandhi’s life. In spite of Gandhi’s weakened constitution — he had been struck by a bout of malaria soon after Kasturba’s death — he never failed to visit the simple, stone-and-mud memorials of Kasturba and Mahadev. But the most telling register of Gandhi’s sorrow is borne by the following words in Manu Gandhi’s diary: “During the walk... Bapuji said, ‘I am afraid. There is pressure on my mind. I do not know what I would be able to do once outside. I feel no enthusiasm.” The emptiness that Gandhi alludes to could, metaphorically speaking, well have been in the shape of Kasturba.

This absence of equanimity in Gandhi, recorded for posterity by these observant writers, is important, not the least because of its exceptionality: Gandhi’s composure in the face of provocation and adversity was formidable. The capitulation to mourning, however momentary, lays bare our historical and philosophical — civilizational? — failure to come up with effective ways of coping with death and affiliated pain. Death posed an ethical quandary for Plato; he found a way around it — quite problematically for the 21st-century grief counsellor — by proclaiming the fear of, or, for that matter, the grief in, death to be lacking in virtue. Modernity, in turn, has found the Socratic discourse on grief unethical. So much so that neither the State nor technology seems to be indifferent to the plight of the grieving. Two years ago, Britain appointed a minister of loneliness; organizations — charitable or mercenary — offering bereavement counselling are no longer uncommon; earlier this month, The Times reported that Artificial Intelligence, much like the shaman of yore, is now being harnessed to help the living reach out to the departed.

All this could be because grief continues to gnaw at modernity’s sinews. Perhaps a part of the problem lies with the futile, but entirely human, urge to erase the suffering caused by grief. In It’s OK That You’re Not OK — there is no reason to mourn the tawdry title — Megan Devine, a psychotherapist, argues that the cultural inclination to resolve grief must be replaced by a socio-medico-scholarly thrust on viewing grief as a process that requires a continuous engagement.

But the communion with grief can be a terrible burden. Yet — let us return briefly to Gandhi — that man, who had been consumed by grief, had not hesitated to not shield his ‘apprentice’ from it. In May 1947, Gandhi, The Diary of Manu Gandhi informs us, had told Manu, “... [I]f I die taking God’s name with my last breath, it will be a sign that I was what I strove for and claimed to be.” That moment of three bullets piercing Gandhi’s flesh enabled Manu — the assassin had to push her away before taking aim — to testify to the truthfulness of Gandhi’s striving.

Why did Gandhi desire Manu, then only 22 years old, to be a witness to his demise? Perhaps he knew, somehow, that experiencing the loss of the deepest kind is, ironically, the necessary prelude to understanding and, then, enduring grief.

uddalak.mukherjee@abp.in