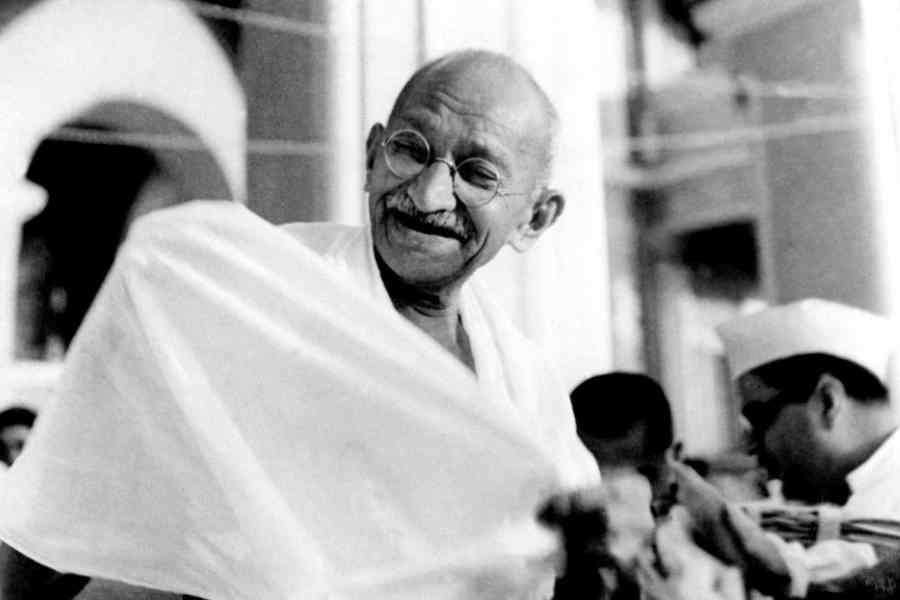

“In true democracy every man and woman is taught to think for himself or herself,” said Mahatma Gandhi. This is the gist of the idea of swaraj, India’s most valuable gift to political philosophy in contemporary times. Swaraj, the core of Gandhian political thought, is centred around the individual-community relationship, the concepts of society, freedom and the State, technological civilisation, and the questions for alternatives. Gandhi had profound faith in the potential of the common man and believed in swaraj as a condition in which the individual would be the complete master of himself.

Gandhi searched for alternatives to existing structures, such as the State, technology, and property. He shared a scepticism for modern civilisation but, instead of harking back to tradition, looked forward to an alternative in which the individual has a vital role. His ideal State was one ruled by selfless individuals. Deeply influenced by Plato’s idealism and concern for moral values, Gandhi preferred the consensus principle that ensured collective welfare over the majority principle.

Gandhi stood for a minimal State that would protect the interests of the common man. Gandhi’s ideal State was one along the lines of Ashoka’s empire, a non-violent and morality-based polity. He loathed the centralisation of power, political and economic. Non-violence was the barometer of progress in Gandhian political dynamics. For Gandhi, the future of civilisation depended on progressive diminution in the use of violence. He pleaded for panchayati raj for realising gram swaraj. In his scheme of things, vyakti swaraj (individual self-rule) is the first step of swaraj, gram swaraj the second, and purna swaraj, the ultimate.

Gandhi’s political philosophy was not utopian: he demonstrated the practical potential of his political ideals. One such instance is the Constitution he helped to design for a princely state called Aundh. On January 21, 1939, the princely state of Aundh (now in Maharashtra) became a village republic based on Gandhi’s ideals, adopting his Swaraj Constitution.

The ‘Aundh experiment’ was a unique occurrence in which an Indian monarch abdicated his throne to allow for people’s self-rule. Gandhi proposed a three-tier government, with each village having a panchayat of five members who would elect a president. The panchayat presidents would elect four taluk presidents and send 12 representatives to the legislative assembly, which would select the state’s prime minister. The Constitution gave every citizen of Aundh a wide array of fundamental rights.

Saadat Hasan Manto’s character, Ustad Mangu, (in the short story, “Naya Kanoon”) is a typical Gandhian common man. A tongawallah, he was a man of wisdom and common sense. One day, Mangu picked up two fares and gathered from their conversation that there was going to be a new Constitution for India. The new Constitution signified something bright for him. But on the first day of the new Constitution, Mangu had a bitter encounter with an Englishman. He was taken by police constables to the station. Along the way, Mangu screamed: “There is a new Constitution now, friends, a new Constitution!” But the policemen locked him up saying: “What rubbish are you talking about? It’s the same old Constitution!”

When our founding fathers framed a new Constitution, they lavishly borrowed from the Government of India Act of 1935: 150 out of 239 Articles of the first draft of the Constitution were copied from the Government of India Act of 1935. The aspirations of Ustad Mangu, the Gandhian common man, regarding the new Constitution have not yet been met. As long as Ustad Mangu remains behind bars, the Constitution would be merely an ineffectual angel.