This winter in Goa, from November 21 till January 5, 2025, sees the once-in-a-decade exposition of the relics of Saint Francis Xavier. This is an opportunity for the faithful to see the ‘incorruptible’ remains of this 16th-century missionary and priest. ‘Incorruptible’ here refers to the quality which devout Catholics believe preserves the bodies of saints.

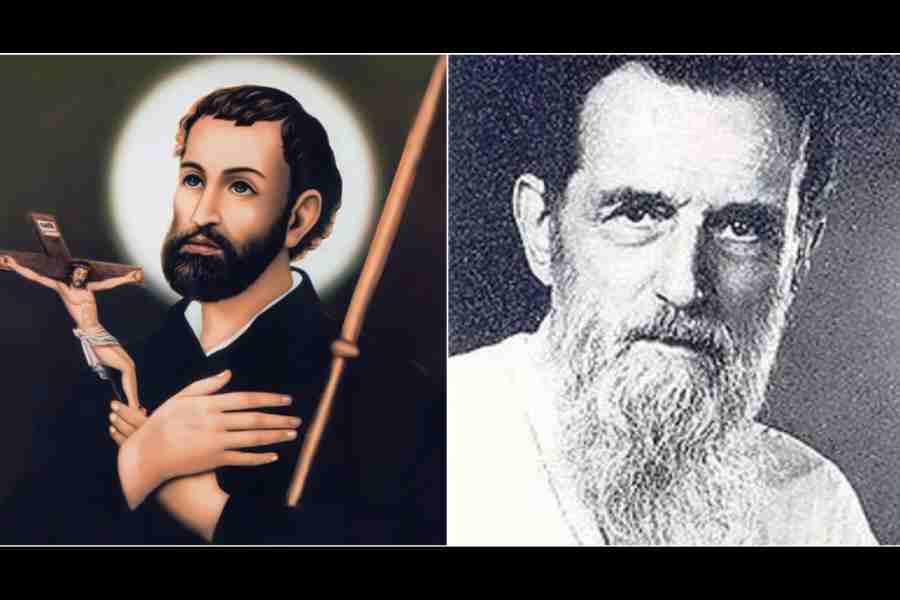

Francis Xavier (1506-1552) was canonised in 1622. He had arrived in Goa in 1542 but travelled extensively in Southeast Asia — as far as Japan and the coast of China. He died on Shangchuan Island off the coast of China and was first buried in Portuguese Malacca in present-day Malaysia before being brought to Goa.

The first exposition took place after his canonisation in 1622 and, thereafter, with greater frequency from the late 18th century. The current exposition is the 18th — the tradition of regular decennial expositions dating from the 1970s, well after Goa’s liberation from Portuguese rule in 1961.

In the decade that St Francis spent in Asia as a missionary, perhaps over half of that time was spent outside Goa travelling and preaching. Yet his identification with Goa has remained strong and many regard him as its patron saint. The India connection is also strong, demonstrated by the vast network of schools, colleges and professional institutions across the country bearing his name. St Xavier’s colleges and schools are also found in a number of other countries.

The experience of the exposition is both spiritual and well-organised. The vast majority are Catholics from Goa and across the country, but there is also a sprinkling of Christians of other denominations as also people from other religions. Multiple masses are held through the day. That these are principally in Konkani underline how much St Francis has been localised and vernacularised to his adherents.

But his life and legacy are also a matter of controversy and, to an extent, these have acquired greater prominence in recent years as polarisations have intensified and in multiple directions. One recent controversy followed a local politician demanding a DNA test since he claimed that the relics were not of St Francis but of a Buddhist monk. In our algorithm-dominated times, this too may appear to have traction but it is possibly no more than the outcome of local political competition.

More significant has been the view that St Francis is a symbol of the Inquisition in Goa and cannot be separated from its worst excesses, including of temple destructions, religious discrimination, and forcible conversions of Hindus to Christianity. Missionary activity was, it is argued with conviction by many, an integral part of the colonial project in India; so why not call it out for what it was and identify the protagonists who caused distress to so many during the duration of the Inquisition from 1560 to 1812?

The Inquisition had emerged in Portugal and, then, travelled to its colonies, including Goa. What lay at its core was the anxiety that Catholics, particularly recent converts to Christianity, were not steadfast in their faith and practice and, therefore, transgressions had to be rooted out. In current terminology, we could explain it as being a kind of extreme moral and religious policing with frequently fatal consequences for those believed to be transgressors and the creation of a pervasive atmosphere of fear and insecurity.

Discussions about the Inquisition in Goa usually veer quickly to Anant Priolkar’s book with that very title. Priolkar was a prominent intellectual (1895-1973) of his time and in his deeply-researched work he shows the Inquisition at its height was responsible for injustice and repression in Goa. He remained conscious, however, that any Indian (and, possibly, non-Christian) who narrates its history could “be accused of being inspired by ulterior motives”. In his view though, “the truth has to be told.”

Priolkar’s book had appeared in 1961 — the year of Goa’s liberation from Portuguese colonialism — and it had an obvious nationalist context. The debate about the Inquisition and its many inequities rages on in Goa in the context of St Francis’s exposition. The polarity Priolkar drew between the truth and ulterior motives remains valid today — perhaps to an even greater extent — for it in undeniable that the apparent quest for historical truth is often a masquerade for ingrained prejudice.

However, there are more fundamental methodological issues involved in passing judgement on past history. Should we judge past actors — St Francis Xavier, for instance — by the standards of our times and in terms of our values or his? In the evaluation of his legacy, are the generations of faith and service that he has inspired more important and relevant, as many claim, than the imperfections of the past?

While reflecting on these issues, I serendipitously encountered a biography of the Catholic priest, Camille Bulcke (1909-1982), by two Sweden-based researchers, Ravi Dutt Bajpai and Swati Parashar. Bulcke lived the vast bulk of his life amongst the tribals of Chota Nagpur and what perhaps characterised his life was not so much missionary activity but rather devotion to Hindi literature and, in particular, to the great Tulsidas while remaining a devout Christian.

Honoured with the Padma Bhushan in his lifetime, Bulcke’s legacy comes to life in an extraordinary development three decades after his death in Delhi in 1982. In 2018, his remains were shifted from Delhi to Ranchi where he had lived for most of his life and buried in the grounds of St Xavier’s College. Amongst Catholics, exhumation and reburial are common in the case of those who are to be canonised. In Bulcke’s case, the reburial was more in terms of a tribal tradition that the remains of elders are carried with the tribe as it moves. It was a fitting tribute to someone who had lived his life with integrity according to the faith as he saw it in much the same way as the exposition of St Francis Xavier’s relics honour his life and, even more, the generations of faith that it has inspired.

T.C.A. Raghavan is a former Indian High Commissioner to Singapore and Pakistan