There is global recognition that humans are deep in an unprecedented catastrophe. The glaring economic inequality and the concentration of wealth in the hands of a very few, ecological devastation and climate uncertainty, the collapse of public institutions within nations and of international regulators in the multinational context, the weakening of democracy and pervasive State surveillance, the arrival of Artificial Intelligence in all private spheres of life, a chasm among religions, cultures and ethnicity, and so many violent and mindless wars make our present world a bleak spectacle. One likes to hope that we have not hit a path of no return; but all that surrounds us points to the futility of such a hope.

Surrounded by such a depressing scene, one likes to turn back and reflect on where it all began. Depending on where one sits in Indian politics, one likes to point to the errors committed by governments and political parties since Independence. Arguments, for and against, can be presented whether India should have first thought of social freedom before seeking political freedom; whether India should have accepted freedom with Partition or turned it down in order to remain a united colony; whether we should have accepted the mixed economy, gone entirely with public-sector ownership of production, or adopted private enterprise from the word go; whether we should have thought of making the country monolingual or made either Hindi or English a national language; whether we should have allowed religion to lead the State or banished religion completely out of the public sphere. These debates, much as they may provide fodder for the rise of a political party or bring down its electoral fortunes, are essentially debates within a narrow band of concerns. A much larger and a more necessary debate is whether the major fault lines of today emerged after Independence, or during the colonial times because of the divide and rule policy of the British, or are they the result of a long period of cultural and political failures during the medieval centuries. In the Indian context, it has been a widespread practice to turn back and point to the medieval era of history as a kind of a dark age, which came after a golden era in ancient times. There is nothing by way of fact which bears out such a view. The contrary is perhaps true; that is the medieval times make us who we are. Why is this so?

The number of feudal dynasties that ruled India during the second millennium were far too many and the division of the territories which now constitute India was far too abrupt to allow us to think of them under a single, generic caption. Yet something that held the Indians in mind and spirit together was a phenomenon called Bhakti. It was a large-scale tradition of social reform, cultural resistance, spiritual rejuvenation, literary expression and local and linguistic resistance to the varna-ashram hierarchy and the religious dogma of the preceding millennium. Although it had its origin in the first millennium, it became more vigorous in the second millennium, peaking in the fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries, continued to manifest itself well into the nineteenth century, and had its impact on twentieth-century life as well. The term, ‘Bhakti’, is in use in most Indian languages. The Tamil variation is Pakti or Pakte. It is often translated into English as ‘devotion’, though devotion is not the same as Bhakti. Devotion brings to mind the idea of a ‘vow’ and ‘loyalty’, while Bhakti invokes selfless surrender or immersion resulting in joy. Etymologically speaking, it emerged out of ‘bhaj’ meaning ‘apportioning’ or ‘participating’. In the context of the history of literature, Bhakti is used as a generic tag for a long era spanning several centuries, many languages, numerous literary forms and hundreds of major and minor poets. In that sense, Bhakti can be compared with literary terms like ‘romantic’ or ‘modern’. It was a social movement of great consequence. It emerged as a challenge to the established social hierarchy, linguistic hegemony as well as metaphysics. As a literary period, and a philosophical and social movement, Bhakti impacted the everyday life of Indians in a way that has no parallel in the entire history of the subcontinent. The manifestation of Bhakti may have differed in different geographical regions in India but its appeal and its impact have been widely felt and internalised by communities across India.

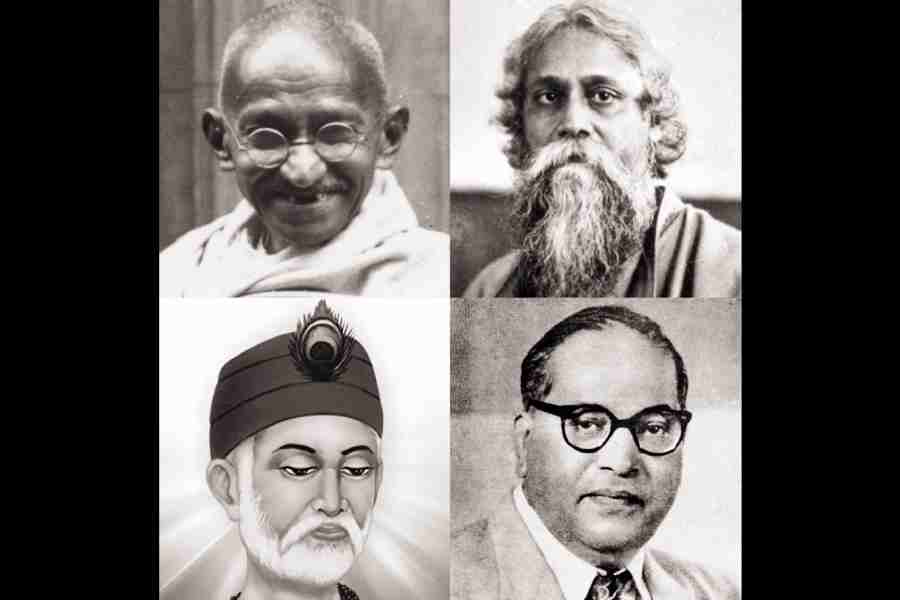

I like to think of Rabindranath Tagore as the last of the millennium-long line of the Bhakti poets. M.K. Gandhi was no poet, though his embattled life can easily inspire an epic. I tend to think of him as the last of the Bhakti saints. The weaver, Kabir, and the spinner, Gandhi, though centuries apart from one another, appear to me as close soulmates. As do the poet-singer, Kabir, and the poet-singer, Gurudev. Sri Aurobindo was both a poet and a saint. I think of him as the one who tried to bring the Bhakti tradition of rebellious spirituality together with the Anglo-European literature he had imbibed in his youth. I also tend to think of Mahatma Phule and B.R. Ambedkar as being part of the tradition of the medieval Bhakti saints who had the courage to challenge the social and metaphysical orthodoxy which had eroded India’s creativity during the preceding millennium. Even though literary scholars consider the Bhakti period as having come to a close by the end of the 18th century, one cannot miss its vital links and continuity well unto the generation of Tagore, Gandhi, Aurobindo and Ambedkar. The Bhakti era spanned a period over a millennium and its spread was all over the areas that now constitute India. It was the making of India during the Bhakti period which helped Indian culture and society not only face and survive colonialism but also draw from it some progressive impulses that were changing contemporary Europe. The Bhakti cultural background, the progressive ideas of Europe which reached India despite colonialism, and the unique freedom struggle got blended and was articulated through the values upon which rests free India’s Constitution. To that extent, in many ways, the medieval Bhakti tradition made modern India what it is. It is another thing that some contemporary schools of political ideology consider this period of Indian history as an era of darkness.

There is no doubt that the Bhakti era was the most momentous in the social history of India. It was a great civilisation era, packed with glory as well as contradictions. The emergence of Bhakti as apostasy — its debates with orthodoxy — and the resulting ecstasy — its enthralling poetic expression — leading to a new vision of life became a significant sub-stratum of India’s selfhood. In the bleak times in which we live, one notices young minds being forced towards imagining the ancient times as a golden era, the medieval centuries as an era of defeat and darkness, the colonial period as a time of complete denial of the self, and the current times as the inauguration of a new, proud civilisation. The more truthful view historically is the one that we are, together with the rest of the world, in the middle of a catastrophe and we need to recover Mira’s love, Kabir’s compassion, Gandhi’s remorse, Ambedkar’s spirit of rebellion and the scientific spirit of the modern West in order to retain ourselves as one among many — very similar — nations and not be deluded by a manufactured pride. The legacy of Bhakti and not the euphoria of the self-attested bhakts will light up the future of India.

G.N. Devy is a cultural activist