It feels odd to lose James Bond and George Smiley within six weeks of one another. It’s true that Sean Connery had last played Bond nearly 40 years ago, and actually left the classic 007 behind much earlier. Likewise, David Cornwell/John le Carré’s oeuvre consists of a lot more than just the Smiley novels — he had finished the quintessential ones by 1979, again just over 40 years ago. However, Bond was what made Connery a household name and many would say the Smiley novels were the pinnacle of le Carré’s output. The realization hits that the passing of Connery and Cornwell in quick succession signals for people like me the end of a schizophrenic, stereophonic era, a termination of a bifurcated, twinned, double helix of a narrative that spins out over 60 years.

I first came across James Bond in the late 60s, in a comic strip serialized in a Gujarati newspaper from Bombay. My parents subscribed to the daily which would arrive in Calcutta irregularly, sometimes nothing for days and then three papers at once, brought back by my father from his office in Barabazar. Not good with either English or Gujarati text, I would wait eagerly till my father unfurled the paper and showed me the four black-and-white panels on one of the back pages. The story was called Moonraker, and one gripping scene I remember going on for weeks was of Bond and a beautiful woman in his convertible Bentley being chased down a highway at night by the German villain, Hugo Drax, in his villainously German Mercedes. There was my father’s voice, reading the English bubbles and then the Gujarati translation given below, and there were the anxiety-making headlights fencing in the black, letterpress night.

After a while I began to pick up English via Enid Blyton, and I promptly used it to decipher the scattered writing in the James Bond photo-magazine I’d picked up from the bookstall on Rashbehari Avenue. On the train to Bombay, two young women hesitantly pointed out to my mother that all those photos of women in bikinis and coming out of the bath and being handed a towel by Connery/Bond were perhaps not appropriate for an eight-year-old. My mother was unmoved. “He’ll understand what he does, but he’s mainly interested in the fighting photos.” I wasn’t incurious about the semi-naked women but my mother was right, my main focus was on the fights, the Aston Martin with the side-spikes on the wheels and the SPECTRE conclaves with the button-triggered seats that could eject you into the shark-pool just below the conference room. Much later I realized it was no coincidence that the Bond in the comic-strip looked just like the Bond/Connery in the photos.

For a few years I was immersed in narratives that installed establishment-loyal Brits and Americans in a good-guy continuum from the Second World War onwards, with Germans, Russians, Chinese and various swarthies hailing from the Mediterranean, South America and Africa interchangeable as the baddies. But as the reading expanded, those assumptions frayed and then atomized. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold was one of the explosive torpedoes that holed the heavy cruiser of English-American fictional self-valorization. Reading it as a teenager, there was a shock of recognition that le Carré could not have intended: suddenly the Brit spymasters were as slimy and treacherous as those of my teachers I wanted to send down as shark-feed into Ernst Blofeld’s termination pool; the Americans were as bad, plus Yank-uncouth; the Soviets and the Germans remained evil but suddenly assumed three dimensions and nuanced colours; in the le Carré books there were equivalents of characters whom I had till then thought of as wholly desi, the bent cops, the sleazy politicians, the small-eyed, unscrupulous babus, the morals-mukt businessmen.

Partly through the early novels of Len Deighton I’d already learned to recognize some of these characters as universal and to laugh at them. Through le Carré’s books they assumed their full rakshasik form, but with human frailties and foibles which the reader also had no choice but to acknowledge. Even if I didn’t then quite understand the hard-wired racism of Ian Fleming, nor recognize the constant, cheerful misogyny of the Bond books and films, the grimness of le Carré’s world connected to India, to Bengal, to bureaucratic file-swamps, and ugly and often meaningless blood-letting.

At a basic level, meta-Bond, the novels, the films, the spin-offs and the merch, the spoofs, all of it is a project of denial of the evil of Empire as well as the disintegration of that Empire. With Bond the Empire is shape-shifted into visiting a newer version of the old ‘noble violence’ on deserving enemies, mollusced on to the American Imperium to maintain a morally laudable hegemony. Le Carré’s work is the direct and pitilessly detailed repudiation of these obfuscations and lie-powered fantasies.

It is no surprise that the more spectacular, superficial super-spy gave rise to a myriad similar narratives in books, comics, films and computer games, even as the Bond movie franchise continues to put out new films under the ‘brand’, making billions of dollars in profit. Today, more than half a century later, you can see traces of that first James Bond of Casino Royale, ‘cruelly good-looking’ in his dandy clothes, in all sorts of movies from Indian counter-jihad sagas to Hollywood’s effects-bloated superhero productions. More importantly, what has inserted itself into the psyche all over the world is the idea of an amoral protagonist, with or without Bond’s expensive tastes and turbo-charged libido, freely utilizing, often relishing, his or her ‘licence to kill’ in the service of country or cause. Today you can find that Bond DNA in characters Irish or Iranian, Japanese or Jat; what identifies them with their mid-20th century progenitor is the gratification delivered by their usually solo authorship of bomb blasts, blood and gore, violent deaths.

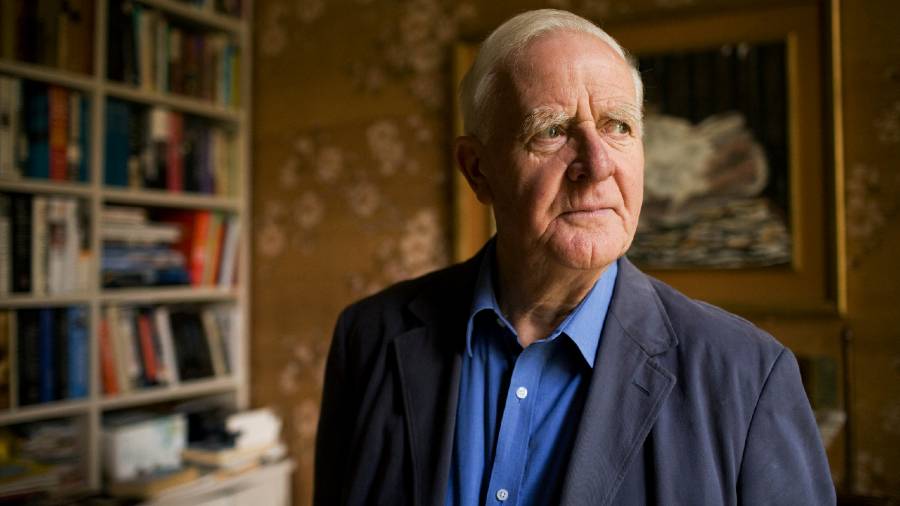

The influence of le Carré and his Smiley and his Circus is perhaps more subterranean, and you are more likely to find it in storytelling that aims at some complexity and depicting moral ambiguity, but the effect is nevertheless widespread. Many of us writing fiction in South Asia have no choice but to acknowledge the debt we owe to John le Carré. I can cite many different examples from sub-continental novels of the last twenty-odd years, but my favourite moment comes from Mohammed Hanif’s A Case of Exploding Mangoes, when the ISI officer picks up the protagonist-suspect for ‘a chat’. As they drive off into the night to what could be a fatally terminal interrogation, the officer points to the cassettes of music under the dashboard and courteously asks: “Asha or Lata?”

The car is probably Japanese, the dangerous man Pakistani, the music, naturally, from Bombay. The old Cold War narratives may or may not be losing their topical relevance. New narratives have certainly taken over, bringing their own peculiarly gift-wrapped anxieties. A lot of what we face today was unimaginable when Sean Connery gave his first shot for Dr. No or John le Carré wrote the first sentences describing Alec Leamas waiting at a checkpoint for an agent to come across the Berlin Wall. A lot has changed,

the future is still dark, but the play of ominous headlights stays constant.