The kiss is not a manoeuvre of endearment alone. It can proverbially also be a prelude to death. You might recall Baazigar, the 1993 movie that triggered Shah Rukh Khan to stardom and was an unvarnished riff on the Matt Dillon starrer, A Kiss Before Dying. Diabolical things can happen around the act of kissing.

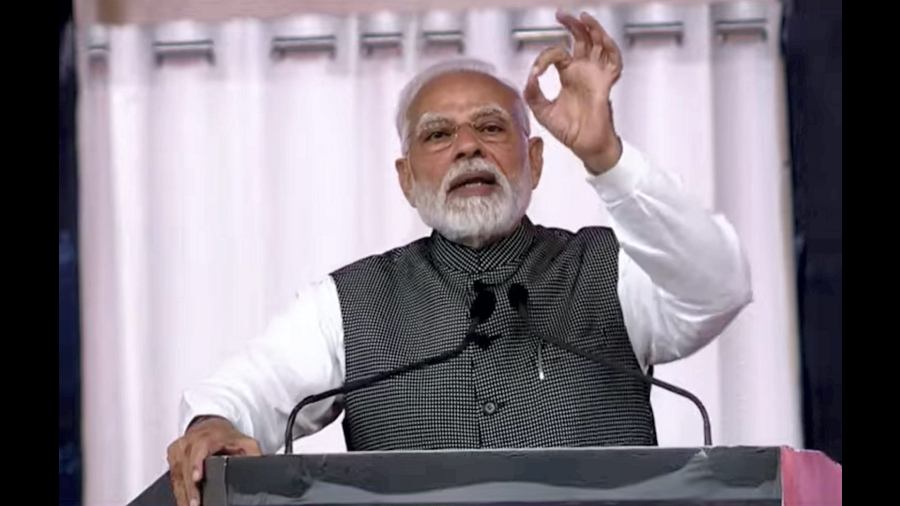

Cut to a more contemporary choreography of kissing. You might recall Narendra Modi, newly elected prime minister, setting his lips to the steps leading into Parliament House. You might recall Narendra Modi, elected prime minister a second time, stooping to embrace the Constitution of India in the Central Hall of Parliament.

Those steps will soon not lead into the sanctum of what has also come to be known as the temple of our democracy; Parliament is in the process of changing shape and station. There will also no longer be a place called the Central Hall; it is being expunged from the architecture of the new republic in the making. Must our Constitution too now contemplate the consequences of being held demonstrably dear?

B.L. Santhosh, pre-eminent general-secretary of the BJP because he comes to the job as appointed RSS hand, may have offered a clue to anyone prepared to recognise it for what it was. Less than a fortnight ago, Santhosh tweeted:“June 18 PavagarhJuly 13 BaidyanathSep 1 KaladiOct 7 KulluOct 11 UjjainOct 21 Kedarnath, BadrinathOct 23 AyodhyaTemple visits of PM @narendramodi Cultural Renaissance happening with the involvement of the highest executive office of the land. Dhyanosmi…”

Santhosh’s message has an unmistakable ring to it — don’t tell us we didn’t tell you. This is New India as defined by the party in power. And as distinct from the Constitution that should be the scared text of its conduct. Celebrate the Hindu Hriday Samrat helming Hindu rashtra.

But the real thing about noticing Santhosh’s communique is this: it’s nothing new, it’s been happening a fair while, perhaps it is too late for it to stop happening. This is not an announcement, this is merely a happy assertion of ‘renaissance’ in full play.

Its formal act was probably what the nation witnessed from Ayodhya in August 2020 — the ritual merger of Church and State — rishi and raja — as Prime Minister Narendra Modi, elected head of a constitutionally secular State, turned de facto mahant to perform the ground-breaking rites of the Ram temple and declared all of India “Rammaya”, or suffused with Ram. Modi spoke with no ambiguity that in his imagination and his scheme, the Ayodhya event had finally embossed India as a Hindu country and him as its itinerant poster-boy.

The opening of a “new history”, Modi called it, an opening whose tone was consciously majoritarian and exclusionist of India’s pluralities. “This is an end to hundreds of years of waiting,” he proclaimed. “A day just like August 15 when we pronounce once again the end of our slavery. The trumpet of this victory is echoing across the world. My profuse congratulations to all bhakts and Ram bhakts. All of India, all of its 1.3 billion people, have become Ram-maya.” He spoke as if oblivious to, or defiant of, the truth that a fifth of India’s population, whom he also leads as prime minister, isn’t Hindu and Ram is not the deity of their denominations. Let that no longer matter, Modi’s demeanour as prime minister has insisted, and let nothing come in the way of the new order. If only as a tactile illustration of that, it would do to recall that nothing about the horror of Covid’s second wave impeded the mammoth recasting of Delhi’s Central Vista to the contours of the Modi republic.

What Modi began in 2013 — or what began with him and this nation that year — is only understood in part if it is understood as a quest for power. It was a quest for empire. We have seen two general elections since then, but what we may be missing out on is the referendum that was simultaneously triggered and has not come to the end of its course yet. It is a referendum that seeks to establish a majoritarian India. It is the quest for an empire that predates the many empires that ruled these parts over the last eight hundred years or so, empires fashioned by those that came from land, and empires fashioned by those that arrived via the seas. The little problem with those that arrived from land is that they stayed; they became part, and even when they parted, more stayed than went away. That problem needs solutions.

And so what was rolled out between the general elections of 2014 and 2019 was an undeclared, open-ended referendum on what the arrival of Narendra Modi in power should really come to mean. These were no ordinary elections. Their meaning needs to be understood beyond the numbers in the Lok Sabha and the arrangements of executive governments. The time that passed between the arrival of the first Modi government and the installation of the second also needs to be carefully grasped. This was no ordinary time. And the time to come may be even less ordinary. For if there is one thing the last two general elections have done, it is this: validate the values Modi and his worldview embody and vacate the values of several, or all, of his predecessors. Majoritarian India has never been so audaciously enthroned. The majoritarian ethic has never appeared so unflinching in its determination to impose itself. It has promised not to stop doing so, and is in a daily dare to those who will come in the way. It is thus that a sectarian sword becomes the essential arbiter of the law, let us not even speak of justice. It is thus that a call to murder becomes a patriotic act coming from some. It is thus that the cry of inquilab, the commonest cry of the agitating street, becomes an act of sedition coming from some. It is thus that a communal lynching amidst holy rites on a river ghat becomes barely a thing anybody notices. There’s more in the works where that came from. Far too much to convince ourselves that we haven’t already kissed the once-upon-a-time India goodbye.

sankarshan.thakur@abp.in