I experience feelings of uniqueness, radicalism, and pain while reading the writings of modern Indian national leaders, especially those recalling India’s past. No other nation has revisited its history to aid its fight against colonialism.

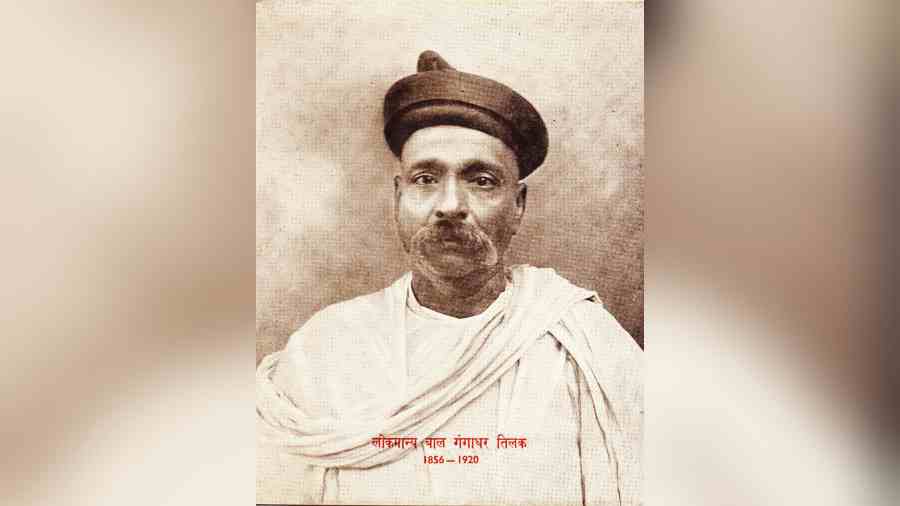

While recalling the past can lead to orthodoxy, this was only partially true in the case of India. Despite turning towards the past, the Indian leaders did not accept it passively. They made radical revisions, as seen in Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s interpretation of the Bhagavad Gita.

Tilak rejects the interpretations of the Gita originating from Adi Sankaracharya and subsequently extended by the other acharyas — including Ramanuja, Madhava, Nimbarka and Vallabha — that emphasised bhakti and the otherworld. These commentators on the Gita, Tilak alleges, “declared the path of Action (Karma-Yoga) preached by the Gita to be inferior”. Their interpretation reduced action to a mere instrument of bhakti and undermined the importance of this world. This is as symbolic as Raphael’s famous painting, School of Athens, in which Aristotle points toward the material reality in front of us in contrast to Plato pointing his finger upward. Similarly, Tilak is turning the gaze away from the transcendent god and bhakti and pointing towards this world and the actions surrounding it. While Aristotle proposes new philosophy, Tilak turns to the past for justification.

This is perhaps the first time that the Gita is discussed with reference not only to the classical schools of Indian philosophy but also to various ideas, comparisons, and differences in Western philosophy. The range of Western and Indian philosophers discussed in the text is extensive, scholarly, and trend-setting.

Tilak, in this context, makes two important points: one about the text and interpretation, and the other about the immediate context of his time. About the first, Tilak alleges that the interpretation by the acharyas belongs to the gunavada and does not reflect the text. This is a reference to the Mimamsa school of philosophy, where interpretation or Arthavada has three parts: anuvada, where interpretation is consistent with the text interpreted; if inconsistent, it is called gunavada; and, finally, if it is neither, it is called bhutharthavada.

The hermeneutic tradition in the West, too, rejects the concept of anuvada in the Mimamsa sense and considers all interpretations as gunavada. In contrast, Tilak seeks to restore the anuvada of the Gita by disclosing the rahasya or the secret of the Gita — the Karma-Yoga-Sastra, thus saving the text from relapsing into gunavada. He again refers to Mimamsa that says, “In ascertaining the meaning (of the texts or their corpus, individual sections, or topic), the characteristic signs are — (agreement between) the beginning [Upakrama] and the conclusion [Upasamhara], repetition, originality, result, eulogy, and reasoning.”

According to Tilak, the Gita begins with a confused Arjuna reluctant to participate in the Kurukshetra war. Krishna advises Arjuna and convinces him to fight the war. The beginning, therefore, is a state of inaction, while the end is the state of action. This, to Tilak, is the main message that Krishna tries to convey in the Gita — to do action and not turn away from one’s duty. This layered engagement with the past is more complex than the mere rejection of tradition.

Two, the compelling reason for Tilak to take this radical task is not merely of scholarly interest. He undertakes this arduous task against the background of awakening the Indians, enslaved to the British, to fight for independence. The political urgency is the context for the academic exercise. He holds the interpretations by acharyas that are not consistent with the Gita directly responsible for shaping Indian society and its people, especially in making them physically weak. He finds parallels between the psychological state of Arjuna before the war, especially his unwillingness to fight in the war, and the people of India under British rule. He deploys the Gita to motivate the ordinary people of India to fight against the British and achieve freedom.

Despite being unique and radical, it is painful to find that this foundational text of the Indian national movement is grossly neglected and ignored. This vital text does not find a place in the books on Indian Political Theory or Contemporary Indian Philosophy. Tilak wrote this massive work in Marathi while in Mandalay jail during 1910-1911, thus converting punishment into creativity that serves the national interest. I think there’s a need to revisit these texts irrespective of one’s agreement or otherwise with the author. Examining the descriptions in the text should precede the agreements and the disagreements.

Our national leaders were politically active and wrote extensively. However, present-day politicians interested in these national leaders are not trained in handling their writings. And their understanding without reading their texts will be found wanting. Academicians capable of handling them did not turn toward them as much as they could have. This creates a severe and irreparable gap in their understanding of India and its freedom struggle. Further, this makes it difficult for them to capture the uniqueness of modern India. Additionally, this does not enable them to understand some of the vulnerabilities of this uniqueness.

Revisiting these texts can let us know how leaders like Tilak actively negotiated the modern requirements of the importance of action and of this world seriously while dealing with traditional scholarship. We can learn from Tilak how to disagree with giants to resolve urgent contemporary problems — in his case, India’s freedom — and reinforce disagreement with evidence.

A. Raghuramaraju teaches Philosophy at the Indian Institute of Technology Tirupati